Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

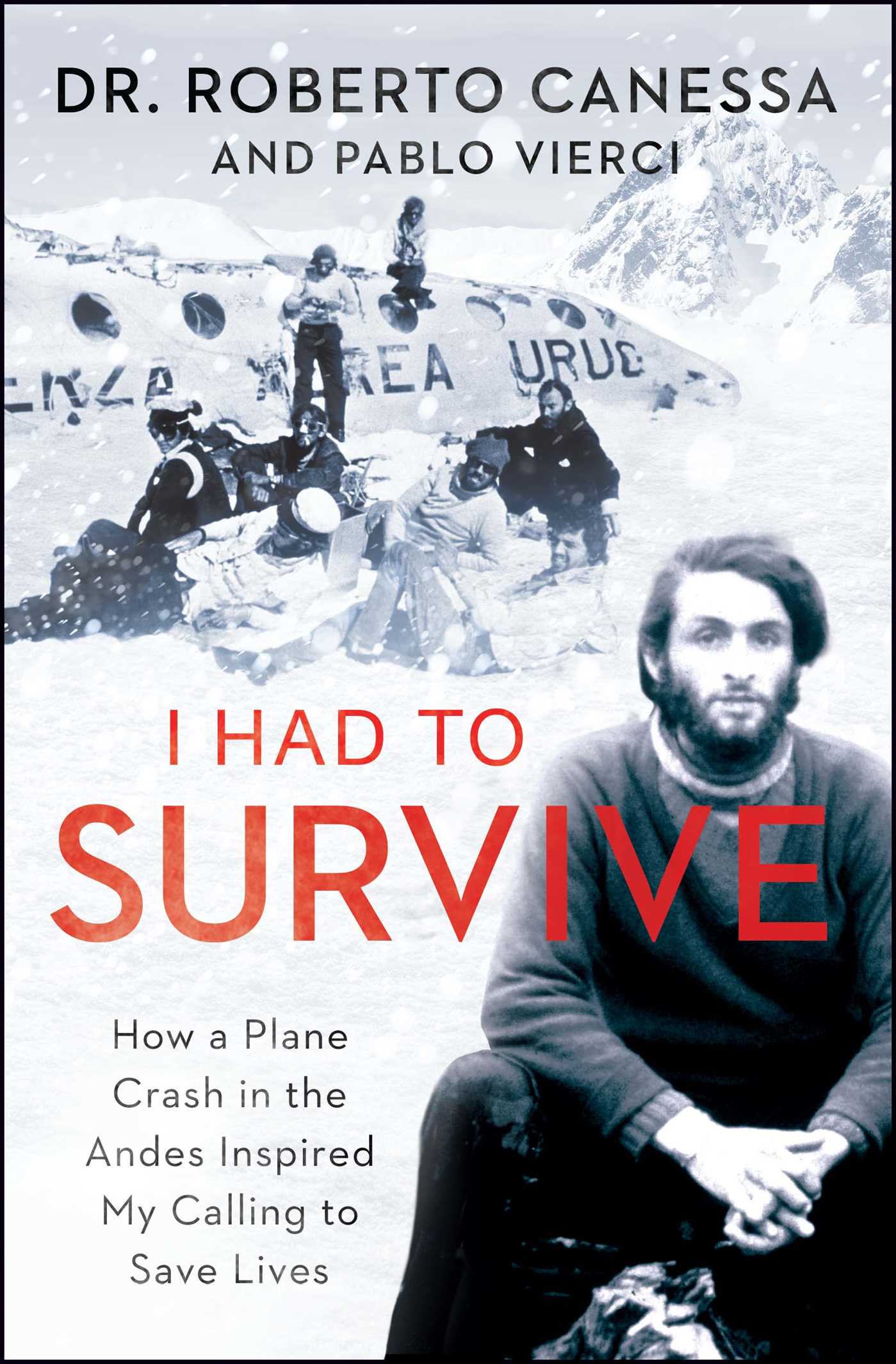

I Had to Survive

How a Plane Crash in the Andes Inspired My Calling to Save Lives

Table of Contents

About The Book

As he tended to his wounded Old Christians teammates amidst the devastating carnage, rugby player Roberto Canessa, a second-year medical student at the time, realized that no one on earth was luckier: he was alive—and for that, he should be eternally grateful. As the starving group struggled beyond the limits of what seemed possible, Canessa played a key role in safeguarding his fellow survivors, eventually trekking with a companion across the hostile mountain range for help.

No one could have imagined that there were survivors from the accident in such extreme conditions. Canessa's extraordinary experience on the fine line between life and death became the catalyst for the rest of his life.

This uplifting tale of hope and determination, solidarity and ingenuity, gives vivid insight into the world-famous story that inspired the movie Alive! Canessa also draws a unique and fascinating parallel between his work as a doctor diagnosing very complex congenital cardiopathies in unborn and newborn infants and the difficult life-changing decisions he was forced to make in the Andes. With grace and humanity, Canessa prompts us to ask ourselves: what do you do when all the odds are stacked against you?

Excerpt

Where is the line between life and death?

Through the screen of an ultrasound machine, I study the heart of a child about to be born. I take my time, watching the tiny hands and feet on the monitor, feeling as if we’re communicating somehow through the screen. I’m fascinated at this life that will soon be among us—and at this heart that will have to be repaired in order for the child to survive.

One moment I’m gazing at the ultrasound screen, and the next I’m staring out the window of the crumpled fuselage of a plane, scanning the horizon to see if my friends will return alive from their test hikes. Ever since we escaped from the plane crash in the Andes mountains on December 22, 1972, after being lost for more than two months, I have asked myself a litany of questions, which is constantly changing. Foremost among them: What do you do when all the odds seem stacked against you?

I turn to the pregnant mother, who is lying on a gurney on the second floor of the Hospital Italiano in Montevideo, Uruguay. What is the best way to tell her that the child in her womb has developed in utero lacking the most important chamber of her heart? Until just a few years ago, newborns with these kinds of congenital heart defects, who came into the world stricken through no fault of their own, would die shortly after birth. Their only mark on the world would be a brief agony followed by a lasting trauma for their families. Fortunately, however, medicine took a crucial step forward, and this mother, Azucena, with the look of consternation on her face, can now have hope. There is a long, arduous journey ahead for this woman and her baby daughter, as well as for her husband and their two other children. It is an uncharted path as precarious as the one I made through the Andes. My friends and I were lucky enough to emerge from those mountains finally and reach the verdant valley of Los Maitenes. That’s where I’m trying to lead these children, into their own verdant valley, although I carry the burden of knowing that not all of them will survive the journey.

This is my dilemma as a doctor. I find myself teetering between life and death as I watch this baby, whose mother has already named her Maria del Rosario. She can live for now, tethered to the placenta in her mother’s womb, but what is to be done afterward? Should I propose a series of long, drawn-out surgeries so that she has a chance at living? And will it be worth all the risks and costs involved? I’m sometimes overwhelmed at the similarities between our predicaments.

When we finally left the fuselage to trek across the peaks and chasms leading to that valley in Chile, we encountered a vast no-man’s-land. It’s almost impossible to remain alive in that weather, at thirty below, without any gear and after having lost nearly seventy pounds. It was impossible, everyone assumed, to trek more than fifty miles from east to west directly over the Andes, because no one in our weakened physical state would be able to withstand the rigors. We could have chosen to remain in that uterine fuselage, safe, until it, too, became inhospitable when we ran out of the only nourishment that was keeping us alive, the lifeless bodies of our friends. Just as the infant gets nourishment from the mother, we were able to do so from our friends, the most precious thing we had in that world. Should we stay or should we go? Remain huddled or press forward? The only equipment we had to help us on our journey was a sleeping bag we cobbled together out of insulation from the pipes of the plane’s heating system, stitched with copper wire. It looked like something plucked from a landfill.

This child, still a fetus, still connected to her source of nourishment, can survive a little longer, just as we did in the fuselage. But one day, as with us, the cord will have to be cut if she is to live, because we are in a race against time. I was the last one to decide to venture out, and that’s why this recurring image has remained with me, intense and haunting. When should we cut the cord? When should we subject ourselves to the ordeal of attempting to cross the hostile mountain range? I knew that a hasty decision to trek across the mountains carried great risk, just as premature labor does for these children with congenital heart defects.

It took me a lot of deliberation to make my choice. There were simply too many factors, but I knew we were down to our last chance. Nando Parrado understood my doubts because he was wary as well, although he couldn’t say this out loud for fear of letting down the rest of the survivors of the plane crash. With each person who died, we all died a little bit, too. It wasn’t until Gustavo Zerbino told me that one of the bravest of our friends, Numa Turcatti, had died, that I decided it was time to go. It was time to leave the safety of the fuselage, to be born with a heart that wasn’t ready for the outside world. One of my friends, Arturo Nogueira, who’d had both of his legs broken in the crash and eventually perished, told me, “You’re so lucky, Roberto, that you can walk for the rest of us.” Otherwise he might have been the one here today, in my place.

I was nineteen years old, a second-year medical student, a rugby player, and Lauri Surraco was my girlfriend when our plane crashed into the mountain that October 13, 1972. Those seventy days on the mountain were literally a crash course in the medicine of catastrophes, of survival, where the spark for my vocation would become a roaring flame. It was the most brutal of laboratories, where we were the guinea pigs—and we all knew it. In that sinister proving ground, I gained a new perspective on medicine: To be healed meant simply to survive. Nothing I learned since could compare with that ignoble birth.

In the hospitals where I’ve worked, some of my colleagues have criticized me, behind my back and to my face, for being domineering, impetuous, for flouting the rules or going beyond what’s considered proper conduct—something my companions on the mountain accused me of at times as well. But patients don’t care about the social mores of a medical corporation; they come to a hospital and then go home, no longer subject to its rules. My ways are the ways of the mountains. Hard, implacable, steeled over the anvil of an unrelenting wilderness in which only one thing matters: the fight to stay alive.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (March 21, 2017)

- Length: 320 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476765457

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"A world-famous pediatric cardiologist tells how surviving a plane crash in the high Andes led to a lifelong commitment to helping children overcome congenital heart defects...Inspiring from beginning to end."

– Kirkus

"Canessa—who went on to became a world-renowned pediatric cardiologist at the Italian Hospital of Montevideo—now draws parallels between the life-altering decisions he made on the mountain and the hope he provides to desperate parents by performing lifesaving heart surgeries on newborn infants and fetuses in utero. In this inspirational book, he recounts in breathtaking detail his harrowing journey across a harsh, uninhabited region of the Andes with fellow crash survivor Fernando Parrado to find help...it makes for riveting reading."

– Publishers Weekly

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): I Had to Survive Trade Paperback 9781476765457

- Author Photo (jpg): Roberto Canessa Photograph © Roberto Canessa(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit