Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

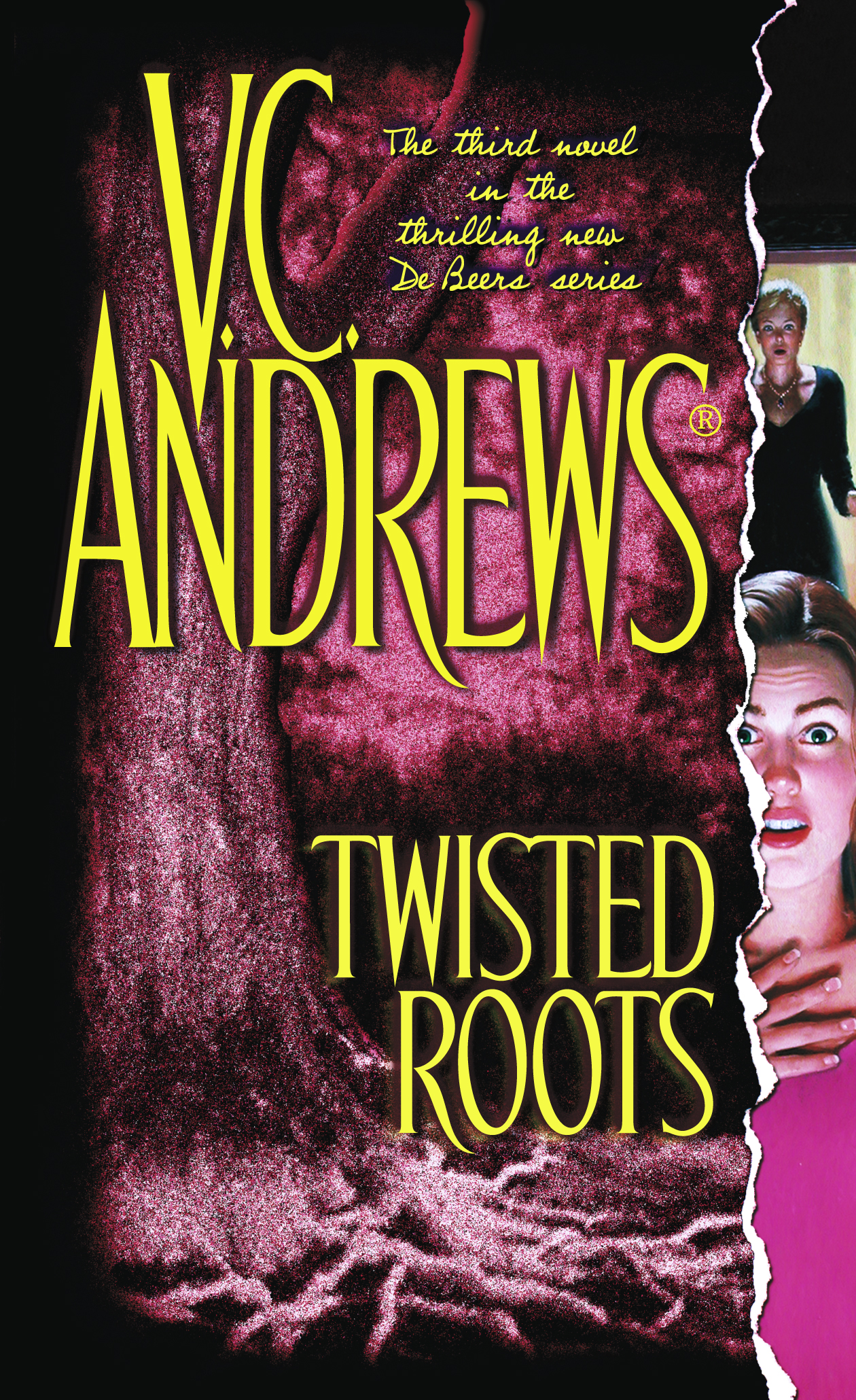

About The Book

The perfect family...and the perfect nightmare.

From the outside, Hannah Eaton seems to live a charmed life in wealthy Palm Beach, Florida, with her mother, Willow, a renowned psychologist, and her stepfather. But deep inside, she is miserable and lonely. She's been abandoned by her father, a pretentious lawyer whose family wants nothing to do with her. Now, the arrival of a new baby brother has consumed her mother, who is obsessed with caring for the sickly infant. And so, Hannah slips further into the shadows...

With the help of her boyfriend and her uncle, Hannah sets out for New Orleans to follow her dreams of singing. But life on the road holds many dark surprises—and shattering realities that Hannah herself may not be ready to face...

From the outside, Hannah Eaton seems to live a charmed life in wealthy Palm Beach, Florida, with her mother, Willow, a renowned psychologist, and her stepfather. But deep inside, she is miserable and lonely. She's been abandoned by her father, a pretentious lawyer whose family wants nothing to do with her. Now, the arrival of a new baby brother has consumed her mother, who is obsessed with caring for the sickly infant. And so, Hannah slips further into the shadows...

With the help of her boyfriend and her uncle, Hannah sets out for New Orleans to follow her dreams of singing. But life on the road holds many dark surprises—and shattering realities that Hannah herself may not be ready to face...

Excerpt

Chapter One

An Early Baby

I was too young to remember her before she died, but my mother had a nanny, who, according to the way Mommy talks about her, was more of a mother to her than certainly her stepmother was. Sometimes I think how weird it is that Grandmother Grace, Mommy, and I have each had at least one stepparent in our lives. Are some people meant to be brought up that way? I asked Mommy about that, and she said so many marriages end in divorces these days that it is not at all uncommon for a child to have stepparents.

"People marry and remarry the way teenagers used to go steady and break up to go steady with someone else years ago," she says. She's very bitter about it, although she would be the last one to admit to that. Psychologists, both she and Miguel remind me, are not supposed to be judgmental.

"We help our clients make those decisions on their own. We don't impose our values on them," she said.

However, I have heard her angrily remark many times that the marriage vows should be updated. "They should be rewritten to say, 'Do you take this woman to have and to hold -- for a while or until you get bored?' "

Sometimes she is so down on male-female relationships that I have to wonder if I will ever find anyone with whom I might be happy and spend the rest of my life. According to what he has told me and how he acts, my stepfather, Miguel, has no doubts about it. He seems to be very happy and very determined to spend the rest of his life with Mommy. I have never said anything to her about it, but I think he loves her more than she loves him. I know he makes her happy. He makes her laugh a lot, and I can see she enjoys her conversations with him, especially when they are discussing social and psychological topics. But sometimes, more often than ever, I think, she can be very distant. Her eyes take on a glazed look, and she stares at the sea or suddenly goes off to walk alone.

She steals away when Miguel or I least expect it, walking through the house on "pussy willow feet." I have watched her without her knowing, observed her on our beach, and have seen her moving slowly, as slowly as sand sifting through your fingers, idly watching time go by, her face sometimes taking on that dreamy far-off expression, her beautiful lips in a soft smile. It makes me think she hears voices no one else can hear, remembers a whisper, a touch, or even a kiss she has lost. Something wonderful slipped through her fingers years and years ago, perhaps, and now all she can do is resurrect the memory.

"All our memories are like bubbles, Hannah," she once told me. "They drift by and burst, and all you can do is wait for another chance to blow them through your thoughts so they can drift by again. Reach out to touch them, and they will pop and be gone. Sometimes I envy people who have suffered loss of memory and who are never tormented with their pasts. I even envy Linden, lost in some world of his own."

I hate it when she talks like that. It makes me think she would like to return to a time before I was born, as short as that happier period in her life might have been, and if she could, she would sell her soul to do so.

How can she be unhappy here? How could anyone? We live on an estate called Joya del Mar. We have an enormous main house with halls so long and rooms so large, you could bounce your echo along the walls. The property is vast, too. On it we have a beach house, our own private beach front, a magnificent pool, beautiful patios and walkways with enough flowers and bushes to fill a small public park. She doesn't have to do any household chores. We have a cook, Mrs. Haber, and a maid named Lila who has been with us nearly ten years. Twice a week a small army of grounds people manicure our property.

Professionally, Mommy is very successful. She has a psychotherapy practice with an office in West Palm Beach, not far from the magnet school I attend. Magnet schools provide a more specialized curriculum. Mine emphasizes the arts, and since I like to sing, Mother arranged for me to attend the A. W. Drefoos School of Arts in West Palm Beach. We get up and go together most of the time, or my stepfather takes me.

This was the year they were supposed to buy me my own car so I could drive myself places, but they have yet to do it. They have this idea that I should first find some sort of part-time job to at least pay for my own gas and insurance.

"When you accumulate enough to pay for at least one year's insurance, we'll get you the car," she has promised.

She also promised to help me by looking for a job that could fit into my schedule. I moaned and groaned, wondering aloud in front of them if my taking on a job wouldn't hurt my schoolwork. Miguel laughed.

"Oh, having a vehicle and driving all over the place won't cut in on your study time?"

I hate having parents who are so realistic. The parents of other girls my age accept at least a fantasy or two. However, it is very important to Mommy and Miguel that I develop a sense of value, the one sense they both insist is absent in Palm Beach.

"Here, people would think it justifiable to go to war over a jar of caviar," Mommy once quipped.

I do understand why she doesn't like the Palm Beach social world. My maternal grandmother Grace wasn't treated well here, and Mommy blames many of her own difficulties on that. At times Palm Beach doesn't seem real to me, either. It's too perfect. It glitters and feels like a movie set. When we cross the Flagler Bridge into West Palm Beach, Mother claims she is leaving the world of illusion and entering reality.

"Rich people here are richer than rich people most everywhere else," she told me. "Some of the wealthy people here are in fact wealthier than many small or third-world countries, Hannah. They keep reality outside their gold-plated walls. There are no cemeteries or hospitals in Palm Beach. Death and sickness have to stand outside the door. While the rest of us get stuck in traffic jams of all sorts in life, the wealthy residents of Palm Beach fly over them."

"What's wrong with that?" I asked her. "I'd like that."

"They haven't the tolerance for the slightest inconveniences anymore. Sometimes it's good to have a challenge, to be frustrated, to have to rise to an occasion, to find strength in yourself. You need some calluses on your soul, Hannah. You need to be stronger."

"But if you never run out of money and you can always buy away the frustrations, why would it matter?" I countered.

She looked at me very sternly.

"That's your father talking," she replied. Whenever she says that or says something like that, I feel as if she has just slapped me across the face.

"You'll see," she added. "Someday you'll see and you'll understand. I hope."

Should I hope the same thing? Why do we have to know about the ugly truths awaiting us? I wondered that aloud when I was with my stepfather once, and he said, "Because you appreciate the beauty more. I think what your mother is trying to get you to understand is that not only do these people she speaks of have a lower threshold of tolerance for the unpleasant things in life, but they have or develop a lower threshold of appreciation for the truly beautiful things as well. The Taj Mahal becomes, well, just another item on the list of places to visit and brag that you have seen, if you know what I mean."

I did, but for some reason, I didn't want to be so quick to say I did. Whenever Mommy or Miguel were critical of the Palm Beach social world, I understood they were being critical of my father and his family as well, and even though they weren't treating me like a member of that family, I couldn't help but think of them as part of me or me, part of them. I'm full of so many emotional contradictions, twisted and tangled like a telephone wire with all sorts of cross-communication. It's hard to explain to anyone who doesn't live a similar life so I keep it all bottled up inside me. I never tell anyone in my classes at school or any of my friends about these family conflicts and feelings.

Feelings, in fact, are often kept in little safes in our house. There is the sense that if we let too many of them out at the same time, we might explode. Everything is under control here. We're never too happy; we're never too sad. Whenever we approach either, there are techniques employed. After all, both Miguel and Mommy are experts in psychology.

Daddy is always urging me to be different from them, warning me that if I'm not, I'll be unhappy.

"Don't be like your mother," he says. "Don't analyze every pin drop. Forget about the whys and wherefors and enjoy. She's like a cook who can't go out to eat and take pleasure in something wonderful without first asking the waiter for a list of every ingredient and then questioning how it was prepared, always concluding with 'Oh, if he or she had done this or that, it would be even better.' Don't become like that, Hannah," he advises.

Maybe he's right.

But maybe, maybe I can't help it. After all, I am my mother's daughter, too, aren't I?

Or is my mother going to forget that I am her daughter? Is she hoping for that little loss of memory she often wishes she had?

I have another fear, a deep, dark suspicion that I remind her so much of my father that she can't tolerate it anymore and that was and is the real reason why she finally wanted another child, a child with Miguel.

Perhaps it is my imagination overworking or misinterpreting, but all throughout these last months of her pregnancy, I felt her growing more and more distant from me. She had less time to talk to me about my problems and concerns. Helping me find a suitable part-time job and getting me my own car seemed to have slipped out of both her and Miguel's minds. She had more concern for her practice, finding ways to continue to treat or have her clients treated while she was recuperating from giving birth than she had for me. She wanted to stop going to work the last month, and she was always very busy trying to make arrangements. I could see that even our morning ride together had changed. How many times did I say something or ask something and she didn't hear me because her ears were filled with her own worries and thoughts?

"What was that?" she would ask, or she would simply not respond and I would give up, close up like a clam, and stare out the window wishing I had woken with a cold and stayed home bundled up and forgotten.

However, my school, my teachers and some of the friends I had filled my life with more joy now. Staying home would have been punishing myself for no reason, or at least, no reason for which I could be blamed. In fact, some of my girlfriends actually felt sorry for me. They thought it would be weird if their mothers became pregnant like mine at this point in their family lives.

"I can tell you right now what's going to happen," Massy Hewlett declared with the authority of a Supreme Court judge. "You're going to end up being the family baby-sitter, and just when you should have more freedom to enjoy your social life."

"No," I told her. "They have already decided to hire a nanny. My mother had one when she was little. She didn't need one when I was born because she wasn't working yet, but she has to get back to her clients, so it's different now."

"It's not the same thing," Massy insisted. "You'll see. Older mothers are more neurotic. They have less tolerance, and they tend to exaggerate every little thing the baby does. A sneeze will become pneumonia."

"Don't you think Hannah's mother would be aware of all that?" Stacy Kreskin piped up. "She just happens to be a psychologist, Massy. It's not going to be the same for Hannah."

"We'll see," Massy said, refusing to be challenged or corrected. To Massy, being right was more important than being a good friend. It never even occurred to her that she was making me unhappy. I don't think she would have cared anyway.

Reluctant to be defeated, she simply shifted to another level of criticism.

"Even if she doesn't find herself baby-sitting or being asked to hang around the house, she'll feel like she doesn't exist anymore. There's a new king or queen. It happened to me!" she cried, shaking her head at the looks of either skepticism or disapproval. "My baby sister is nearly eight years younger, so I should know, shouldn't I? I'm just trying to give her a heads-up about it."

Our little clump grew silent and then broke away like blocks that had lost their glue and exploded, sailing off in a variety of directions. I was left alone to ponder the way my world would change, feeling as if I was floundering on the border between childhood needs and adult responsibilities. Should I be whining about the way our lives were changing or should I accept and adjust?

Maybe I shouldn't care. Maybe I should be happy. I'll be more on my own. I won't be on everyone's emotional radar screen. It's good to be ignored, isn't it? Or will I feel more unloved and unwanted than ever?

The conflict in me kept me so distracted, I felt like I was lost and drifting most of the time. Sometimes I felt I had stepped into the quagmire of emotions. I had to face it and find a way out. Now, with Mommy's water breaking and little Claude on the threshold of our home and family, there was no more putting it off for later. Whether I liked it or not, whether I was ready or not, the whole situation was in my face. It was all happening and it couldn't be ignored.

There was going to be another child in this house, a little prince.

The princess would have to step aside.

On those rare occasions when either Mommy or Miguel were unable to drive me to school, our head grounds keeper, Ricardo, drove me in his pickup truck. Unfortunately for me, these occasions were so rare, I couldn't use them as an excuse or reason for them to get me my own car before I had a suitable job or earned the year's worth of insurance.

"What good is my driver's license?" I whined more than ever lately. "I don't get much of an opportunity to use it. It's not safe for someone to drive as little as I do."

"Now, there's a good one," Miguel teased. "In order to make the highways safer, we should increase the number of teenagers with their own cars."

"I'm sure we'll make it all happen soon," Mommy promised. "As soon as I get free of these other issues, I'll help you find suitable employment, and Miguel will look into what car we should get for you. Soon," she repeated.

Soon: That was an easy word to hate. Adults, especially parents, used it as a shield to ward off requests and complaints. It was full of promise, but vague enough to keep them from having to make a real commitment.

Even rarer were times when Mommy's car was there for me to use. Right up to the last week of her pregnancy, she wanted her car at the house. It made her nervous not to have it available for an emergency. Ricardo could drive her anywhere if Miguel wasn't home, or even I could.

The morning Mommy's water broke, Miguel asked me if I would rather go with them to the hospital and wait for my baby brother to be born, but I told him I couldn't. I had an important English exam to take. I didn't, but I didn't want to be at the hospital. From simply listening to conversations Mommy and Miguel had about different clients of Mommy's, I knew enough to describe myself as being in denial. I resented little Claude so much I refused to admit to his coming and being. I actually imagined Mommy returning from the hospital without him and Miguel explaining it had all been an incorrect diagnosis. It had turned out to be a digestive problem easily corrected. There was no little Claude after all. Our lives, mine in particular, would not change. My world would no longer be topsy-turvy.

"Well, all right," Miguel said with disappointment flooding his face. "I'll tell you what," he said. "Let Ricardo drive you this morning, and I'll come to the school to get you if your mother gives birth before the day is over. I think that just might happen even though it's nearly a month too soon," he added with some trepidation in his voice.

"You could call the school and let them know to tell me, and I'll drive to the hospital," I said. "Just in case she doesn't give birth that quickly."

Once again his eyes darkened with disappointment.

"Your mother is nervous, Hannah. I don't want her worrying about you at this time," added.

"Why should she worry? I'm a good driver."

He stared without replying. It was his way of pleading for understanding.

"All right," I said petulantly. Little Claude hadn't made his first cry and already he was causing me unhappiness. I had to swallow it down.

"Thank you," Miguel said.

After they had left and I had my breakfast, I got into Ricardo's pickup truck.

"Today you become a sister," he declared with a joyful smile. "I bet you are excited, eh?"

"Yes," I lied. I didn't like airing my inner feelings, especially ones that had me feeling guilty and ashamed. I hated myself for that, but I hated what had made me that way even more.

Ricardo started to talk about his younger brothers and sisters. He was the oldest in a family of seven, but all of them had been born relatively close to each other. They all had much more in common than I would have with little Claude. By the time he was old enough to talk to me and understand anything significant, I would be in college. How could I ever think of him as a brother or ever care?

Ricardo's voice droned on. Even with its musical cadence and his happy tones, it became a monotonous stream of noise behind me, behind my dark and dreary thoughts.

"You can go a little faster, Ricardo," I interrupted. "I don't want to be late for school."

"Si, si," he said.

As we rode on, I glanced occasionally at pedestrians and the scenery, but I really saw no one or nothing, and when I arrived at school, I was surprised. Somehow, I didn't even realize the trip. I had been in too much of a daze. I hopped out quickly and barely uttered a thank-you and goodbye.

Not one of my friends seemed to notice how unhappy I was. It caused me to wonder if to them I always appeared this sad and depressed. Everyone seemed to be used to my silence, my dark eyes, my downward gaze and lack of energy. They rambled on with their usual excitement, swirling around me, showing off new clothing, new makeup, different hairdos, and passing on stories and rumors about this boy and that. I almost felt as if I had woven a cocoon about myself and none of them could see, hear, or touch me.

There was finally a reaction to and an awareness of my existence when Mrs. Margolis, the principal's assistant and secretary, appeared at my classroom door and announced I was to be excused.

"For a happy occasion," she added, unable to contain the news.

All my friends knew what that meant, and all turned to me, Massy's face a scowl of pity. I quickly gathered my books and hurried out, head down, my heart feeling more like it was growling than beating.

"Your stepfather is waiting for you in the lobby," Mrs. Margolis said as we walked down the hallway. "Congratulations," she added, and I muttered a thank-you and hurried along.

Miguel stood smiling proudly near the front entrance.

"I told you it would happen quickly. Little Claude has arrived," he announced.

"How's Mommy?" I asked.

"She's doing fine, but..." he added letting the but hang for a while as we walked out and to his car.

"But what?"

"Your little brother is smaller than we had expected him to be because he's technically a premature baby even though he weighs enough. He's doing fine, but to be on the safe side, the doctor would like to keep him there a little longer than they usually keep newborns."

"Oh," I said, caught in a rainstorm of different feelings and thoughts. A part of me hoped he stayed there forever, but a larger part of me felt very sad for Mommy and for Miguel.

"Naturally, your mother is concerned, so I thought it would be very good for you to visit, see little Claude, and tell her how beautiful he is," Miguel said. "I'm sure you understand," he added.

I nodded, but I also always believed Mommy could tell if I was not sincere about something. Even my father believed she had a second set of eyes that slipped in front of her regular eyes and pierced through any mask of deception.

"She ought to work for the CIA," he quipped on more than one occasion.

When we arrived at the hospital, we did as Miguel wanted and went to see little Claude first. He was in a bassinet that looked like it was built for a baby ten times his size. I couldn't believe how small he was and that this tiny creature in that miniature form was a full human being related to me. His head looked no bigger than an apple, and his hands and feet were so doll-like, I couldn't help doubting he was real. He was crying with such intensity, his face was actually the hue of a ripe apple. Despite his being only hours old, his skin around his tiny wrists and even under his eyes and his neck resembled skin wrinkled with age. I saw nothing beautiful about him and was actually happy about that. How could they make such a fuss over something like him?

"Isn't he remarkable?" Miguel asked, standing beside me and looking through the window.

"Yes," I said. "But you're right...he's so tiny."

"But he'll grow fast. In a few weeks you won't believe you're looking at the same child," he assured me. "He has my hair, although not much of it yet, huh?"

"Dipped in ink," I said, and Miguel laughed. When I was little, it was something he used to tell me about his hair and his beard.

"Right, right. Well, let's go see your mother," he said, and I followed him to her room.

Maybe I had a second set of eyes, too, because it only took one glimpse of her to know she was wading about in a pool of worry.

"Did you see him?" she asked almost before I stepped through the door.

"Yes. He's so tiny, but he has Miguel's hair," I said quickly. Miguel laughed, but Mommy held her expression of deep concern.

"I did everything I was supposed to do. I ate right. I don't smoke, and I didn't even have a glass of wine for nearly nine months. Those vitamins," she told Miguel, "we should have them analyzed. Vitamins and health foods are not inspected and analyzed by the government. Maybe they weren't what they were advertised to be."

"It's not the vitamins," Miguel said softly, closing and opening his eyes. "It makes no sense to flail about searching for some demon, Willow. You gave birth and that's it. He'll be fine. The doctor assures us."

She raised her eyebrows and looked at him with the face I knew my real father hated, the face that made a liar, a dreamer, a procrastinator swallow back his or her words. Miguel called her "lie-proof."

"Fibs and exaggerations bounce off and come back at the people who send them in her direction," Miguel told me often, leading me to think he was trying to warn me never to attempt to deceive her.

He raised his arms. "What?" he cried.

"They don't keep a baby as long as he wants to keep Claude under observation, Miguel. Too early is too early. Please. You're not talking to an idiot."

"All right, all right. Still, it will be fine. You will see."

"I hope so," she said and turned to me and finally smiled. "He is beautiful, though, isn't he, Hannah?"

"Uh-huh," I said even though my idea of a beautiful baby were the babies I saw in television commercials.

"You finally have a little brother. When I was growing up, I longed so for a sister or a brother. Most of my friends had one or the other, and even though they were always teasing or arguing with each other, I knew they at least had someone, had family. I'm sorry we waited so long to give you a sibling, honey. But you will be older and wiser and almost a second mother to him."

"When he's my age, I'll be thirty-four," I said. "I'll probably have my own children by then."

"Yes," she said. "But he will love having nieces and nephews, too. You'll see. If I've learned anything from marrying Miguel, it's how important and wonderful family can be. You'll see," she promised.

"I was thinking I would run back to the college and attend that faculty union meeting. It's important," Miguel said. "I should only be an hour or so."

"It's fine, Miguel. Hannah can stay a while with me."

"You're not tired?"

"I'll doze on and off, I imagine, but I wouldn't mind the company, if you wouldn't mind staying a while, Hannah."

"No, I want to stay," I said quickly.

"Fine, then," Miguel said. He walked to the door, turned, and raised his shoulders and puffed out his proud father's chest. "I'll be back," he added, pretending to be Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Both Mother and I laughed at his poor imitation, and then he left.

"Are you going to have Miguel bring Uncle Linden here to see him?" I asked her.

"No. I think it would be better if we just waited until we bring Claude home. Then we'll either have Linden over or take the baby there."

"Why? He can come out and go places," I said sharply. "We take him to restaurants, don't we? Why can't we bring him to a maternity ward?"

She scrunched her nose like she had just sipped some sour milk.

"I don't think it's a good idea to bring him to hospitals of any kind, Hannah. He doesn't feel good about that. Too many unhappy and unpleasant memories from his time in clinics and such. Why do that to him?" she asked.

"We leave him out of too many things," I complained.

She smiled. "He's not being left out."

"Yes, he is," I insisted.

"No one stands up for Linden like you do, Hannah. That's very nice."

"He doesn't have anyone but us," I said. "He's not related to Miguel and you're very busy. He's always saying you don't visit him as much as you used to visit him."

She shook her head. "He doesn't remember when I do."

"Yes, he does," I insisted.

"All right, honey, all right. Don't get yourself so upset about it. We won't leave Uncle Linden out of anything. I promise."

"I don't know why he's still in that place. He paints beautiful things. People buy them! He doesn't bother anyone. Why don't we just have him come home and live with us? Our house is certainly big enough, even with a new baby. We have rooms that have been shut up for as long as I can remember."

"He does well where he is, Hannah. Everything is organized for him, and he doesn't have to be reminded of bad memories, memories that made him sick."

"You have said that often before, Mommy, but I still don't understand what that means. What bad memories? What's in our house that would remind him of them anyway?"

She closed her eyes and let her head sink back on the pillow. The nurse came in to check her blood pressure and see how she was doing. Mommy introduced me to her, and I could see by the expression on her face that she was surprised my mother had a child as old as I was. Anyone looking at the two of us could see that I was really her daughter, too. She hadn't married Miguel and inherited me. We had the same nose and mouth. My eyes were my father's blue, but my hair was Mommy's light brunette shade. I had a slightly darker complexion. I was about an inch or so taller than she was, and I had a fuller figure. Some of my girlfriends were jealous of that, but I always wished I was more diminutive even though they thought I would be more attractive to most boys.

I've had boyfriends on and off since the ninth grade, but no one I would drool over or suffer heartbreak over when we went our separate ways, no one until this year. His name was Heyden Reynolds, and he was a new student in our school and very much a loner. Massy said he was weird and blamed it on his having a mother whose family came from Haiti and a father who was white and from New Orleans. His father was a musician with a jazz band and traveled a great deal. He had a fourteen-year-old sister, Elisha, who attended a regular public school, but being he was a talented songwriter and guitar player, Heyden came to our magnet school when he moved to West Palm Beach. He came every day on an old moped that other students teased him about, but he didn't seem to care.

I had spoken to him only a few times, but I sang with him once in vocal class, and the way he looked at me afterward made me tingle inside. I thought he was handsome with his caramel complexion and his dark, curly hair, strong mouth, and black pearl eyes. He was lean and tall like Miguel. I didn't find him weird because of his standoffish manner. I found him mysterious and a lot more interesting than the other boys in the school.

As soon as the nurse left Mommy's room, Mommy turned back to me. I didn't think she was going to say anything more about Uncle Linden. She never liked to talk about him all that much, especially with me, but she surprised me.

"Your uncle Linden has a hate-love relationship with Joya del Mar, Hannah. When you were little, we brought him around often, but he literally trembled as we drove through the gates each and every time."

"Why?" I asked, intrigued. She had never told me anything like this.

"You know he and my mother used to live in the beach house after my mother's stepfather practically bankrupted my grandmother Jackie Lee. It was difficult and sad for Linden to be forced to move out of his home and live in an apartment under the help's quarters. It made him bitter and he resented the Eatons."

"But you brought them back to the main house and paid off the debts. You fixed everything," I said.

She started to smile and stopped.

"Fixed," she said as if it pained her tongue. "Hardly that, Hannah. It was true that thanks to my father, I had inherited enough money and property to bail out my mother and Linden from their debts and make it possible for all of us to return to the main house, but I was also a foolish, impressionable young girl who allowed your father to charm and beguile me with his elegance and his promises. Even with your uncle Linden's mental turmoil and difficulties, he was wiser about your father than I was. I should have listened to him."

"If he was so wise and you were becoming a psychologist, why did he end up in a mental clinic?"

She took a deep breath. Was I being selfish by making her talk when she was tired and weak from giving birth? I couldn't help it. It was as if she were finally opening a door to a secret room, a room I had wanted to peer inside all my life.

"You know that his father, Kirby Scott, seduced and performed what amounted to rape of mine and Linden's mother. Linden had a very difficult and confused upbringing. For a while he was given to believe my grandmother was actually his mother. It was an attempt to sweep the disgrace under a rug. When he learned the truth about himself, it triggered his manic-depressive condition. He lived on the darkest edges of the world he envisioned. Right from the beginning Mother and he were not treated nicely by the people here. They made him feel freakish, and because of that, he became even more introverted.

"It became very serious after our mother died. He wanted to shut us both up and shut out the world outside our gates. He had something of a nervous breakdown over it, in fact. So you can see why our home is not the happiest of places for him to be, Hannah."

She smiled.

"You can see it in his art. The work he is doing at the residency is brighter, happier than the work he did here. Right?"

I nodded. "I wish, then, that we could sell Joya del Mar and find another place, one where he would be happier."

"I don't know if that would solve all his problems, honey," she said.

I sensed that there was more to see and know in this dark shut-up room, but she didn't look like she was going to tell it all to me.

"When I get married and move away, I'll make sure I have a home big enough for him, too," I vowed.

"Maybe you will," Mommy said smiling. She closed her eyes again. "Claude is beautiful," she muttered,

"isn't he, Hannah? I hope and pray he'll be all right. You pray, too, sweetheart, pray for your little brother."

I watched her drift off right in front of my eyes. Her breathing became soft and regular. For a few moments I sat there, pouting, and then I rose and went back to the nursery to look through the window at my new brother, at the little being who could bring so much joy to my mother and Miguel simply by appearing.

Looking at Claude caused me to wonder about Uncle Linden, born secretly in that beach house, barely knowing his mother before she was sent to my grandfather's clinic. Do babies sense the separation, long for their mothers without even realizing what it is that makes them feel so lost? Was Uncle Linden terrified at night when he cried and was comforted not by his mother, but by his grandmother?

Something made little Claude shudder, and then a moment later he waved his arms and small fists wildly, screaming. No one seemed to notice. I looked about frantically until finally I saw a nurse go to him. She held him for a moment, but that didn't stop his crying. His face looked even redder, and I thought, Do something before he chokes to death on his own tears.

I was about to pound on the glass and shout it, but the nurse smiled as if there was absolutely nothing wrong, then she said something to another nurse and took him out. I worried about where she had taken him until I saw she was bringing him to Mommy's room.

"What's wrong with him?" I asked.

"Nothing. He's just hungry," the nurse replied and went in to wake Mommy so she could breast-feed him. She had decided she would do that.

Nothing brought home little Claude's favored place and status in our family more than watching him suckle at Mommy's breast and seeing the angelic joy in her face. Mommy never told me whether or not she had breast-fed me, and suddenly it became very important to know.

"He's so hungry," Mommy said. "That's good."

"Was I breast-fed, too?" I asked abruptly.

Mommy looked up at me, holding her smile.

"No, actually, you weren't. I was so crazed back then. Your father and I had separated. I was feeling so abused. Despite what everyone was telling me, I couldn't help believing I had permitted him to ruin my life."

"Then you didn't want me to be born?"

"Yes, of course I did. I was just feeling terribly sorry for myself. My mother had died; Linden was not doing very well, as I explained to you, and here I was, pregnant with a husband who considered adultery less important than a parking ticket.

"But the moment you appeared on the scene, it all changed. It was as if the sun had finally come out on a rainy day."

"Then why didn't you breast-feed me, too?"

She hesitated, glanced at Claude, and then looked at me and forced a smile. Mommy's forced smiles always looked like she could go either way: cry or laugh.

"I just told you, Hannah. I was in somewhat of a state of turmoil. I had no one but Miguel really. I needed to get back on my feet as quickly as I could. I tried to stay home with you as long as I could, but eventually, I had to get out in the world and occupy myself. You had a wonderful nanny in Donna Castilla, and Mrs. Davis, bless her soul, watched over you as though you were her very own grandchild. In the beginning I had my hands full arbitrating the arguments between the two of them concerning what was best for you and what was not. Do you remember any of that?"

"A little," I said.

"Yes, well, I'm glad I didn't keep a nanny as long as my stepmother did, even though Amou was more my mother. You, thank goodness, had me and had a stepfather who has always loved you like his own."

"Now he has two children to love," I said.

She gazed down at Claude. I wondered if she could hear my fears in my voice. I really meant he'll love him more. It's only natural, I thought. Claude is his real child and Claude is his son.

"Does that hurt?" I asked.

"Breast-feeding? Just the opposite. However, you won't find many Palm Beach mothers doing it. They're terrified of losing their figures."

"Aren't you?"

"No," she said firmly. "Besides, I want to do what's best for him," she added.

Then why didn't you do what was best for me? I wanted to ask, but I didn't. I watched for a while, and then, after the nurse returned and took Claude back to the nursery, I went to get Mommy some magazines at the hospital gift shop. When I returned to the room, Miguel was there. He was ranting on and on about his faculty meeting, and Mommy was lying back on the pillow, a smile of amusement painted across her face.

"I mean, they will, they won't. Talk, talk, talk, but no action!" he exclaimed.

"They're afraid, Miguel. They have to talk themselves into it first. It takes time."

"Time is not something they have in abundance here, Willow. Oh, what's the use!" he cried and collapsed in the chair, his arms dangling. The he looked up at me and shook his head.

"Don't marry a schoolteacher unless he's independently wealthy," he told me.

"I'm not getting married," I retorted.

"What? Why not?"

"I want to have a career."

"Your mother has a career and she's married," he said, nodding at Mommy.

"She's different," I said. "She can be a psychologist and stay in one place. I will have to travel, do tours, be in shows. I won't have time for a husband and especially not for a child."

"Sure you will," Miguel said.

"No, I won't. I especially won't be able to breast-feed," I practically screamed.

The smile lifted off his face. He looked at Mommy.

"It's all right, Hannah. You're too young to have to worry about those things anyway," she said. "What did you get me?" she asked, and I brought her the magazines. "Good," she said, looking them over. "You guys better go home," she told Miguel.

"Sure," he said, standing. "I'll be back after dinner."

He leaned over and kissed her softly on the mouth.

"Thank you for my son," he whispered loud enough for me to hear.

She beamed.

I turned toward the door.

"Hannah?" she called, holding up her arms.

I went to her and let her embrace and kiss me on the cheek, but my own lips were still stuck in a firm pout.

"Take care of Miguel," she said. "Make sure he eats a real dinner and doesn't stop at some taco stand and call that a meal," she added, eyeing him with pretended fury.

He laughed. "She reads my mind, that woman. No wonder she is such a successful psychotherapist."

If she could only read mine, I thought, she would know how deep the hurt I felt was and how it seemed to travel through my body, even affecting the way I walked. Miguel insisted on stopping by the nursery on our way out.

"One more look to be sure it's all real," he said.

Little Claude was contentedly asleep, his tummy full of Mommy's milk. There was no umbilical cord between them, but he was still dependent on her.

He wasn't a day old, and he was already more a part of this family than I had ever been, I thought.

Maybe more than I would ever be.

Copyright © 2002 by the Vanda General Partnership

An Early Baby

I was too young to remember her before she died, but my mother had a nanny, who, according to the way Mommy talks about her, was more of a mother to her than certainly her stepmother was. Sometimes I think how weird it is that Grandmother Grace, Mommy, and I have each had at least one stepparent in our lives. Are some people meant to be brought up that way? I asked Mommy about that, and she said so many marriages end in divorces these days that it is not at all uncommon for a child to have stepparents.

"People marry and remarry the way teenagers used to go steady and break up to go steady with someone else years ago," she says. She's very bitter about it, although she would be the last one to admit to that. Psychologists, both she and Miguel remind me, are not supposed to be judgmental.

"We help our clients make those decisions on their own. We don't impose our values on them," she said.

However, I have heard her angrily remark many times that the marriage vows should be updated. "They should be rewritten to say, 'Do you take this woman to have and to hold -- for a while or until you get bored?' "

Sometimes she is so down on male-female relationships that I have to wonder if I will ever find anyone with whom I might be happy and spend the rest of my life. According to what he has told me and how he acts, my stepfather, Miguel, has no doubts about it. He seems to be very happy and very determined to spend the rest of his life with Mommy. I have never said anything to her about it, but I think he loves her more than she loves him. I know he makes her happy. He makes her laugh a lot, and I can see she enjoys her conversations with him, especially when they are discussing social and psychological topics. But sometimes, more often than ever, I think, she can be very distant. Her eyes take on a glazed look, and she stares at the sea or suddenly goes off to walk alone.

She steals away when Miguel or I least expect it, walking through the house on "pussy willow feet." I have watched her without her knowing, observed her on our beach, and have seen her moving slowly, as slowly as sand sifting through your fingers, idly watching time go by, her face sometimes taking on that dreamy far-off expression, her beautiful lips in a soft smile. It makes me think she hears voices no one else can hear, remembers a whisper, a touch, or even a kiss she has lost. Something wonderful slipped through her fingers years and years ago, perhaps, and now all she can do is resurrect the memory.

"All our memories are like bubbles, Hannah," she once told me. "They drift by and burst, and all you can do is wait for another chance to blow them through your thoughts so they can drift by again. Reach out to touch them, and they will pop and be gone. Sometimes I envy people who have suffered loss of memory and who are never tormented with their pasts. I even envy Linden, lost in some world of his own."

I hate it when she talks like that. It makes me think she would like to return to a time before I was born, as short as that happier period in her life might have been, and if she could, she would sell her soul to do so.

How can she be unhappy here? How could anyone? We live on an estate called Joya del Mar. We have an enormous main house with halls so long and rooms so large, you could bounce your echo along the walls. The property is vast, too. On it we have a beach house, our own private beach front, a magnificent pool, beautiful patios and walkways with enough flowers and bushes to fill a small public park. She doesn't have to do any household chores. We have a cook, Mrs. Haber, and a maid named Lila who has been with us nearly ten years. Twice a week a small army of grounds people manicure our property.

Professionally, Mommy is very successful. She has a psychotherapy practice with an office in West Palm Beach, not far from the magnet school I attend. Magnet schools provide a more specialized curriculum. Mine emphasizes the arts, and since I like to sing, Mother arranged for me to attend the A. W. Drefoos School of Arts in West Palm Beach. We get up and go together most of the time, or my stepfather takes me.

This was the year they were supposed to buy me my own car so I could drive myself places, but they have yet to do it. They have this idea that I should first find some sort of part-time job to at least pay for my own gas and insurance.

"When you accumulate enough to pay for at least one year's insurance, we'll get you the car," she has promised.

She also promised to help me by looking for a job that could fit into my schedule. I moaned and groaned, wondering aloud in front of them if my taking on a job wouldn't hurt my schoolwork. Miguel laughed.

"Oh, having a vehicle and driving all over the place won't cut in on your study time?"

I hate having parents who are so realistic. The parents of other girls my age accept at least a fantasy or two. However, it is very important to Mommy and Miguel that I develop a sense of value, the one sense they both insist is absent in Palm Beach.

"Here, people would think it justifiable to go to war over a jar of caviar," Mommy once quipped.

I do understand why she doesn't like the Palm Beach social world. My maternal grandmother Grace wasn't treated well here, and Mommy blames many of her own difficulties on that. At times Palm Beach doesn't seem real to me, either. It's too perfect. It glitters and feels like a movie set. When we cross the Flagler Bridge into West Palm Beach, Mother claims she is leaving the world of illusion and entering reality.

"Rich people here are richer than rich people most everywhere else," she told me. "Some of the wealthy people here are in fact wealthier than many small or third-world countries, Hannah. They keep reality outside their gold-plated walls. There are no cemeteries or hospitals in Palm Beach. Death and sickness have to stand outside the door. While the rest of us get stuck in traffic jams of all sorts in life, the wealthy residents of Palm Beach fly over them."

"What's wrong with that?" I asked her. "I'd like that."

"They haven't the tolerance for the slightest inconveniences anymore. Sometimes it's good to have a challenge, to be frustrated, to have to rise to an occasion, to find strength in yourself. You need some calluses on your soul, Hannah. You need to be stronger."

"But if you never run out of money and you can always buy away the frustrations, why would it matter?" I countered.

She looked at me very sternly.

"That's your father talking," she replied. Whenever she says that or says something like that, I feel as if she has just slapped me across the face.

"You'll see," she added. "Someday you'll see and you'll understand. I hope."

Should I hope the same thing? Why do we have to know about the ugly truths awaiting us? I wondered that aloud when I was with my stepfather once, and he said, "Because you appreciate the beauty more. I think what your mother is trying to get you to understand is that not only do these people she speaks of have a lower threshold of tolerance for the unpleasant things in life, but they have or develop a lower threshold of appreciation for the truly beautiful things as well. The Taj Mahal becomes, well, just another item on the list of places to visit and brag that you have seen, if you know what I mean."

I did, but for some reason, I didn't want to be so quick to say I did. Whenever Mommy or Miguel were critical of the Palm Beach social world, I understood they were being critical of my father and his family as well, and even though they weren't treating me like a member of that family, I couldn't help but think of them as part of me or me, part of them. I'm full of so many emotional contradictions, twisted and tangled like a telephone wire with all sorts of cross-communication. It's hard to explain to anyone who doesn't live a similar life so I keep it all bottled up inside me. I never tell anyone in my classes at school or any of my friends about these family conflicts and feelings.

Feelings, in fact, are often kept in little safes in our house. There is the sense that if we let too many of them out at the same time, we might explode. Everything is under control here. We're never too happy; we're never too sad. Whenever we approach either, there are techniques employed. After all, both Miguel and Mommy are experts in psychology.

Daddy is always urging me to be different from them, warning me that if I'm not, I'll be unhappy.

"Don't be like your mother," he says. "Don't analyze every pin drop. Forget about the whys and wherefors and enjoy. She's like a cook who can't go out to eat and take pleasure in something wonderful without first asking the waiter for a list of every ingredient and then questioning how it was prepared, always concluding with 'Oh, if he or she had done this or that, it would be even better.' Don't become like that, Hannah," he advises.

Maybe he's right.

But maybe, maybe I can't help it. After all, I am my mother's daughter, too, aren't I?

Or is my mother going to forget that I am her daughter? Is she hoping for that little loss of memory she often wishes she had?

I have another fear, a deep, dark suspicion that I remind her so much of my father that she can't tolerate it anymore and that was and is the real reason why she finally wanted another child, a child with Miguel.

Perhaps it is my imagination overworking or misinterpreting, but all throughout these last months of her pregnancy, I felt her growing more and more distant from me. She had less time to talk to me about my problems and concerns. Helping me find a suitable part-time job and getting me my own car seemed to have slipped out of both her and Miguel's minds. She had more concern for her practice, finding ways to continue to treat or have her clients treated while she was recuperating from giving birth than she had for me. She wanted to stop going to work the last month, and she was always very busy trying to make arrangements. I could see that even our morning ride together had changed. How many times did I say something or ask something and she didn't hear me because her ears were filled with her own worries and thoughts?

"What was that?" she would ask, or she would simply not respond and I would give up, close up like a clam, and stare out the window wishing I had woken with a cold and stayed home bundled up and forgotten.

However, my school, my teachers and some of the friends I had filled my life with more joy now. Staying home would have been punishing myself for no reason, or at least, no reason for which I could be blamed. In fact, some of my girlfriends actually felt sorry for me. They thought it would be weird if their mothers became pregnant like mine at this point in their family lives.

"I can tell you right now what's going to happen," Massy Hewlett declared with the authority of a Supreme Court judge. "You're going to end up being the family baby-sitter, and just when you should have more freedom to enjoy your social life."

"No," I told her. "They have already decided to hire a nanny. My mother had one when she was little. She didn't need one when I was born because she wasn't working yet, but she has to get back to her clients, so it's different now."

"It's not the same thing," Massy insisted. "You'll see. Older mothers are more neurotic. They have less tolerance, and they tend to exaggerate every little thing the baby does. A sneeze will become pneumonia."

"Don't you think Hannah's mother would be aware of all that?" Stacy Kreskin piped up. "She just happens to be a psychologist, Massy. It's not going to be the same for Hannah."

"We'll see," Massy said, refusing to be challenged or corrected. To Massy, being right was more important than being a good friend. It never even occurred to her that she was making me unhappy. I don't think she would have cared anyway.

Reluctant to be defeated, she simply shifted to another level of criticism.

"Even if she doesn't find herself baby-sitting or being asked to hang around the house, she'll feel like she doesn't exist anymore. There's a new king or queen. It happened to me!" she cried, shaking her head at the looks of either skepticism or disapproval. "My baby sister is nearly eight years younger, so I should know, shouldn't I? I'm just trying to give her a heads-up about it."

Our little clump grew silent and then broke away like blocks that had lost their glue and exploded, sailing off in a variety of directions. I was left alone to ponder the way my world would change, feeling as if I was floundering on the border between childhood needs and adult responsibilities. Should I be whining about the way our lives were changing or should I accept and adjust?

Maybe I shouldn't care. Maybe I should be happy. I'll be more on my own. I won't be on everyone's emotional radar screen. It's good to be ignored, isn't it? Or will I feel more unloved and unwanted than ever?

The conflict in me kept me so distracted, I felt like I was lost and drifting most of the time. Sometimes I felt I had stepped into the quagmire of emotions. I had to face it and find a way out. Now, with Mommy's water breaking and little Claude on the threshold of our home and family, there was no more putting it off for later. Whether I liked it or not, whether I was ready or not, the whole situation was in my face. It was all happening and it couldn't be ignored.

There was going to be another child in this house, a little prince.

The princess would have to step aside.

On those rare occasions when either Mommy or Miguel were unable to drive me to school, our head grounds keeper, Ricardo, drove me in his pickup truck. Unfortunately for me, these occasions were so rare, I couldn't use them as an excuse or reason for them to get me my own car before I had a suitable job or earned the year's worth of insurance.

"What good is my driver's license?" I whined more than ever lately. "I don't get much of an opportunity to use it. It's not safe for someone to drive as little as I do."

"Now, there's a good one," Miguel teased. "In order to make the highways safer, we should increase the number of teenagers with their own cars."

"I'm sure we'll make it all happen soon," Mommy promised. "As soon as I get free of these other issues, I'll help you find suitable employment, and Miguel will look into what car we should get for you. Soon," she repeated.

Soon: That was an easy word to hate. Adults, especially parents, used it as a shield to ward off requests and complaints. It was full of promise, but vague enough to keep them from having to make a real commitment.

Even rarer were times when Mommy's car was there for me to use. Right up to the last week of her pregnancy, she wanted her car at the house. It made her nervous not to have it available for an emergency. Ricardo could drive her anywhere if Miguel wasn't home, or even I could.

The morning Mommy's water broke, Miguel asked me if I would rather go with them to the hospital and wait for my baby brother to be born, but I told him I couldn't. I had an important English exam to take. I didn't, but I didn't want to be at the hospital. From simply listening to conversations Mommy and Miguel had about different clients of Mommy's, I knew enough to describe myself as being in denial. I resented little Claude so much I refused to admit to his coming and being. I actually imagined Mommy returning from the hospital without him and Miguel explaining it had all been an incorrect diagnosis. It had turned out to be a digestive problem easily corrected. There was no little Claude after all. Our lives, mine in particular, would not change. My world would no longer be topsy-turvy.

"Well, all right," Miguel said with disappointment flooding his face. "I'll tell you what," he said. "Let Ricardo drive you this morning, and I'll come to the school to get you if your mother gives birth before the day is over. I think that just might happen even though it's nearly a month too soon," he added with some trepidation in his voice.

"You could call the school and let them know to tell me, and I'll drive to the hospital," I said. "Just in case she doesn't give birth that quickly."

Once again his eyes darkened with disappointment.

"Your mother is nervous, Hannah. I don't want her worrying about you at this time," added.

"Why should she worry? I'm a good driver."

He stared without replying. It was his way of pleading for understanding.

"All right," I said petulantly. Little Claude hadn't made his first cry and already he was causing me unhappiness. I had to swallow it down.

"Thank you," Miguel said.

After they had left and I had my breakfast, I got into Ricardo's pickup truck.

"Today you become a sister," he declared with a joyful smile. "I bet you are excited, eh?"

"Yes," I lied. I didn't like airing my inner feelings, especially ones that had me feeling guilty and ashamed. I hated myself for that, but I hated what had made me that way even more.

Ricardo started to talk about his younger brothers and sisters. He was the oldest in a family of seven, but all of them had been born relatively close to each other. They all had much more in common than I would have with little Claude. By the time he was old enough to talk to me and understand anything significant, I would be in college. How could I ever think of him as a brother or ever care?

Ricardo's voice droned on. Even with its musical cadence and his happy tones, it became a monotonous stream of noise behind me, behind my dark and dreary thoughts.

"You can go a little faster, Ricardo," I interrupted. "I don't want to be late for school."

"Si, si," he said.

As we rode on, I glanced occasionally at pedestrians and the scenery, but I really saw no one or nothing, and when I arrived at school, I was surprised. Somehow, I didn't even realize the trip. I had been in too much of a daze. I hopped out quickly and barely uttered a thank-you and goodbye.

Not one of my friends seemed to notice how unhappy I was. It caused me to wonder if to them I always appeared this sad and depressed. Everyone seemed to be used to my silence, my dark eyes, my downward gaze and lack of energy. They rambled on with their usual excitement, swirling around me, showing off new clothing, new makeup, different hairdos, and passing on stories and rumors about this boy and that. I almost felt as if I had woven a cocoon about myself and none of them could see, hear, or touch me.

There was finally a reaction to and an awareness of my existence when Mrs. Margolis, the principal's assistant and secretary, appeared at my classroom door and announced I was to be excused.

"For a happy occasion," she added, unable to contain the news.

All my friends knew what that meant, and all turned to me, Massy's face a scowl of pity. I quickly gathered my books and hurried out, head down, my heart feeling more like it was growling than beating.

"Your stepfather is waiting for you in the lobby," Mrs. Margolis said as we walked down the hallway. "Congratulations," she added, and I muttered a thank-you and hurried along.

Miguel stood smiling proudly near the front entrance.

"I told you it would happen quickly. Little Claude has arrived," he announced.

"How's Mommy?" I asked.

"She's doing fine, but..." he added letting the but hang for a while as we walked out and to his car.

"But what?"

"Your little brother is smaller than we had expected him to be because he's technically a premature baby even though he weighs enough. He's doing fine, but to be on the safe side, the doctor would like to keep him there a little longer than they usually keep newborns."

"Oh," I said, caught in a rainstorm of different feelings and thoughts. A part of me hoped he stayed there forever, but a larger part of me felt very sad for Mommy and for Miguel.

"Naturally, your mother is concerned, so I thought it would be very good for you to visit, see little Claude, and tell her how beautiful he is," Miguel said. "I'm sure you understand," he added.

I nodded, but I also always believed Mommy could tell if I was not sincere about something. Even my father believed she had a second set of eyes that slipped in front of her regular eyes and pierced through any mask of deception.

"She ought to work for the CIA," he quipped on more than one occasion.

When we arrived at the hospital, we did as Miguel wanted and went to see little Claude first. He was in a bassinet that looked like it was built for a baby ten times his size. I couldn't believe how small he was and that this tiny creature in that miniature form was a full human being related to me. His head looked no bigger than an apple, and his hands and feet were so doll-like, I couldn't help doubting he was real. He was crying with such intensity, his face was actually the hue of a ripe apple. Despite his being only hours old, his skin around his tiny wrists and even under his eyes and his neck resembled skin wrinkled with age. I saw nothing beautiful about him and was actually happy about that. How could they make such a fuss over something like him?

"Isn't he remarkable?" Miguel asked, standing beside me and looking through the window.

"Yes," I said. "But you're right...he's so tiny."

"But he'll grow fast. In a few weeks you won't believe you're looking at the same child," he assured me. "He has my hair, although not much of it yet, huh?"

"Dipped in ink," I said, and Miguel laughed. When I was little, it was something he used to tell me about his hair and his beard.

"Right, right. Well, let's go see your mother," he said, and I followed him to her room.

Maybe I had a second set of eyes, too, because it only took one glimpse of her to know she was wading about in a pool of worry.

"Did you see him?" she asked almost before I stepped through the door.

"Yes. He's so tiny, but he has Miguel's hair," I said quickly. Miguel laughed, but Mommy held her expression of deep concern.

"I did everything I was supposed to do. I ate right. I don't smoke, and I didn't even have a glass of wine for nearly nine months. Those vitamins," she told Miguel, "we should have them analyzed. Vitamins and health foods are not inspected and analyzed by the government. Maybe they weren't what they were advertised to be."

"It's not the vitamins," Miguel said softly, closing and opening his eyes. "It makes no sense to flail about searching for some demon, Willow. You gave birth and that's it. He'll be fine. The doctor assures us."

She raised her eyebrows and looked at him with the face I knew my real father hated, the face that made a liar, a dreamer, a procrastinator swallow back his or her words. Miguel called her "lie-proof."

"Fibs and exaggerations bounce off and come back at the people who send them in her direction," Miguel told me often, leading me to think he was trying to warn me never to attempt to deceive her.

He raised his arms. "What?" he cried.

"They don't keep a baby as long as he wants to keep Claude under observation, Miguel. Too early is too early. Please. You're not talking to an idiot."

"All right, all right. Still, it will be fine. You will see."

"I hope so," she said and turned to me and finally smiled. "He is beautiful, though, isn't he, Hannah?"

"Uh-huh," I said even though my idea of a beautiful baby were the babies I saw in television commercials.

"You finally have a little brother. When I was growing up, I longed so for a sister or a brother. Most of my friends had one or the other, and even though they were always teasing or arguing with each other, I knew they at least had someone, had family. I'm sorry we waited so long to give you a sibling, honey. But you will be older and wiser and almost a second mother to him."

"When he's my age, I'll be thirty-four," I said. "I'll probably have my own children by then."

"Yes," she said. "But he will love having nieces and nephews, too. You'll see. If I've learned anything from marrying Miguel, it's how important and wonderful family can be. You'll see," she promised.

"I was thinking I would run back to the college and attend that faculty union meeting. It's important," Miguel said. "I should only be an hour or so."

"It's fine, Miguel. Hannah can stay a while with me."

"You're not tired?"

"I'll doze on and off, I imagine, but I wouldn't mind the company, if you wouldn't mind staying a while, Hannah."

"No, I want to stay," I said quickly.

"Fine, then," Miguel said. He walked to the door, turned, and raised his shoulders and puffed out his proud father's chest. "I'll be back," he added, pretending to be Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Both Mother and I laughed at his poor imitation, and then he left.

"Are you going to have Miguel bring Uncle Linden here to see him?" I asked her.

"No. I think it would be better if we just waited until we bring Claude home. Then we'll either have Linden over or take the baby there."

"Why? He can come out and go places," I said sharply. "We take him to restaurants, don't we? Why can't we bring him to a maternity ward?"

She scrunched her nose like she had just sipped some sour milk.

"I don't think it's a good idea to bring him to hospitals of any kind, Hannah. He doesn't feel good about that. Too many unhappy and unpleasant memories from his time in clinics and such. Why do that to him?" she asked.

"We leave him out of too many things," I complained.

She smiled. "He's not being left out."

"Yes, he is," I insisted.

"No one stands up for Linden like you do, Hannah. That's very nice."

"He doesn't have anyone but us," I said. "He's not related to Miguel and you're very busy. He's always saying you don't visit him as much as you used to visit him."

She shook her head. "He doesn't remember when I do."

"Yes, he does," I insisted.

"All right, honey, all right. Don't get yourself so upset about it. We won't leave Uncle Linden out of anything. I promise."

"I don't know why he's still in that place. He paints beautiful things. People buy them! He doesn't bother anyone. Why don't we just have him come home and live with us? Our house is certainly big enough, even with a new baby. We have rooms that have been shut up for as long as I can remember."

"He does well where he is, Hannah. Everything is organized for him, and he doesn't have to be reminded of bad memories, memories that made him sick."

"You have said that often before, Mommy, but I still don't understand what that means. What bad memories? What's in our house that would remind him of them anyway?"

She closed her eyes and let her head sink back on the pillow. The nurse came in to check her blood pressure and see how she was doing. Mommy introduced me to her, and I could see by the expression on her face that she was surprised my mother had a child as old as I was. Anyone looking at the two of us could see that I was really her daughter, too. She hadn't married Miguel and inherited me. We had the same nose and mouth. My eyes were my father's blue, but my hair was Mommy's light brunette shade. I had a slightly darker complexion. I was about an inch or so taller than she was, and I had a fuller figure. Some of my girlfriends were jealous of that, but I always wished I was more diminutive even though they thought I would be more attractive to most boys.

I've had boyfriends on and off since the ninth grade, but no one I would drool over or suffer heartbreak over when we went our separate ways, no one until this year. His name was Heyden Reynolds, and he was a new student in our school and very much a loner. Massy said he was weird and blamed it on his having a mother whose family came from Haiti and a father who was white and from New Orleans. His father was a musician with a jazz band and traveled a great deal. He had a fourteen-year-old sister, Elisha, who attended a regular public school, but being he was a talented songwriter and guitar player, Heyden came to our magnet school when he moved to West Palm Beach. He came every day on an old moped that other students teased him about, but he didn't seem to care.

I had spoken to him only a few times, but I sang with him once in vocal class, and the way he looked at me afterward made me tingle inside. I thought he was handsome with his caramel complexion and his dark, curly hair, strong mouth, and black pearl eyes. He was lean and tall like Miguel. I didn't find him weird because of his standoffish manner. I found him mysterious and a lot more interesting than the other boys in the school.

As soon as the nurse left Mommy's room, Mommy turned back to me. I didn't think she was going to say anything more about Uncle Linden. She never liked to talk about him all that much, especially with me, but she surprised me.

"Your uncle Linden has a hate-love relationship with Joya del Mar, Hannah. When you were little, we brought him around often, but he literally trembled as we drove through the gates each and every time."

"Why?" I asked, intrigued. She had never told me anything like this.

"You know he and my mother used to live in the beach house after my mother's stepfather practically bankrupted my grandmother Jackie Lee. It was difficult and sad for Linden to be forced to move out of his home and live in an apartment under the help's quarters. It made him bitter and he resented the Eatons."

"But you brought them back to the main house and paid off the debts. You fixed everything," I said.

She started to smile and stopped.

"Fixed," she said as if it pained her tongue. "Hardly that, Hannah. It was true that thanks to my father, I had inherited enough money and property to bail out my mother and Linden from their debts and make it possible for all of us to return to the main house, but I was also a foolish, impressionable young girl who allowed your father to charm and beguile me with his elegance and his promises. Even with your uncle Linden's mental turmoil and difficulties, he was wiser about your father than I was. I should have listened to him."

"If he was so wise and you were becoming a psychologist, why did he end up in a mental clinic?"

She took a deep breath. Was I being selfish by making her talk when she was tired and weak from giving birth? I couldn't help it. It was as if she were finally opening a door to a secret room, a room I had wanted to peer inside all my life.

"You know that his father, Kirby Scott, seduced and performed what amounted to rape of mine and Linden's mother. Linden had a very difficult and confused upbringing. For a while he was given to believe my grandmother was actually his mother. It was an attempt to sweep the disgrace under a rug. When he learned the truth about himself, it triggered his manic-depressive condition. He lived on the darkest edges of the world he envisioned. Right from the beginning Mother and he were not treated nicely by the people here. They made him feel freakish, and because of that, he became even more introverted.

"It became very serious after our mother died. He wanted to shut us both up and shut out the world outside our gates. He had something of a nervous breakdown over it, in fact. So you can see why our home is not the happiest of places for him to be, Hannah."

She smiled.

"You can see it in his art. The work he is doing at the residency is brighter, happier than the work he did here. Right?"

I nodded. "I wish, then, that we could sell Joya del Mar and find another place, one where he would be happier."

"I don't know if that would solve all his problems, honey," she said.

I sensed that there was more to see and know in this dark shut-up room, but she didn't look like she was going to tell it all to me.

"When I get married and move away, I'll make sure I have a home big enough for him, too," I vowed.

"Maybe you will," Mommy said smiling. She closed her eyes again. "Claude is beautiful," she muttered,

"isn't he, Hannah? I hope and pray he'll be all right. You pray, too, sweetheart, pray for your little brother."

I watched her drift off right in front of my eyes. Her breathing became soft and regular. For a few moments I sat there, pouting, and then I rose and went back to the nursery to look through the window at my new brother, at the little being who could bring so much joy to my mother and Miguel simply by appearing.

Looking at Claude caused me to wonder about Uncle Linden, born secretly in that beach house, barely knowing his mother before she was sent to my grandfather's clinic. Do babies sense the separation, long for their mothers without even realizing what it is that makes them feel so lost? Was Uncle Linden terrified at night when he cried and was comforted not by his mother, but by his grandmother?

Something made little Claude shudder, and then a moment later he waved his arms and small fists wildly, screaming. No one seemed to notice. I looked about frantically until finally I saw a nurse go to him. She held him for a moment, but that didn't stop his crying. His face looked even redder, and I thought, Do something before he chokes to death on his own tears.

I was about to pound on the glass and shout it, but the nurse smiled as if there was absolutely nothing wrong, then she said something to another nurse and took him out. I worried about where she had taken him until I saw she was bringing him to Mommy's room.

"What's wrong with him?" I asked.

"Nothing. He's just hungry," the nurse replied and went in to wake Mommy so she could breast-feed him. She had decided she would do that.

Nothing brought home little Claude's favored place and status in our family more than watching him suckle at Mommy's breast and seeing the angelic joy in her face. Mommy never told me whether or not she had breast-fed me, and suddenly it became very important to know.

"He's so hungry," Mommy said. "That's good."

"Was I breast-fed, too?" I asked abruptly.

Mommy looked up at me, holding her smile.

"No, actually, you weren't. I was so crazed back then. Your father and I had separated. I was feeling so abused. Despite what everyone was telling me, I couldn't help believing I had permitted him to ruin my life."

"Then you didn't want me to be born?"

"Yes, of course I did. I was just feeling terribly sorry for myself. My mother had died; Linden was not doing very well, as I explained to you, and here I was, pregnant with a husband who considered adultery less important than a parking ticket.

"But the moment you appeared on the scene, it all changed. It was as if the sun had finally come out on a rainy day."

"Then why didn't you breast-feed me, too?"

She hesitated, glanced at Claude, and then looked at me and forced a smile. Mommy's forced smiles always looked like she could go either way: cry or laugh.

"I just told you, Hannah. I was in somewhat of a state of turmoil. I had no one but Miguel really. I needed to get back on my feet as quickly as I could. I tried to stay home with you as long as I could, but eventually, I had to get out in the world and occupy myself. You had a wonderful nanny in Donna Castilla, and Mrs. Davis, bless her soul, watched over you as though you were her very own grandchild. In the beginning I had my hands full arbitrating the arguments between the two of them concerning what was best for you and what was not. Do you remember any of that?"

"A little," I said.

"Yes, well, I'm glad I didn't keep a nanny as long as my stepmother did, even though Amou was more my mother. You, thank goodness, had me and had a stepfather who has always loved you like his own."

"Now he has two children to love," I said.

She gazed down at Claude. I wondered if she could hear my fears in my voice. I really meant he'll love him more. It's only natural, I thought. Claude is his real child and Claude is his son.

"Does that hurt?" I asked.

"Breast-feeding? Just the opposite. However, you won't find many Palm Beach mothers doing it. They're terrified of losing their figures."

"Aren't you?"

"No," she said firmly. "Besides, I want to do what's best for him," she added.

Then why didn't you do what was best for me? I wanted to ask, but I didn't. I watched for a while, and then, after the nurse returned and took Claude back to the nursery, I went to get Mommy some magazines at the hospital gift shop. When I returned to the room, Miguel was there. He was ranting on and on about his faculty meeting, and Mommy was lying back on the pillow, a smile of amusement painted across her face.

"I mean, they will, they won't. Talk, talk, talk, but no action!" he exclaimed.

"They're afraid, Miguel. They have to talk themselves into it first. It takes time."

"Time is not something they have in abundance here, Willow. Oh, what's the use!" he cried and collapsed in the chair, his arms dangling. The he looked up at me and shook his head.

"Don't marry a schoolteacher unless he's independently wealthy," he told me.

"I'm not getting married," I retorted.

"What? Why not?"

"I want to have a career."

"Your mother has a career and she's married," he said, nodding at Mommy.

"She's different," I said. "She can be a psychologist and stay in one place. I will have to travel, do tours, be in shows. I won't have time for a husband and especially not for a child."

"Sure you will," Miguel said.

"No, I won't. I especially won't be able to breast-feed," I practically screamed.

The smile lifted off his face. He looked at Mommy.