Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

Get a behind-the-scenes glimpse of what it takes to be considered one of the worst figures in history, with this brand-new nonfiction series that focuses on the most nefarious historical figures.

On a list of the worst people ever, Adolf Hitler is certainly at or near the top.

Born the son of a low-ranking government official, no one would have predicted that the young Adolf would grow up and become the leader of millions of Germans as well as one of the most despised figures of the twentieth century.

Hitler himself wanted to be an artist, but he couldn’t get into art school. The rejection was just one more thing in a long chain of events that made him angry. Angry at the world. Angry at specific groups of people. As his anger grew, so did his hatred until eventually there was very little else left.

When Hitler entered politics, he found himself surrounded by people who agreed with him. Who would listen to his rants and would happily follow his every decree and cheer his every word.

But why did people let him do that? Why did they follow him? What made his policies so attractive? And what made Adolf Hitler so popular? Find out with this biography that takes a deeper look at Hitler…because history isn’t just about the heroes.

On a list of the worst people ever, Adolf Hitler is certainly at or near the top.

Born the son of a low-ranking government official, no one would have predicted that the young Adolf would grow up and become the leader of millions of Germans as well as one of the most despised figures of the twentieth century.

Hitler himself wanted to be an artist, but he couldn’t get into art school. The rejection was just one more thing in a long chain of events that made him angry. Angry at the world. Angry at specific groups of people. As his anger grew, so did his hatred until eventually there was very little else left.

When Hitler entered politics, he found himself surrounded by people who agreed with him. Who would listen to his rants and would happily follow his every decree and cheer his every word.

But why did people let him do that? Why did they follow him? What made his policies so attractive? And what made Adolf Hitler so popular? Find out with this biography that takes a deeper look at Hitler…because history isn’t just about the heroes.

Excerpt

Adolf Hitler 1 CHILDHOOD

The first thing to know about the man who grew up to transform Germany and who wanted Germans to rule the world is that he wasn’t German.

Hitler’s family was from Austria. In fact, the family name was not even Hitler until 1876. It was originally Schicklgruber. But Hitler’s father, Alois, changed that long name to something a little less clunky. Some sources say “Hitler” was a form of another name from Alois’s family line.

Alois worked for the Austrian government as a customs inspector, examining people and goods coming across the nation’s borders. He had two children—Alois Jr. and Angela—with two different women, and hired his teenage relative Klara to help care for them. Soon Klara was pregnant thanks to Alois. A few years before little Adolf was born, Alois married Klara and they moved into the top floor of an inn in Braunau am Inn, Austria.

The child that caused the marriage, Gustav, was born in 1885 but died shortly after. Another son, Otto, and a daughter, Ida, died very young as well. In the late nineteenth century deadly childhood diseases were not that rare, even in a modern place like Austria.

Alois and Klara kept trying, though, and on April 20, 1889, they welcomed another boy. They named him Adolfus Hitler. And so it started.

WHEN ALOIS GOT a promotion in 1892, the family moved to a new city, Passau. Passau was more than just a new city; it was in a new country. Austria shares a border with Germany, so a few Austrian officials such as Alois lived in that country to help man border stations. Because of this, for the first time in his life, Adolf Hitler was in Germany.

Having lost three other children, Klara was extremely devoted to Adolf. She doted on him constantly, trying to make sure his every need was met, that he was never unhappy. When Adolf was five, his parents added another person to the family, Edmund. Klara still wanted to spoil Adolf, but with a new baby she didn’t have a lot of time to spare. Alois was off at work all day while Klara cared for the kids. Adolf took this opportunity to spend more time outside, on the streets of Passau. He got a taste of real freedom for the first time.

But his period of exploration lasted only a short while. In 1895 Alois moved the family to a farmhouse in the smaller, rural town of Hafeld, back in Austria. It was time for Adolf to start school, and after walking an hour to reach the schoolhouse, he did. Of course he also had to walk an hour home. His older half sister, Angela, recalled that even in those early days Adolf was “a little ringleader.” 1 The unconditional support of his mother gave Adolf a confidence that he used to try to control every situation. He was very sure of himself from an early age, sure that he knew what was going on and that most other people didn’t.

In addition Alois Jr. would say years later that his half brother “was quick to anger from childhood onward and would not listen to anyone. [Klara] always took his side. If he didn’t get his way, he got very angry.” 2

Things changed dramatically in 1895. Alois retired from his government job. It altered the family’s life completely, as Alois turned out to be terrible at retirement. He spent most of his day at home, and when he was not at home, he was hanging with his friends at bars and pubs. His awful temper was made worse by drink, and he took most of it out on Alois Jr., beating him for any slight. Angela and Edmund didn’t fare much better. Adolf was around for these temper tantrums, but most of the anger missed him . . . at first.

The family grew again when a daughter, Paula, was born in 1896. But then the family shrank a year later, when Alois Jr. ran away, unable to put up with his father’s beatings. That left Adolf as the oldest male child to face his father’s anger. They battled constantly, with Klara often comforting her son after one of the father’s rages.

Things improved slightly when Alois moved the family again, this time to Lambach, Austria. Hitler did better in school, with one report card from 1898 showing a stack of ones, the equivalent of As. (In Lambach, as biographer John Toland notes, Hitler went to a nearby church to sing in the choir—apparently the man who would grow to have a powerful speaking voice started out as a lovely young singer—and on his way to the church, he would pass under a stone arch. On it was carved a swastika as part of another design.)

Alois continued to look for a place where he would be comfortable and moved the family again, this time to Leonding, another nearby town but one that was a bit larger and offered him more to do, with concerts, plays, and pubs.

In 1900 the family lost another child when Edmund died of measles. That left Adolf alone with older sister, Angela, and younger sister, Paula. Throughout, Adolf and his father continued to battle. Later his sister Paula would say that Hitler “challenged my father to extreme harshness and . . . got a sound thrashing every day. He was a scrubby little rogue.” 3

At one point when he was eleven, Adolf tried to run away. The windows of their house were barred for security, and he tried to squeeze through. He couldn’t fit. He tried without clothes on and almost made it. Alois discovered him and teased him about having to cover himself with a sheet. If “thrashing” hurt Adolf, this sort of teasing hurt even more.

After every beating and every humiliation, Adolf turned to Klara for comfort. She always supported him, defending him when she could and calming him if possible. Later the family doctor observed that “I have never witnessed closer attachment.” 4 Adolf and Klara were making their once-tight relationship even deeper, though as time went on, he became the dominant figure in it.

Hitler was still doing well at school, even as his home life deteriorated. He found that he was also becoming a good artist. He drew pictures of classmates and of the landscape around their town. He was also reading a lot, especially adventure stories. The American writer James Fenimore Cooper wrote tales of the frontier, starring Native Americans, cowboys, trappers, and explorers. Hitler loved these stories and others of a similar nature written by Karl May, a German writer.

Hitler also read about German history, particularly the war that had not long since been concluded with France—the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. (At that time Prussia was a large independent nation; later it would become part of Germany.) In Mein Kampf (My Struggle), the book Hitler wrote in 1924, he described what he felt after reading about the 1870 war. “From then on I became more enthusiastic about everything that was in any way connected with war or . . . soldiering.” 5

In the fall of 1900, Adolf started at a new school that was three miles away in Linz. The school was the equivalent of junior high, but things did not work out well for him at first. He was the new boy, the country boy, and in the beginning he did not fit in. But showing the skills he had used to dominate at his previous school, Hitler worked to become a leader at the new place. He got the other kids to play cowboys and Indians—apparently he had learned to throw a lasso—and talked with them about wars and soldiers.

At the same time, he started reading Germany mythology and saw his first opera by German composer Richard Wagner. Both of those experiences would become vitally important to him in years to come.

Hitler also continued drawing and painting and was reaching the conclusion that he wanted to be an artist. He did not want to follow in his father’s footsteps and enter government service. Not surprisingly, Alois was not happy about this plan. Hitler’s boyhood friend August Kubizek later wrote that the choice was “the worst possible insult” 6 to Alois. Hitler himself later wrote that Alois screamed, “An artist! Not as long as I live, never!” 7

In 1903, Alois Hitler Sr. died.

The first thing to know about the man who grew up to transform Germany and who wanted Germans to rule the world is that he wasn’t German.

Hitler’s family was from Austria. In fact, the family name was not even Hitler until 1876. It was originally Schicklgruber. But Hitler’s father, Alois, changed that long name to something a little less clunky. Some sources say “Hitler” was a form of another name from Alois’s family line.

Alois worked for the Austrian government as a customs inspector, examining people and goods coming across the nation’s borders. He had two children—Alois Jr. and Angela—with two different women, and hired his teenage relative Klara to help care for them. Soon Klara was pregnant thanks to Alois. A few years before little Adolf was born, Alois married Klara and they moved into the top floor of an inn in Braunau am Inn, Austria.

The child that caused the marriage, Gustav, was born in 1885 but died shortly after. Another son, Otto, and a daughter, Ida, died very young as well. In the late nineteenth century deadly childhood diseases were not that rare, even in a modern place like Austria.

Alois and Klara kept trying, though, and on April 20, 1889, they welcomed another boy. They named him Adolfus Hitler. And so it started.

WHEN ALOIS GOT a promotion in 1892, the family moved to a new city, Passau. Passau was more than just a new city; it was in a new country. Austria shares a border with Germany, so a few Austrian officials such as Alois lived in that country to help man border stations. Because of this, for the first time in his life, Adolf Hitler was in Germany.

Having lost three other children, Klara was extremely devoted to Adolf. She doted on him constantly, trying to make sure his every need was met, that he was never unhappy. When Adolf was five, his parents added another person to the family, Edmund. Klara still wanted to spoil Adolf, but with a new baby she didn’t have a lot of time to spare. Alois was off at work all day while Klara cared for the kids. Adolf took this opportunity to spend more time outside, on the streets of Passau. He got a taste of real freedom for the first time.

But his period of exploration lasted only a short while. In 1895 Alois moved the family to a farmhouse in the smaller, rural town of Hafeld, back in Austria. It was time for Adolf to start school, and after walking an hour to reach the schoolhouse, he did. Of course he also had to walk an hour home. His older half sister, Angela, recalled that even in those early days Adolf was “a little ringleader.” 1 The unconditional support of his mother gave Adolf a confidence that he used to try to control every situation. He was very sure of himself from an early age, sure that he knew what was going on and that most other people didn’t.

In addition Alois Jr. would say years later that his half brother “was quick to anger from childhood onward and would not listen to anyone. [Klara] always took his side. If he didn’t get his way, he got very angry.” 2

Things changed dramatically in 1895. Alois retired from his government job. It altered the family’s life completely, as Alois turned out to be terrible at retirement. He spent most of his day at home, and when he was not at home, he was hanging with his friends at bars and pubs. His awful temper was made worse by drink, and he took most of it out on Alois Jr., beating him for any slight. Angela and Edmund didn’t fare much better. Adolf was around for these temper tantrums, but most of the anger missed him . . . at first.

The family grew again when a daughter, Paula, was born in 1896. But then the family shrank a year later, when Alois Jr. ran away, unable to put up with his father’s beatings. That left Adolf as the oldest male child to face his father’s anger. They battled constantly, with Klara often comforting her son after one of the father’s rages.

Things improved slightly when Alois moved the family again, this time to Lambach, Austria. Hitler did better in school, with one report card from 1898 showing a stack of ones, the equivalent of As. (In Lambach, as biographer John Toland notes, Hitler went to a nearby church to sing in the choir—apparently the man who would grow to have a powerful speaking voice started out as a lovely young singer—and on his way to the church, he would pass under a stone arch. On it was carved a swastika as part of another design.)

Alois continued to look for a place where he would be comfortable and moved the family again, this time to Leonding, another nearby town but one that was a bit larger and offered him more to do, with concerts, plays, and pubs.

In 1900 the family lost another child when Edmund died of measles. That left Adolf alone with older sister, Angela, and younger sister, Paula. Throughout, Adolf and his father continued to battle. Later his sister Paula would say that Hitler “challenged my father to extreme harshness and . . . got a sound thrashing every day. He was a scrubby little rogue.” 3

At one point when he was eleven, Adolf tried to run away. The windows of their house were barred for security, and he tried to squeeze through. He couldn’t fit. He tried without clothes on and almost made it. Alois discovered him and teased him about having to cover himself with a sheet. If “thrashing” hurt Adolf, this sort of teasing hurt even more.

After every beating and every humiliation, Adolf turned to Klara for comfort. She always supported him, defending him when she could and calming him if possible. Later the family doctor observed that “I have never witnessed closer attachment.” 4 Adolf and Klara were making their once-tight relationship even deeper, though as time went on, he became the dominant figure in it.

Hitler was still doing well at school, even as his home life deteriorated. He found that he was also becoming a good artist. He drew pictures of classmates and of the landscape around their town. He was also reading a lot, especially adventure stories. The American writer James Fenimore Cooper wrote tales of the frontier, starring Native Americans, cowboys, trappers, and explorers. Hitler loved these stories and others of a similar nature written by Karl May, a German writer.

Hitler also read about German history, particularly the war that had not long since been concluded with France—the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. (At that time Prussia was a large independent nation; later it would become part of Germany.) In Mein Kampf (My Struggle), the book Hitler wrote in 1924, he described what he felt after reading about the 1870 war. “From then on I became more enthusiastic about everything that was in any way connected with war or . . . soldiering.” 5

In the fall of 1900, Adolf started at a new school that was three miles away in Linz. The school was the equivalent of junior high, but things did not work out well for him at first. He was the new boy, the country boy, and in the beginning he did not fit in. But showing the skills he had used to dominate at his previous school, Hitler worked to become a leader at the new place. He got the other kids to play cowboys and Indians—apparently he had learned to throw a lasso—and talked with them about wars and soldiers.

At the same time, he started reading Germany mythology and saw his first opera by German composer Richard Wagner. Both of those experiences would become vitally important to him in years to come.

Hitler also continued drawing and painting and was reaching the conclusion that he wanted to be an artist. He did not want to follow in his father’s footsteps and enter government service. Not surprisingly, Alois was not happy about this plan. Hitler’s boyhood friend August Kubizek later wrote that the choice was “the worst possible insult” 6 to Alois. Hitler himself later wrote that Alois screamed, “An artist! Not as long as I live, never!” 7

In 1903, Alois Hitler Sr. died.

Product Details

- Publisher: Aladdin (August 15, 2017)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9781481479424

- Ages: 8 - 12

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

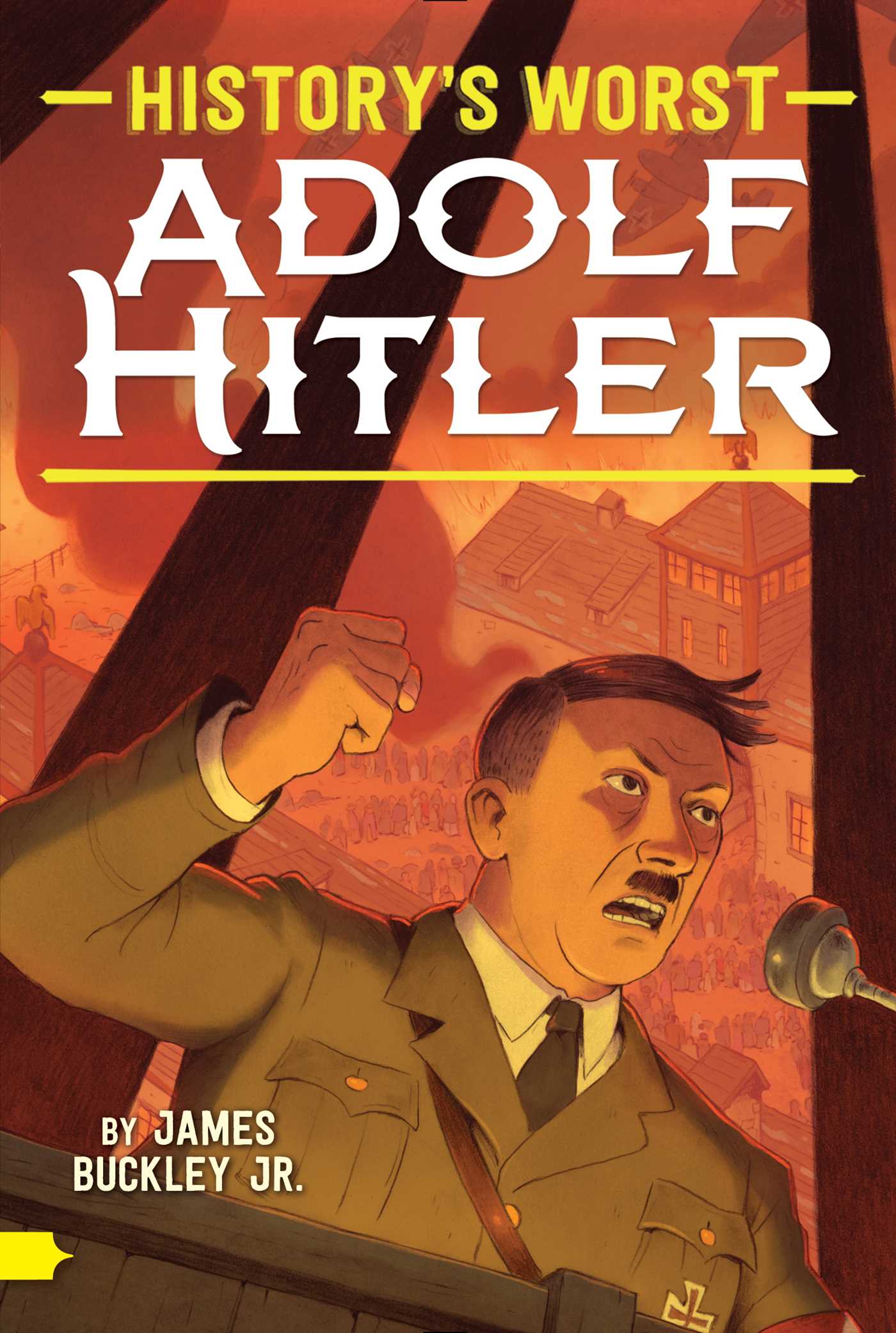

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Adolf Hitler Trade Paperback 9781481479424