Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

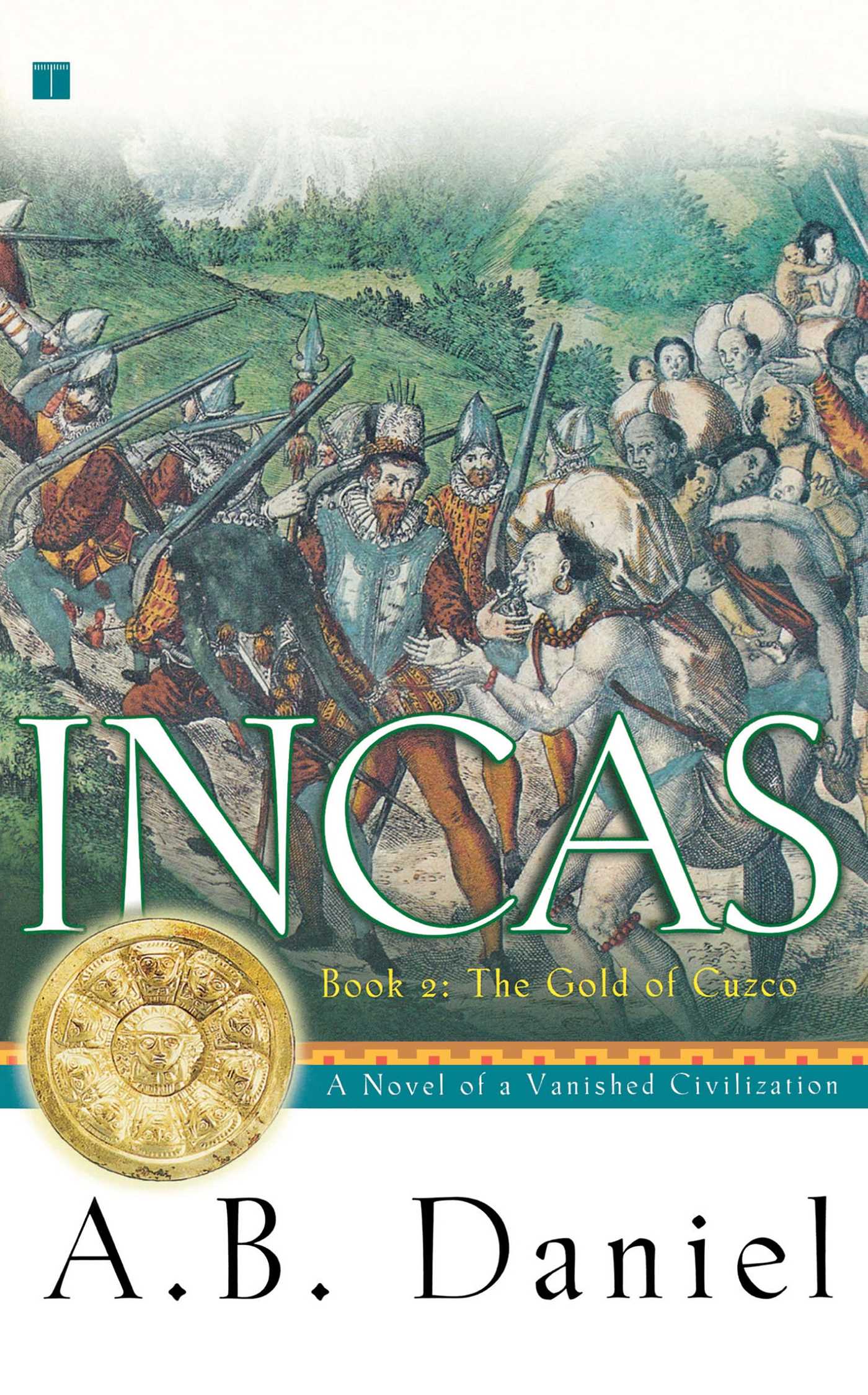

About The Book

In this haunting second book of the internationally bestselling Incas trilogy, the Incan empire is threatened by the Conquistadors, whose insatiable hunger for gold will destroy a glorious, ancient civilization -- unless they can be thwarted by a mystic force greater than any army....

Princess Anamaya's hypnotic blue eyes have seen too much. Having guarded the passage of the dying Emperor, she is now chosen by the gods to stand beside the new Emperor and divine the future of the Incan Empire -- a future shadowed by brutal warriors who worship foreign gods. The Conquistadors and their armies seek to enslave the Incas and loot their sacred temples and royal treasuries, despite Anamaya's attempts to foster peace. When it comes to a prize as valuable as Cuzco, the city of the sacred puma, they refuse to heed her warnings.

The soldier Gabriel has come among Anamaya's people as a conqueror, but the honorable Spaniard is untainted by his companions' lust for wealth and power. His fascination with the splendor of Anamaya's land, and its ancient heritage, is matched only by the passion he and Anamaya come to share. But when his countrymen push forward in their quest to plunder Cuzco, he is forced to join the battle, leaving Anamaya struggling with divided loyalties and their forbidden love in the wake of this first major confrontation between the Spanish and the Incas.

Filled with romance and adventure and colored by the changeless desires that link man and woman throughout the ages, The Gold of Cuzco is a thrilling follow-up to The Puma's Shadow, the first book in the Incas trilogy.

Princess Anamaya's hypnotic blue eyes have seen too much. Having guarded the passage of the dying Emperor, she is now chosen by the gods to stand beside the new Emperor and divine the future of the Incan Empire -- a future shadowed by brutal warriors who worship foreign gods. The Conquistadors and their armies seek to enslave the Incas and loot their sacred temples and royal treasuries, despite Anamaya's attempts to foster peace. When it comes to a prize as valuable as Cuzco, the city of the sacred puma, they refuse to heed her warnings.

The soldier Gabriel has come among Anamaya's people as a conqueror, but the honorable Spaniard is untainted by his companions' lust for wealth and power. His fascination with the splendor of Anamaya's land, and its ancient heritage, is matched only by the passion he and Anamaya come to share. But when his countrymen push forward in their quest to plunder Cuzco, he is forced to join the battle, leaving Anamaya struggling with divided loyalties and their forbidden love in the wake of this first major confrontation between the Spanish and the Incas.

Filled with romance and adventure and colored by the changeless desires that link man and woman throughout the ages, The Gold of Cuzco is a thrilling follow-up to The Puma's Shadow, the first book in the Incas trilogy.

Excerpt

Chapter One

Cajamarca, April 14, 1533, dawn

"I love you," murmured Anamaya in the pale dawn rising over Cajamarca. The darkness of night still lingered, but the smoke rising over the thatched roofs was now slowly turning blue.

Anamaya was alone.

She had stolen away from the palace in which Atahualpa was being kept prisoner. She left it behind her now as she moved like a quick shadow along the narrow streets laid out on the slope overlooking the main square. Soon she was at the river and the access road to the Royal Road.

"I love you," she repeated. "Te quiero!"

The words came to her so easily in the language of the Spaniards that everyone was amazed, whether conquistador or Indian. It had also roused an ancient mistrust among her own people, and once again people were whispering behind her back. But she didn't care.

She ran stealthily alongside the houses, staying close to the shadows of the walls in order to evade the guards watching over Atahualpa's palace and its ransom room piled high with treasure.

The mere sight of this precious haul intoxicated those who had won the Battle of Cajamarca and who had had the audacity to lay their hands on Emperor Atahualpa. It was as though they imagined that gold would yield to them the magical powers that they lacked.

The plunder provoked a deep and silent sadness in Anamaya.

They were insatiable. In search of even more to stuff into the large ransom room, Don Hernando Pizarro had gone to sack the temple at Pachacamac far, far away on the shore of the southern sea. And because his brother was late returning, the Governor, Don Francisco Pizarro, had sent Gabriel and a few reliable men after him.

Gabriel...she allowed his name to settle into her heart, the sound of it so foreign, yet so tender to her....She called to mind his face, his image...the Stranger with sun-colored hair, with pale, pale skin, with the mark of the puma crouching on his shoulder, the mark that was their bond, their secret link, which one day she would reveal to him.

Gabriel had no love of gold. Many times she had watched him stand by indifferent to, even irritated by, his companions' delirious rapture at the mere touch of a few gold leaves.

Gabriel did not accept that an Indian be beaten over a trifle, even less that they be chained or killed.

Gabriel had saved the Emperor from the sword.

Anamaya recalled Atahualpa's words, the words he had spoken when he still had all the power of an emperor. On the eve of the Great Battle, seeing the Strangers for the first time, he had murmured, "I like their horses, but as for them, I don't understand."

Like him, she could have said, "I love one among them, the one who leaped across the ocean for me. But as for the rest of them, I don't understand."

Now she had left behind the high walls surrounding Cajamarca. As she scaled the lower slopes of the Royal Road, she slowed her pace. The adobe-walled houses were fewer now, and set farther apart. Dawn was lighting the mountainsides, breathing life into the corn and quinua fields, rustling in the morning breeze. Occasionally she saw a peasant, already bowed beneath a burden, silhouetted against the growing paleness of day. Anamaya's heart would fill with an uneasy tenderness. She would feel an urge to run to the man and help him carry his burden. She thought about the suffering weighing on her people.

Her people! Because now, she who for so long had been the odd child with blue eyes, the awkward girl who was too tall and too thin, now she knew how much all those who lived in the Inca Empire formed what she called "her people." They didn't all speak the same language or wear the same clothes, and only superficially did they believe in the same gods. Often they had warred among themselves, and the spirit of war was within them still. Yet, in her heart, Anamaya would wish them all blood brothers.

By the time she reached the pass, the day was well established. Light shimmered on the marsh and spread across the immense plain, right up to the mountains concealing the road to Cuzco.

As happened each time she returned here, Anamaya couldn't stop the flood of her memories. She remembered those days in the not-so-distant past when the entire plain had been covered by the white tents of Atahualpa's invincible army. It had been the army of an emperor who had known how to defeat the cruelty of his brother Huascar, the madman of Cuzco.

The steam rose from the baths over on the opposing slope. Atahualpa was resting there, giving thanks to his father Inti by fasting. Her breath short, her heart constricted, Anamaya remembered, as though they were forever tattooed into her skin, those endless days when news of the Strangers' slow approach was brought to them. She remembered those days when everyone scoffed at them, and the fear that she had felt bloom within her. And then she remembered that dawn when all of a sudden he appeared, he, Gabriel. He was so handsome, so attractive that it had been incomprehensible to her.

She didn't want to contemplate what had happened after. The Emperor Atahualpa was but a shadow of his former self, a prisoner in his own palace while his temples were destroyed.

Thus had been accomplished the will of the Sun God.

Thus had been fulfilled the terrible words of the deceased Inca Huayna Capac, who had once come to her in the form of a child and said: "That which is too old comes to an end, that which is too big shatters, that which is too strong loses its force....That is what the great pachacuti means....Some die, and others grow. Have no fear for yourself, Anamaya....You are what you are meant to be. Have no fear, for in the future the puma will go with you!"

Thus, from the other world, the former Inca had simultaneously announced to her Atahualpa's fall and Gabriel's coming!

In truth, ever since her mouth had kissed Gabriel's, ever since she had kissed his strangely marked shoulder, there were many things that Anamaya hadn't been able to understand. There were so many sensations, so many unknown emotions now living within her. And living with so much strength that it seemed as if the claws of a real puma were lacerating her heart.

There were those emotions that urged her to say, "I love you," the words that Gabriel had stubbornly labored to teach her. He had become angry as she had sat there smiling and listening to him, refusing to repeat after him.

And then there was the mystery: How could a Stranger, an enemy, be the puma who would go with her into the future?

Anamaya walked slowly to the end of the plateau that stretched across the peak of the pass. She rolled her cloak about herself and lay down on the still wet grass covering the slope's perpendicular. She gazed at the highest peaks in the east, and contemplated the sun's first rays.

Anamaya closed her eyes. She let the light caress her eyelids and expunge the tears that had formed under them. And as soon as the sun had warmed her face, Gabriel appeared to her against the red underside of her eyelids. Gabriel, the handsome Stranger with eyes like coals, who laughed as innocently as a child, and whose touch was so tender.

Once more her lips formed the words. She whispered them as though they could fly above the earth like hummingbirds: "I love you."

As they approached Cajamarca, Gabriel, unable to check his own momentum, spurred his horse on. He rode to the head of the column at a full trot. His blood boiled. He hadn't slept a wink since his encounter with Hernando three nights earlier. Three nights spent contemplating the stars or sharing the watch at a campsite or a tambo. But today, it was finally over.

He was going to be with her once more.

In a little while he would be gazing into her blue, blue eyes, he would be able to touch her tender mouth, so tender that her kiss melted him, made him oblivious to reality. Only two more leagues and he would be able to see her tall and slender silhouette, unique among Indian women. And the awareness of this alone gnawed at his very core.

He hoped as well that nothing had happened to her during his long absence. There had been talk, as he was leaving Cajamarca, of mariscal Almagro's arrival, Don Francisco's old brother-in-arms, bringing with him yet more troops and more horses.

He was trembling with joy and yet, had he dared, he would have screamed out his lungs in order to banish his fear.

He passed by stretchers borne by Indians on which the heaviest treasures lay: a great gold bowl, a gold statue, a gold chair, and gold mural plaques torn from temple walls. Gold, gold, and yet more gold! It was everywhere -- in wicker baskets, in hide sacks, in woven saddle packs. The porters were bent in half, broken in two under its weight, and the llamas had disappeared beneath their charges. The column had slowed because of it, as though the entire expedition had, since Jauja, become encumbered with all the gold and silver of Peru.

And to think that it was all only a sample: rumor had it that these treasures were nothing in comparison with what would soon arrive from Cuzco. The Governor had sent three men there on a reconnaissance mission, including the execrable Pedro Martín de Moguer.

The Spanish cavalrymen were constantly on the alert. Their nerves frayed, their black gazes mistrustful of everything, they watched for the slightest stir amid the ever docile Indians. Gabriel hadn't many friends within that group. They were all Hernando's men. His personal enmity with the Governor's brother had been well known by all for some time and their duel had frozen them into an icy mutual hatred. The Governor's red-plumed brother went out of his way to avoid Gabriel, more out of caution than astuteness.

As he arrived alongside the palanquins of two high priests from the Pachacamac temple, priests whom Hernando had bound in chains, Gabriel heard a familiar voice hail him:

"Would Your Grace be in a great hurry, at all?"

Gabriel pulled on the reins. With a graceful volte, his horse compliantly came up alongside Sebastian. It had been twenty days now that the big black man, one of Gabriel's few intimate friends, had been on foot. The price of horses had become prohibitive, but more to the point, two days before they had left Pachacamac, Don Hernando had forbidden him from taking the horse from any dying or even dead man.

His insult still pierced shrill in the two friends' ears: "Hola, darkie! Who do you take yourself for? Have you forgotten that horses are reserved for caballeros carrying the sword? It's not because you kicked a few Indian butts that you have the right to take yourself for a man!"

Leaning forward on his horse's neck, Gabriel warmly shook the hand Sebastian was extending to him. The African giant had no horse, but his leather doublet was brand-new and as supple as a second skin. His breeches were tailored with all sorts of fabrics sent from Spain to Cajamarca. They were of the latest fashion out of Castile: large green, red, yellow, and pale blue stripes of felt or satin, and even a little lace on the cords of his boots. The extravagance of his outfit gave Gabriel (who always dressed soberly) the impression of traveling with a retinue of Toledo maidens, their bosoms squeezed into their bodices!

"So where are you trotting off to so quick?" asked Sebastian.

"There's a stench around here," growled Gabriel, looking directly at Hernando's escort. "I need to breathe fresher air."

The black giant gave him a malicious grin.

"Ahh...and there was I thinking that you had an urgency of, how shall I put it, a higher order!"

Gabriel hinted a smile.

"Why, what else could there be other than my haste to present the Governor with my report of my mission?"

"Ho! I see nothing else, indeed."

Sebastian nodded then fell silent, not bantering anymore. Gabriel's gaze fell upon the ridges surrounding Cajamarca. A few months earlier, this alien landscape harbored nothing but menace. Now it had become familiar, almost friendly. And now, of course, it held for him the most beautiful promise.

Gabriel suddenly pulled his right foot out of the stirrup and jumped nimbly to the ground. While he led his horse with one arm, he wrapped the other around Sebastian's shoulders. He leaned in close to his friend.

"You're in the right of it," he said in a low voice, his eyes aglow. "I am in a hurry...and it has nothing to do with that whoreson Hernando."

"Well?"

Gabriel made a vague gesture toward the mountains.

"She says that she can't marry me. She is some sort of priestess in their ancient religion. Marriage is forbidden her, even to an Indian. But still..."

"But still?"

"But still, I love her. Damn and blast it, Sebastian! Just to think of her, my heart explodes like a volley of grapeshot. I love her as though I had never known the meaning of the word before."

Sebastian burst out laughing.

"Do like me, my friend! Love many of them at once! One here, one there, but always one to want you. A tender bed here, a fiery one there...then, you will know what it means to love!"

There was a certain stricture to Gabriel's smile as he returned to his saddle.

"There are times, compañero, when I wish you weren't so witty."

Sebastian hinted at a smile, but his face remained as black as his skin.

"Me too, I wish it. And then again..."

"And then?"

The column had slowed, had grown longer, and now ground to a halt. The Royal Road had grown narrower at the approach to the last peak before Cajamarca.

"And then what?" insisted Gabriel.

Sebastian shook his head. He motioned to Gabriel to gallop up ahead.

"I'll tell you some other time, when you're in less of a hurry."

The hammering that startled Anamaya from her sleep was not that of her heart. It was the stamping of men and horses rising from the earth. She sat up and went and hid in a hedge of acacia and agave close to the Royal Road.

A herd of llamas that had been quietly grazing in a neighboring pasture now shot past and fled, jumping nervously, to the other side of the ridge. The instantly familiar clinking of the Spaniards' iron arms tinkled through the balmy air. It slowly increased in volume along with laughter, bursts of speech, and the click-clacking of hooves on flagstone.

She caught sight of them coming out of a small wood at the foot of the slope. She saw the lances and colorful plumes of the horsemen first, then their somber-bearded faces beneath their morions, before the Indian porters and the Spaniards on foot finally appeared. The entire slow-moving column, led by the Governor's brother, was now visible to her.

Anamaya breathed quick, stuttered gasps of air. She looked for him.

But scrutinize each face, each man's apparel and hat as she might, she couldn't make out Gabriel among the men approaching the ridge. She couldn't make out his black doublet, or his reddish-brown horse with a long white stain on its hindquarters. Nor could she make out the blue scarf he invariably wore around his neck, in order to "carry the color of her eyes with him," as he said, and that normally helped her pick him out from afar.

Anamaya's fingers trembled without her realizing it. Her heart beat strongly, too strongly. She was ashamed of her fear, but she pulled a low branch aside to see more clearly, despite the risk of being seen herself.

At last the blue patch of the scarf fleetingly appeared behind a palanquin. She caught a brief glimpse of the bay. She let out a little spontaneous laugh.

And then she froze.

Her eyes didn't linger on Gabriel. Rather, they remained fixed on the hangings that enclosed the palanquin. She recognized the markings and colors, the slanted lines of blood-red or sky-blue rectangles and triangles.

It was General Chalkuchimac's palanquin. Atahualpa's most powerful warrior.

So the Strangers had convinced him to travel all the way to the Emperor's prison. By what ruse, what treachery had they accomplished this?

Anamaya watched Gabriel pass before the palanquin, as though guarding it. Her heart was no longer beating so fast at the prospect of seeing him. A shadow loomed over her joy.

She understood how things stood. She knew, better than any, what was to become of the Emperor.

A cry caused her to turn around. A small group of riders was coming from the other side of the ridge, negotiating the very steep slope with some difficulty. Leading them was Governor Francisco Pizarro, the first of the Spaniards, dressed all in black, his gray beard standing out against a strange white garment full of holes. A little behind him came Almagro, an undersized man riding a mare far too big for him. He had a frightening face. A green bandana covered one eye. His pockmarked and chapped skin was covered in rusty blotches that the sparse hairs of his beard failed to hide. His too-broad mouth had few teeth. Yet when he spoke his voice was often gentle, almost doleful.

Another cry echoed through the air, followed by others. Laughter resonated; lances and pikes were raised and waved about. When the long column's horsemen were but a stone's throw away from him, Don Francisco jumped agilely from his horse and walked open-armed toward his brother.

Before they had even embraced, Anamaya had already reached the long grass and was running toward the town along the steep shepherds' path.

The ridge's last slope was very steep for the horses. Gabriel cautiously guided his steed, holding the reins chest high. The flagstones were slippery, and the porters faltered. Their talk ended as he approached; it was known among the Indians that he spoke a little of their language.

Calls and cries shot out from the column's head. Gabriel urged on his horse and moved away from the Inca general's palanquin. He saw Hernando Pizarro meet his brother Francisco high up on the flatland at the peak.

Gabriel couldn't help but grin mordaciously. Don Francisco had displayed his loveliest finery in which to welcome his brother. He wore a Cadiz lace ruff around his neck, an article that must have cost him its weight in gold, though it contrasted nicely with his meticulously trimmed beard. But whatever sartorial efforts the Governor made, it was still his brother Hernando, who was bigger and more assured in the strength of his body and the eminence of his origins, who gave the appearance of a genuine prince.

The two brothers embraced effusively before the eyes of the entire company. The Governor's two younger brothers stood a little in the background; the handsome Gonzalo with his dark curls, and the diminutive Juan, with the beauty spot on his neck, watched their embrace with their hats in their hands and grins on their faces.

Gabriel knew what those grins were worth. What really caught his attention was the ill-looking fellow with a scowling face so ugly as to frighten children. Although he had only laid eyes on him a few times, and that was years ago, before they had left for the Peruvian coast, Gabriel instantly recognized him.

So Don Diego de Almagro had indeed come from Panama during his absence! He who, out of his own pocket, had paid for Don Francisco's most ambitious adventure, who had given of himself for it, who had dreamed of becoming an Adelantado alongside his old companion -- now named Governor -- on whom King Charles V had bestowed only the title of lieutenant of Tumbez, with a miserable salary and a hidalgo's title, he had come to claim his due!

The porters resumed their long march. They advanced cautiously down the broad, slippery steps that plunged down to the outskirts of the town. The interpreter Felipillo, his thin lips shut tight, his eyes darting and evasive, stayed close to the richest and most decorated palanquin; he stayed close to Chalkuchimac.

When the palanquin and its retinue reached the square where the Governor, his brothers, and Don Diego de Almagro had already arrived, the palanquin's curtains opened slightly. Gabriel saw a powerful hand appear, large enough to crush a llama's throat.

Felipillo scurried up to the gap, bent double, and murmured a few words that Gabriel couldn't hear.

He stood tall again and barked an order. The porters fell still, their eyes lowered. The hanging enclosing the palanquin slowly rose.

General Chalkuchimac wore a magnificent blue unku made of a blend of cotton and wool. The tunic's weave was strewn with gold sequins. Very fine tocapus outlined a crimson band about his waist. His long, thick hair fell onto his shoulders, partly concealing his gold ear plugs. They seemed smaller than those worn by other nobles that Gabriel had seen. Yet Chalkuchimac's face commanded respect. It was difficult to age him, but he had the power and impassiveness of a statue, as though he had been hewn from a block of sacred rock from the mountains.

He moved forward, and glanced at Gabriel. He growled a few words:

"I must see my master."

Gabriel wasn't sure if he had understood him right. Felipillo was bustling about at the foot of the palanquin. The Inca general raised a hand, pushing him back without even touching him.

Then he approached one of the porters. He took the man's load from him. The porter trembled, his hands empty and his eyes staring doggedly at the ground.

Chalkuchimac placed the enormous basket on his back. Bent double under its weight, he entered the town.

* * *

"Now," affirmed Atahualpa slowly, "they shall free me."

The Emperor was seated on his royal tripod, a cape woven of fine wool hanging over his shoulders. His voice was muted, and hardly broke the silence.

The room was large and always dark. Neither light nor air found their way in, and smoke from the braziers had blackened the stones, the tops of the crimson tapestries, and the building's beams. Many of the niches were empty, or else contained only carved wooden ceremonial vases, albeit magnificent, for sacred beer. The greater part of the gold pots, the silver goblets, and the statues of the gods had all long since been added to the heap in the ransom room.

The Emperor had his servants, wives, and concubines leave the room each time Anamaya visited. It was a moment of intimacy that was all that remained of their lost liberty.

Sunlight only made it as far as the threshold of the opening that gave onto the palace's patio. It threw a pale yellow rectangle on the flagstones.

Atahualpa's silhouette appeared pathetically out of the shadows. Anamaya couldn't help but shiver when she thought that he who had been the Inca, the very brightness of the sun, was slowly slipping toward the Underworld.

The llautu, the royal band, was still on his forehead, and in it the black and white feathers of the curiguingue, the symbol of the Emperor's supreme power. Anamaya noticed that he no longer wore gold plugs in his earlobes. His left lobe, a gaping ring of dead flesh, hung down to his shoulder. His wives had woven him a bandana of the finest alpaca wool to wrap his hair in, and he wore it so that it concealed the torn lobe of his other ear.

Anamaya avoided looking at the pitiful signs of a power in decline. It seemed to her that a little more of Atahualpa's soul left him with each passing day. The virgins still wove his tunics for each new day. He was still served his meals in earthenware that none other used. His retinue, whether they were men or women, and including the few noblemen who were his fellow prisoners in the Cajamarca Palace, still feared his word as they always had. The Strangers bowed before addressing him, and the Spanish Governor accorded him the respect due an emperor. And yet, Anamaya couldn't help but see it all as a masquerade playing itself out. The Emperor had developed a stoop, his face had sallowed, and the red of his eyes had grown bloodier. His mouth was less beautiful, less imperial. His whole body seemed to have shrunken.

The conqueror in him, the son of the great Huayna Capac, had disappeared. Atahualpa was still the Emperor who lived in the Cajamarca Palace, but he was no longer the powerful progeny of the sun who had defeated his brother, the madman of Cuzco. He was but a prisoner without chains who dreamed of his liberation.

Anamaya wanted to tell him what she had seen on the mountain road. She wanted to warn him that Chalkuchimac was there in his palanquin. But she didn't dare, and Atahualpa repeated:

"They have their gold now. They shall let me go."

"I'm not sure," replied Anamaya, looking away.

"What did you say?"

"I'm not sure," she repeated.

Atahualpa gestured irascibly at the ransom room outside.

"I chose the biggest room in my palace, I designated a line on the wall to mark the height of the ransom pile. It has now been reached."

"I remember, my Lord," agreed Anamaya gently. "The Strangers laughed, they thought that you had been seized by madness."

"I told them where to find our gold and silver. I told them that they could take it all, from every house except my father's."

"I know, my Lord."

A sly smile lit Atahualpa's face.

"I realize that I'm talking to the wife of my father's Sacred Double."

Anamaya let a moment pass, and then replied:

"My Lord, those who went to Pachacamac have returned today."

"How do you know this?"

Anamaya made no reply. She didn't want to emphasize the weakness of his position.

Again, the Inca grinned.

"Isn't that what I was telling you? I am going to be freed."

"My Lord," she said in a voice so low that it was barely audible. "The big room is filled with gold, with all our sacred objects, whether they be the most ancient or those that the smiths have only just finished. But the Strangers will not leave your Kingdom. They shall want to go to the Sacred City. They will fill the biggest room, and then they will take the gold of Cuzco. And even if they swore to you by their god and their king not to touch anything belonging to your father, Huayna Capac, the mere sight of the gold will make them forget their promise. You know it, my Lord."

Atahualpa lowered his eyes.

Anamaya didn't want to stop talking now. She continued gently:

"More Strangers will arrive in your kingdom, my Lord. They too will bring weapons and horses, and they too will want gold."

"Yes," murmured Atahualpa. "I don't like that new one, that very ugly one-eyed man."

The words came out of Atahualpa's mouth with difficulty, as though he was a hesitant child once more.

"His name is Almagro."

"I don't like him," repeated the Inca. "His eye lies. He and those who came with him take my women without my permission. They laugh when I forbid it. He says that he is Pizarro's friend, but his eye tells me that it isn't so."

"Why would these men be here, my Lord, if not to take yet more gold?"

"Pizarro's brother will protect me," affirmed Atahualpa. "He is powerful."

"Hernando? Forgive me, my Lord, but don't trust him. His heart is false."

Atahualpa shook his head.

"No! He is powerful, and the others are frightened of him."

"You say that because he has great bearing, because he has a proud eye, and he dresses more carefully than the others, who are slovenly and as dirty as the animals that they have brought with them and that infest our streets. The feather above his helmet may be red, but his soul is black."

A look of shameful hope came over Atahualpa's face.

"He promised that he would help me. If he doesn't..."

His voice lowered a degree. He motioned to Anamaya to approach. A glow of naive excitement had returned to his eyes.

"If he doesn't, the thousands of warriors mobilized by my loyal generals will deliver me. Chalkuchimac is at Jauja, waiting in readiness. He will tell the others..."

Anamaya stifled a cry.

"Oh, my Lord..."

As she hesitated, they heard shouts echoing across the patio. A servant bowed at the threshold of the room. Anamaya knew what he was going to say, and her blood ran cold.

"My Lord...General Chalkuchimac is here. He asks whether you deign to look upon him."

At first, Atahualpa didn't move. Then the full meaning of the words reached him, and the color drained from his face.

"I am a dead man," he whispered.

"May he enter?" asked the servant again, who hadn't heard him.

"I am dead," repeated Atahualpa.

At the palace entrance, Chalkcuchimac hadn't removed the load weighing on his back. Gabriel watched him, broken in two like a supplicant carrying his cross.

Almagro muttered:

"Let us be done with this damned comedy! The only thing this monkey has to do is tell us where he has hidden the rest of the gold."

Don Francisco raised his black-gloved hand.

"Patience, Diego, patience..."

The Inca warriors guarding the entrance to the patio had retreated respectfully before Chalkuchimac. Water spouted from the mouth and the tail of a stone serpent set in a low fountain in the center of the patio. All around bloomed the bright red corollas of the cantuta, the Inca flower. A servant whose only job was to collect its wilted petals stood by them.

Once Chalkuchimac had crawled on his knees into the middle of the courtyard, Atahualpa came out of the room. Gabriel had trouble discerning him. Behind the Inca, in the shadows that half-hid her features, he saw Anamaya.

When at last she lifted her face toward his, he managed to restrain himself from going to her only with the greatest difficulty.

Atahualpa slowly seated himself on a red wood bench, about a palm's height from the ground. It was his usual seat. Some women approached, ready to serve him.

Chalkuchimac at last relieved himself of his charge, unloading it into the hands of a porter who had followed him from the outskirts of town. He removed his sandals and raised his hands toward the cloud-veiled sun, his palms turned skywards.

Tears ran down his rugged face.

Words escaped from his mouth. Gabriel made out a few offerings of gratitude to Inti, and some mumbled words of love for the Inca.

Then Chalkuchimac approached his master. Without stopping crying, he kissed his face, his hands, and his feet.

Atahualpa remained as still as if the general were only a ghost brushing past him. His eyes gazed at an invisible point in the distance. Gabriel had often seen the Inca, but he had never managed to fathom his reactions or his facial expressions.

"You are gladly received, Chalkuchimac," said the Inca eventually. His voice was monotonous and cold.

Chalkuchimac straightened himself up and again raised his palms toward the sky.

"Had I been here," he said in a resonant voice, "none of this would have happened. The Strangers would never have laid a hand on you."

Atahualpa at last turned toward him. Gabriel was trying to catch Anamaya's eye when Don Francisco grabbed his shoulder. Impressed by the events, he said:

"What are they saying?"

"They are greeting one another."

"Strange way to greet," muttered the Governor.

Chalkuchimac stood up. His face had regained its usual impassive and noble composure.

"I waited for your orders, my Lord," he said in a low voice. "Each day, each time that our father the Sun rose into the sky, I felt the urge to come to your rescue. But as you know I could not do so against your wishes. And the chaski bearing your command never came. O my Lord, why did you not order me to annihilate the Strangers?"

Atahualpa made no reply.

The Inca general waited silently for an answer, for some encouraging words. They didn't come. They would never come.

Don Francisco asked again:

"What are they saying now?"

Gabriel felt the infinite and magnificent blue of Anamaya's eyes speak to him, and in that moment he suddenly understood. It was anger that made Atahualpa so still, that had frozen him in that terrible silence.

"The general regrets not having served the Inca better," murmured Gabriel. "He regrets that he has been taken prisoner."

Chalkuchimac took two steps back.

"I waited for your orders, my Lord," he repeated. "We were alone, isolated. Your generals, Quizquiz and Captain Guaypar and the rest, were alone. If you do not order it, they will not come to deliver you."

And with that he turned his back on his master and walked slowly out of the patio, his shoulders sagging as though they bore a heavier load than the one he had entered with.

Gabriel advanced carefully through the dark, feeling his way through the sacks, baskets, and jars.

The secret passage began from the very heart of the palace, from the end of a small room in which the mullus were kept, those pink shells so important during Inca rituals.

Anamaya had revealed it to him shortly after the Great Battle. He had had to promise to keep it secret. He remembered jesting with her, saying, "So, would you mind if I brought the Governor here?"

Back then, the words between them were still uncertain. Deeds had replaced their talk. They could only express and share their love through action. But they hadn't always the opportunity to escape to the cabin by the hot springs, the cabin where they had spent their first night together. So this passage had become their meeting place.

As he crossed the room, Gabriel sank his hand into a large jar of shells. Doing so evoked an oddly agreeable impression of the sea. Those trapezoid niches now so familiar to him surrounded the room. All their gold statues had been removed at the beginning of the Spanish occupation, and they were now covered with cotton hangings. He lifted one, his heart racing.

The tunnel had been dug at a slight rising angle. A thin layer of beaten earth covered the rock. During ancient times, Anamaya had explained to him, the tunnel system had crisscrossed through the entire hill, passing through the acllahuasi and reaching the snail-shaped fortress, the one the conquistadors had demolished upon their arrival.

The passage was remarkably clean and dry, and chests in which reserves of food and clothes had once been stored still sat in recesses at intervals along the way. A rumbling rose up from the belly of the earth: the underground rivers crossing under the mountain.

His eyes had not yet adapted to the darkness, and he uttered a surprised cry when a hand landed on his own, lightly as a butterfly.

"Anamaya!"

Her hand fluttered against his face, landed on his full lips, caressed his cheeks half-hidden under his beard, his eyelids, his forehead. He tried to kiss her, to hold her, but she wrapped him up and dodged him at the same time. They laughed low.

The moment he stopped grasping for her, she stopped evading him. Now he felt her breath close to his own and he made out her proffered face. They both smiled although unable to see one another clearly through the darkness.

"You're here," she whispered.

He sensed in her voice a timidity, or rather a sense of decency, so profound that he was overwhelmed by it. Those simple words had traveled far before reaching her lips.

She was so close that he could smell her scent.

When he drew her close, she surrendered herself modestly to him. Gabriel's arms closed around her, he felt her firm breasts against his chest, her legs against his own. Suddenly they were clutching at one another, their loins inflamed, swamped by the vertigo of desire.

All the energy and frenzy within them, all the accumulated self-constraint of waiting, gushed out in an instant, a sudden, quivering thrill that they appeased with caresses.

Gabriel wanted to be the embodiment of tenderness. His hand disappeared into Anamaya's thick hair. They held one another still for a moment. Their hearts beat so strongly that it felt as though one was beating against the other.

She was the one who placed her lips on his, who touched him, who undressed him, who pushed him back with gentle shoves so that he bent his knees and slowly slid down to the ground.

He felt her mouth traveling over him, running across his face, his neck, his chest, a wave of warmth on his body.

Then he allowed his hands their freedom, and they gripped her smooth, strong thighs, naked under her fine wool tunic. Immobile, they left their mark, and he thought he heard a new murmur, a groan that fused with the rumbling of the rivers.

Anamaya whispered a few lively, happy sounds into his ear, words that he didn't understand.

She is so light, he thought to himself, as their naked bodies burned and melted into each other.

And then, submerged in her caresses, he soared away with her.

Copyright © 2001 by XO Editions. All rights reserved.

Cajamarca, April 14, 1533, dawn

"I love you," murmured Anamaya in the pale dawn rising over Cajamarca. The darkness of night still lingered, but the smoke rising over the thatched roofs was now slowly turning blue.

Anamaya was alone.

She had stolen away from the palace in which Atahualpa was being kept prisoner. She left it behind her now as she moved like a quick shadow along the narrow streets laid out on the slope overlooking the main square. Soon she was at the river and the access road to the Royal Road.

"I love you," she repeated. "Te quiero!"

The words came to her so easily in the language of the Spaniards that everyone was amazed, whether conquistador or Indian. It had also roused an ancient mistrust among her own people, and once again people were whispering behind her back. But she didn't care.

She ran stealthily alongside the houses, staying close to the shadows of the walls in order to evade the guards watching over Atahualpa's palace and its ransom room piled high with treasure.

The mere sight of this precious haul intoxicated those who had won the Battle of Cajamarca and who had had the audacity to lay their hands on Emperor Atahualpa. It was as though they imagined that gold would yield to them the magical powers that they lacked.

The plunder provoked a deep and silent sadness in Anamaya.

They were insatiable. In search of even more to stuff into the large ransom room, Don Hernando Pizarro had gone to sack the temple at Pachacamac far, far away on the shore of the southern sea. And because his brother was late returning, the Governor, Don Francisco Pizarro, had sent Gabriel and a few reliable men after him.

Gabriel...she allowed his name to settle into her heart, the sound of it so foreign, yet so tender to her....She called to mind his face, his image...the Stranger with sun-colored hair, with pale, pale skin, with the mark of the puma crouching on his shoulder, the mark that was their bond, their secret link, which one day she would reveal to him.

Gabriel had no love of gold. Many times she had watched him stand by indifferent to, even irritated by, his companions' delirious rapture at the mere touch of a few gold leaves.

Gabriel did not accept that an Indian be beaten over a trifle, even less that they be chained or killed.

Gabriel had saved the Emperor from the sword.

Anamaya recalled Atahualpa's words, the words he had spoken when he still had all the power of an emperor. On the eve of the Great Battle, seeing the Strangers for the first time, he had murmured, "I like their horses, but as for them, I don't understand."

Like him, she could have said, "I love one among them, the one who leaped across the ocean for me. But as for the rest of them, I don't understand."

Now she had left behind the high walls surrounding Cajamarca. As she scaled the lower slopes of the Royal Road, she slowed her pace. The adobe-walled houses were fewer now, and set farther apart. Dawn was lighting the mountainsides, breathing life into the corn and quinua fields, rustling in the morning breeze. Occasionally she saw a peasant, already bowed beneath a burden, silhouetted against the growing paleness of day. Anamaya's heart would fill with an uneasy tenderness. She would feel an urge to run to the man and help him carry his burden. She thought about the suffering weighing on her people.

Her people! Because now, she who for so long had been the odd child with blue eyes, the awkward girl who was too tall and too thin, now she knew how much all those who lived in the Inca Empire formed what she called "her people." They didn't all speak the same language or wear the same clothes, and only superficially did they believe in the same gods. Often they had warred among themselves, and the spirit of war was within them still. Yet, in her heart, Anamaya would wish them all blood brothers.

By the time she reached the pass, the day was well established. Light shimmered on the marsh and spread across the immense plain, right up to the mountains concealing the road to Cuzco.

As happened each time she returned here, Anamaya couldn't stop the flood of her memories. She remembered those days in the not-so-distant past when the entire plain had been covered by the white tents of Atahualpa's invincible army. It had been the army of an emperor who had known how to defeat the cruelty of his brother Huascar, the madman of Cuzco.

The steam rose from the baths over on the opposing slope. Atahualpa was resting there, giving thanks to his father Inti by fasting. Her breath short, her heart constricted, Anamaya remembered, as though they were forever tattooed into her skin, those endless days when news of the Strangers' slow approach was brought to them. She remembered those days when everyone scoffed at them, and the fear that she had felt bloom within her. And then she remembered that dawn when all of a sudden he appeared, he, Gabriel. He was so handsome, so attractive that it had been incomprehensible to her.

She didn't want to contemplate what had happened after. The Emperor Atahualpa was but a shadow of his former self, a prisoner in his own palace while his temples were destroyed.

Thus had been accomplished the will of the Sun God.

Thus had been fulfilled the terrible words of the deceased Inca Huayna Capac, who had once come to her in the form of a child and said: "That which is too old comes to an end, that which is too big shatters, that which is too strong loses its force....That is what the great pachacuti means....Some die, and others grow. Have no fear for yourself, Anamaya....You are what you are meant to be. Have no fear, for in the future the puma will go with you!"

Thus, from the other world, the former Inca had simultaneously announced to her Atahualpa's fall and Gabriel's coming!

In truth, ever since her mouth had kissed Gabriel's, ever since she had kissed his strangely marked shoulder, there were many things that Anamaya hadn't been able to understand. There were so many sensations, so many unknown emotions now living within her. And living with so much strength that it seemed as if the claws of a real puma were lacerating her heart.

There were those emotions that urged her to say, "I love you," the words that Gabriel had stubbornly labored to teach her. He had become angry as she had sat there smiling and listening to him, refusing to repeat after him.

And then there was the mystery: How could a Stranger, an enemy, be the puma who would go with her into the future?

Anamaya walked slowly to the end of the plateau that stretched across the peak of the pass. She rolled her cloak about herself and lay down on the still wet grass covering the slope's perpendicular. She gazed at the highest peaks in the east, and contemplated the sun's first rays.

Anamaya closed her eyes. She let the light caress her eyelids and expunge the tears that had formed under them. And as soon as the sun had warmed her face, Gabriel appeared to her against the red underside of her eyelids. Gabriel, the handsome Stranger with eyes like coals, who laughed as innocently as a child, and whose touch was so tender.

Once more her lips formed the words. She whispered them as though they could fly above the earth like hummingbirds: "I love you."

As they approached Cajamarca, Gabriel, unable to check his own momentum, spurred his horse on. He rode to the head of the column at a full trot. His blood boiled. He hadn't slept a wink since his encounter with Hernando three nights earlier. Three nights spent contemplating the stars or sharing the watch at a campsite or a tambo. But today, it was finally over.

He was going to be with her once more.

In a little while he would be gazing into her blue, blue eyes, he would be able to touch her tender mouth, so tender that her kiss melted him, made him oblivious to reality. Only two more leagues and he would be able to see her tall and slender silhouette, unique among Indian women. And the awareness of this alone gnawed at his very core.

He hoped as well that nothing had happened to her during his long absence. There had been talk, as he was leaving Cajamarca, of mariscal Almagro's arrival, Don Francisco's old brother-in-arms, bringing with him yet more troops and more horses.

He was trembling with joy and yet, had he dared, he would have screamed out his lungs in order to banish his fear.

He passed by stretchers borne by Indians on which the heaviest treasures lay: a great gold bowl, a gold statue, a gold chair, and gold mural plaques torn from temple walls. Gold, gold, and yet more gold! It was everywhere -- in wicker baskets, in hide sacks, in woven saddle packs. The porters were bent in half, broken in two under its weight, and the llamas had disappeared beneath their charges. The column had slowed because of it, as though the entire expedition had, since Jauja, become encumbered with all the gold and silver of Peru.

And to think that it was all only a sample: rumor had it that these treasures were nothing in comparison with what would soon arrive from Cuzco. The Governor had sent three men there on a reconnaissance mission, including the execrable Pedro Martín de Moguer.

The Spanish cavalrymen were constantly on the alert. Their nerves frayed, their black gazes mistrustful of everything, they watched for the slightest stir amid the ever docile Indians. Gabriel hadn't many friends within that group. They were all Hernando's men. His personal enmity with the Governor's brother had been well known by all for some time and their duel had frozen them into an icy mutual hatred. The Governor's red-plumed brother went out of his way to avoid Gabriel, more out of caution than astuteness.

As he arrived alongside the palanquins of two high priests from the Pachacamac temple, priests whom Hernando had bound in chains, Gabriel heard a familiar voice hail him:

"Would Your Grace be in a great hurry, at all?"

Gabriel pulled on the reins. With a graceful volte, his horse compliantly came up alongside Sebastian. It had been twenty days now that the big black man, one of Gabriel's few intimate friends, had been on foot. The price of horses had become prohibitive, but more to the point, two days before they had left Pachacamac, Don Hernando had forbidden him from taking the horse from any dying or even dead man.

His insult still pierced shrill in the two friends' ears: "Hola, darkie! Who do you take yourself for? Have you forgotten that horses are reserved for caballeros carrying the sword? It's not because you kicked a few Indian butts that you have the right to take yourself for a man!"

Leaning forward on his horse's neck, Gabriel warmly shook the hand Sebastian was extending to him. The African giant had no horse, but his leather doublet was brand-new and as supple as a second skin. His breeches were tailored with all sorts of fabrics sent from Spain to Cajamarca. They were of the latest fashion out of Castile: large green, red, yellow, and pale blue stripes of felt or satin, and even a little lace on the cords of his boots. The extravagance of his outfit gave Gabriel (who always dressed soberly) the impression of traveling with a retinue of Toledo maidens, their bosoms squeezed into their bodices!

"So where are you trotting off to so quick?" asked Sebastian.

"There's a stench around here," growled Gabriel, looking directly at Hernando's escort. "I need to breathe fresher air."

The black giant gave him a malicious grin.

"Ahh...and there was I thinking that you had an urgency of, how shall I put it, a higher order!"

Gabriel hinted a smile.

"Why, what else could there be other than my haste to present the Governor with my report of my mission?"

"Ho! I see nothing else, indeed."

Sebastian nodded then fell silent, not bantering anymore. Gabriel's gaze fell upon the ridges surrounding Cajamarca. A few months earlier, this alien landscape harbored nothing but menace. Now it had become familiar, almost friendly. And now, of course, it held for him the most beautiful promise.

Gabriel suddenly pulled his right foot out of the stirrup and jumped nimbly to the ground. While he led his horse with one arm, he wrapped the other around Sebastian's shoulders. He leaned in close to his friend.

"You're in the right of it," he said in a low voice, his eyes aglow. "I am in a hurry...and it has nothing to do with that whoreson Hernando."

"Well?"

Gabriel made a vague gesture toward the mountains.

"She says that she can't marry me. She is some sort of priestess in their ancient religion. Marriage is forbidden her, even to an Indian. But still..."

"But still?"

"But still, I love her. Damn and blast it, Sebastian! Just to think of her, my heart explodes like a volley of grapeshot. I love her as though I had never known the meaning of the word before."

Sebastian burst out laughing.

"Do like me, my friend! Love many of them at once! One here, one there, but always one to want you. A tender bed here, a fiery one there...then, you will know what it means to love!"

There was a certain stricture to Gabriel's smile as he returned to his saddle.

"There are times, compañero, when I wish you weren't so witty."

Sebastian hinted at a smile, but his face remained as black as his skin.

"Me too, I wish it. And then again..."

"And then?"

The column had slowed, had grown longer, and now ground to a halt. The Royal Road had grown narrower at the approach to the last peak before Cajamarca.

"And then what?" insisted Gabriel.

Sebastian shook his head. He motioned to Gabriel to gallop up ahead.

"I'll tell you some other time, when you're in less of a hurry."

The hammering that startled Anamaya from her sleep was not that of her heart. It was the stamping of men and horses rising from the earth. She sat up and went and hid in a hedge of acacia and agave close to the Royal Road.

A herd of llamas that had been quietly grazing in a neighboring pasture now shot past and fled, jumping nervously, to the other side of the ridge. The instantly familiar clinking of the Spaniards' iron arms tinkled through the balmy air. It slowly increased in volume along with laughter, bursts of speech, and the click-clacking of hooves on flagstone.

She caught sight of them coming out of a small wood at the foot of the slope. She saw the lances and colorful plumes of the horsemen first, then their somber-bearded faces beneath their morions, before the Indian porters and the Spaniards on foot finally appeared. The entire slow-moving column, led by the Governor's brother, was now visible to her.

Anamaya breathed quick, stuttered gasps of air. She looked for him.

But scrutinize each face, each man's apparel and hat as she might, she couldn't make out Gabriel among the men approaching the ridge. She couldn't make out his black doublet, or his reddish-brown horse with a long white stain on its hindquarters. Nor could she make out the blue scarf he invariably wore around his neck, in order to "carry the color of her eyes with him," as he said, and that normally helped her pick him out from afar.

Anamaya's fingers trembled without her realizing it. Her heart beat strongly, too strongly. She was ashamed of her fear, but she pulled a low branch aside to see more clearly, despite the risk of being seen herself.

At last the blue patch of the scarf fleetingly appeared behind a palanquin. She caught a brief glimpse of the bay. She let out a little spontaneous laugh.

And then she froze.

Her eyes didn't linger on Gabriel. Rather, they remained fixed on the hangings that enclosed the palanquin. She recognized the markings and colors, the slanted lines of blood-red or sky-blue rectangles and triangles.

It was General Chalkuchimac's palanquin. Atahualpa's most powerful warrior.

So the Strangers had convinced him to travel all the way to the Emperor's prison. By what ruse, what treachery had they accomplished this?

Anamaya watched Gabriel pass before the palanquin, as though guarding it. Her heart was no longer beating so fast at the prospect of seeing him. A shadow loomed over her joy.

She understood how things stood. She knew, better than any, what was to become of the Emperor.

A cry caused her to turn around. A small group of riders was coming from the other side of the ridge, negotiating the very steep slope with some difficulty. Leading them was Governor Francisco Pizarro, the first of the Spaniards, dressed all in black, his gray beard standing out against a strange white garment full of holes. A little behind him came Almagro, an undersized man riding a mare far too big for him. He had a frightening face. A green bandana covered one eye. His pockmarked and chapped skin was covered in rusty blotches that the sparse hairs of his beard failed to hide. His too-broad mouth had few teeth. Yet when he spoke his voice was often gentle, almost doleful.

Another cry echoed through the air, followed by others. Laughter resonated; lances and pikes were raised and waved about. When the long column's horsemen were but a stone's throw away from him, Don Francisco jumped agilely from his horse and walked open-armed toward his brother.

Before they had even embraced, Anamaya had already reached the long grass and was running toward the town along the steep shepherds' path.

The ridge's last slope was very steep for the horses. Gabriel cautiously guided his steed, holding the reins chest high. The flagstones were slippery, and the porters faltered. Their talk ended as he approached; it was known among the Indians that he spoke a little of their language.

Calls and cries shot out from the column's head. Gabriel urged on his horse and moved away from the Inca general's palanquin. He saw Hernando Pizarro meet his brother Francisco high up on the flatland at the peak.

Gabriel couldn't help but grin mordaciously. Don Francisco had displayed his loveliest finery in which to welcome his brother. He wore a Cadiz lace ruff around his neck, an article that must have cost him its weight in gold, though it contrasted nicely with his meticulously trimmed beard. But whatever sartorial efforts the Governor made, it was still his brother Hernando, who was bigger and more assured in the strength of his body and the eminence of his origins, who gave the appearance of a genuine prince.

The two brothers embraced effusively before the eyes of the entire company. The Governor's two younger brothers stood a little in the background; the handsome Gonzalo with his dark curls, and the diminutive Juan, with the beauty spot on his neck, watched their embrace with their hats in their hands and grins on their faces.

Gabriel knew what those grins were worth. What really caught his attention was the ill-looking fellow with a scowling face so ugly as to frighten children. Although he had only laid eyes on him a few times, and that was years ago, before they had left for the Peruvian coast, Gabriel instantly recognized him.

So Don Diego de Almagro had indeed come from Panama during his absence! He who, out of his own pocket, had paid for Don Francisco's most ambitious adventure, who had given of himself for it, who had dreamed of becoming an Adelantado alongside his old companion -- now named Governor -- on whom King Charles V had bestowed only the title of lieutenant of Tumbez, with a miserable salary and a hidalgo's title, he had come to claim his due!

The porters resumed their long march. They advanced cautiously down the broad, slippery steps that plunged down to the outskirts of the town. The interpreter Felipillo, his thin lips shut tight, his eyes darting and evasive, stayed close to the richest and most decorated palanquin; he stayed close to Chalkuchimac.

When the palanquin and its retinue reached the square where the Governor, his brothers, and Don Diego de Almagro had already arrived, the palanquin's curtains opened slightly. Gabriel saw a powerful hand appear, large enough to crush a llama's throat.

Felipillo scurried up to the gap, bent double, and murmured a few words that Gabriel couldn't hear.

He stood tall again and barked an order. The porters fell still, their eyes lowered. The hanging enclosing the palanquin slowly rose.

General Chalkuchimac wore a magnificent blue unku made of a blend of cotton and wool. The tunic's weave was strewn with gold sequins. Very fine tocapus outlined a crimson band about his waist. His long, thick hair fell onto his shoulders, partly concealing his gold ear plugs. They seemed smaller than those worn by other nobles that Gabriel had seen. Yet Chalkuchimac's face commanded respect. It was difficult to age him, but he had the power and impassiveness of a statue, as though he had been hewn from a block of sacred rock from the mountains.

He moved forward, and glanced at Gabriel. He growled a few words:

"I must see my master."

Gabriel wasn't sure if he had understood him right. Felipillo was bustling about at the foot of the palanquin. The Inca general raised a hand, pushing him back without even touching him.

Then he approached one of the porters. He took the man's load from him. The porter trembled, his hands empty and his eyes staring doggedly at the ground.

Chalkuchimac placed the enormous basket on his back. Bent double under its weight, he entered the town.

* * *

"Now," affirmed Atahualpa slowly, "they shall free me."

The Emperor was seated on his royal tripod, a cape woven of fine wool hanging over his shoulders. His voice was muted, and hardly broke the silence.

The room was large and always dark. Neither light nor air found their way in, and smoke from the braziers had blackened the stones, the tops of the crimson tapestries, and the building's beams. Many of the niches were empty, or else contained only carved wooden ceremonial vases, albeit magnificent, for sacred beer. The greater part of the gold pots, the silver goblets, and the statues of the gods had all long since been added to the heap in the ransom room.

The Emperor had his servants, wives, and concubines leave the room each time Anamaya visited. It was a moment of intimacy that was all that remained of their lost liberty.

Sunlight only made it as far as the threshold of the opening that gave onto the palace's patio. It threw a pale yellow rectangle on the flagstones.

Atahualpa's silhouette appeared pathetically out of the shadows. Anamaya couldn't help but shiver when she thought that he who had been the Inca, the very brightness of the sun, was slowly slipping toward the Underworld.

The llautu, the royal band, was still on his forehead, and in it the black and white feathers of the curiguingue, the symbol of the Emperor's supreme power. Anamaya noticed that he no longer wore gold plugs in his earlobes. His left lobe, a gaping ring of dead flesh, hung down to his shoulder. His wives had woven him a bandana of the finest alpaca wool to wrap his hair in, and he wore it so that it concealed the torn lobe of his other ear.

Anamaya avoided looking at the pitiful signs of a power in decline. It seemed to her that a little more of Atahualpa's soul left him with each passing day. The virgins still wove his tunics for each new day. He was still served his meals in earthenware that none other used. His retinue, whether they were men or women, and including the few noblemen who were his fellow prisoners in the Cajamarca Palace, still feared his word as they always had. The Strangers bowed before addressing him, and the Spanish Governor accorded him the respect due an emperor. And yet, Anamaya couldn't help but see it all as a masquerade playing itself out. The Emperor had developed a stoop, his face had sallowed, and the red of his eyes had grown bloodier. His mouth was less beautiful, less imperial. His whole body seemed to have shrunken.

The conqueror in him, the son of the great Huayna Capac, had disappeared. Atahualpa was still the Emperor who lived in the Cajamarca Palace, but he was no longer the powerful progeny of the sun who had defeated his brother, the madman of Cuzco. He was but a prisoner without chains who dreamed of his liberation.

Anamaya wanted to tell him what she had seen on the mountain road. She wanted to warn him that Chalkuchimac was there in his palanquin. But she didn't dare, and Atahualpa repeated:

"They have their gold now. They shall let me go."

"I'm not sure," replied Anamaya, looking away.

"What did you say?"

"I'm not sure," she repeated.

Atahualpa gestured irascibly at the ransom room outside.

"I chose the biggest room in my palace, I designated a line on the wall to mark the height of the ransom pile. It has now been reached."

"I remember, my Lord," agreed Anamaya gently. "The Strangers laughed, they thought that you had been seized by madness."

"I told them where to find our gold and silver. I told them that they could take it all, from every house except my father's."

"I know, my Lord."

A sly smile lit Atahualpa's face.

"I realize that I'm talking to the wife of my father's Sacred Double."

Anamaya let a moment pass, and then replied:

"My Lord, those who went to Pachacamac have returned today."

"How do you know this?"

Anamaya made no reply. She didn't want to emphasize the weakness of his position.

Again, the Inca grinned.

"Isn't that what I was telling you? I am going to be freed."

"My Lord," she said in a voice so low that it was barely audible. "The big room is filled with gold, with all our sacred objects, whether they be the most ancient or those that the smiths have only just finished. But the Strangers will not leave your Kingdom. They shall want to go to the Sacred City. They will fill the biggest room, and then they will take the gold of Cuzco. And even if they swore to you by their god and their king not to touch anything belonging to your father, Huayna Capac, the mere sight of the gold will make them forget their promise. You know it, my Lord."

Atahualpa lowered his eyes.

Anamaya didn't want to stop talking now. She continued gently:

"More Strangers will arrive in your kingdom, my Lord. They too will bring weapons and horses, and they too will want gold."

"Yes," murmured Atahualpa. "I don't like that new one, that very ugly one-eyed man."

The words came out of Atahualpa's mouth with difficulty, as though he was a hesitant child once more.

"His name is Almagro."

"I don't like him," repeated the Inca. "His eye lies. He and those who came with him take my women without my permission. They laugh when I forbid it. He says that he is Pizarro's friend, but his eye tells me that it isn't so."

"Why would these men be here, my Lord, if not to take yet more gold?"

"Pizarro's brother will protect me," affirmed Atahualpa. "He is powerful."

"Hernando? Forgive me, my Lord, but don't trust him. His heart is false."

Atahualpa shook his head.

"No! He is powerful, and the others are frightened of him."

"You say that because he has great bearing, because he has a proud eye, and he dresses more carefully than the others, who are slovenly and as dirty as the animals that they have brought with them and that infest our streets. The feather above his helmet may be red, but his soul is black."

A look of shameful hope came over Atahualpa's face.

"He promised that he would help me. If he doesn't..."

His voice lowered a degree. He motioned to Anamaya to approach. A glow of naive excitement had returned to his eyes.

"If he doesn't, the thousands of warriors mobilized by my loyal generals will deliver me. Chalkuchimac is at Jauja, waiting in readiness. He will tell the others..."

Anamaya stifled a cry.

"Oh, my Lord..."

As she hesitated, they heard shouts echoing across the patio. A servant bowed at the threshold of the room. Anamaya knew what he was going to say, and her blood ran cold.

"My Lord...General Chalkuchimac is here. He asks whether you deign to look upon him."

At first, Atahualpa didn't move. Then the full meaning of the words reached him, and the color drained from his face.

"I am a dead man," he whispered.

"May he enter?" asked the servant again, who hadn't heard him.

"I am dead," repeated Atahualpa.

At the palace entrance, Chalkcuchimac hadn't removed the load weighing on his back. Gabriel watched him, broken in two like a supplicant carrying his cross.

Almagro muttered:

"Let us be done with this damned comedy! The only thing this monkey has to do is tell us where he has hidden the rest of the gold."

Don Francisco raised his black-gloved hand.

"Patience, Diego, patience..."

The Inca warriors guarding the entrance to the patio had retreated respectfully before Chalkuchimac. Water spouted from the mouth and the tail of a stone serpent set in a low fountain in the center of the patio. All around bloomed the bright red corollas of the cantuta, the Inca flower. A servant whose only job was to collect its wilted petals stood by them.

Once Chalkuchimac had crawled on his knees into the middle of the courtyard, Atahualpa came out of the room. Gabriel had trouble discerning him. Behind the Inca, in the shadows that half-hid her features, he saw Anamaya.

When at last she lifted her face toward his, he managed to restrain himself from going to her only with the greatest difficulty.

Atahualpa slowly seated himself on a red wood bench, about a palm's height from the ground. It was his usual seat. Some women approached, ready to serve him.

Chalkuchimac at last relieved himself of his charge, unloading it into the hands of a porter who had followed him from the outskirts of town. He removed his sandals and raised his hands toward the cloud-veiled sun, his palms turned skywards.

Tears ran down his rugged face.

Words escaped from his mouth. Gabriel made out a few offerings of gratitude to Inti, and some mumbled words of love for the Inca.

Then Chalkuchimac approached his master. Without stopping crying, he kissed his face, his hands, and his feet.

Atahualpa remained as still as if the general were only a ghost brushing past him. His eyes gazed at an invisible point in the distance. Gabriel had often seen the Inca, but he had never managed to fathom his reactions or his facial expressions.

"You are gladly received, Chalkuchimac," said the Inca eventually. His voice was monotonous and cold.

Chalkuchimac straightened himself up and again raised his palms toward the sky.

"Had I been here," he said in a resonant voice, "none of this would have happened. The Strangers would never have laid a hand on you."

Atahualpa at last turned toward him. Gabriel was trying to catch Anamaya's eye when Don Francisco grabbed his shoulder. Impressed by the events, he said:

"What are they saying?"

"They are greeting one another."

"Strange way to greet," muttered the Governor.

Chalkuchimac stood up. His face had regained its usual impassive and noble composure.

"I waited for your orders, my Lord," he said in a low voice. "Each day, each time that our father the Sun rose into the sky, I felt the urge to come to your rescue. But as you know I could not do so against your wishes. And the chaski bearing your command never came. O my Lord, why did you not order me to annihilate the Strangers?"

Atahualpa made no reply.

The Inca general waited silently for an answer, for some encouraging words. They didn't come. They would never come.

Don Francisco asked again:

"What are they saying now?"

Gabriel felt the infinite and magnificent blue of Anamaya's eyes speak to him, and in that moment he suddenly understood. It was anger that made Atahualpa so still, that had frozen him in that terrible silence.

"The general regrets not having served the Inca better," murmured Gabriel. "He regrets that he has been taken prisoner."

Chalkuchimac took two steps back.

"I waited for your orders, my Lord," he repeated. "We were alone, isolated. Your generals, Quizquiz and Captain Guaypar and the rest, were alone. If you do not order it, they will not come to deliver you."

And with that he turned his back on his master and walked slowly out of the patio, his shoulders sagging as though they bore a heavier load than the one he had entered with.

Gabriel advanced carefully through the dark, feeling his way through the sacks, baskets, and jars.

The secret passage began from the very heart of the palace, from the end of a small room in which the mullus were kept, those pink shells so important during Inca rituals.

Anamaya had revealed it to him shortly after the Great Battle. He had had to promise to keep it secret. He remembered jesting with her, saying, "So, would you mind if I brought the Governor here?"

Back then, the words between them were still uncertain. Deeds had replaced their talk. They could only express and share their love through action. But they hadn't always the opportunity to escape to the cabin by the hot springs, the cabin where they had spent their first night together. So this passage had become their meeting place.

As he crossed the room, Gabriel sank his hand into a large jar of shells. Doing so evoked an oddly agreeable impression of the sea. Those trapezoid niches now so familiar to him surrounded the room. All their gold statues had been removed at the beginning of the Spanish occupation, and they were now covered with cotton hangings. He lifted one, his heart racing.

The tunnel had been dug at a slight rising angle. A thin layer of beaten earth covered the rock. During ancient times, Anamaya had explained to him, the tunnel system had crisscrossed through the entire hill, passing through the acllahuasi and reaching the snail-shaped fortress, the one the conquistadors had demolished upon their arrival.

The passage was remarkably clean and dry, and chests in which reserves of food and clothes had once been stored still sat in recesses at intervals along the way. A rumbling rose up from the belly of the earth: the underground rivers crossing under the mountain.

His eyes had not yet adapted to the darkness, and he uttered a surprised cry when a hand landed on his own, lightly as a butterfly.

"Anamaya!"

Her hand fluttered against his face, landed on his full lips, caressed his cheeks half-hidden under his beard, his eyelids, his forehead. He tried to kiss her, to hold her, but she wrapped him up and dodged him at the same time. They laughed low.

The moment he stopped grasping for her, she stopped evading him. Now he felt her breath close to his own and he made out her proffered face. They both smiled although unable to see one another clearly through the darkness.

"You're here," she whispered.

He sensed in her voice a timidity, or rather a sense of decency, so profound that he was overwhelmed by it. Those simple words had traveled far before reaching her lips.

She was so close that he could smell her scent.

When he drew her close, she surrendered herself modestly to him. Gabriel's arms closed around her, he felt her firm breasts against his chest, her legs against his own. Suddenly they were clutching at one another, their loins inflamed, swamped by the vertigo of desire.

All the energy and frenzy within them, all the accumulated self-constraint of waiting, gushed out in an instant, a sudden, quivering thrill that they appeased with caresses.

Gabriel wanted to be the embodiment of tenderness. His hand disappeared into Anamaya's thick hair. They held one another still for a moment. Their hearts beat so strongly that it felt as though one was beating against the other.

She was the one who placed her lips on his, who touched him, who undressed him, who pushed him back with gentle shoves so that he bent his knees and slowly slid down to the ground.

He felt her mouth traveling over him, running across his face, his neck, his chest, a wave of warmth on his body.

Then he allowed his hands their freedom, and they gripped her smooth, strong thighs, naked under her fine wool tunic. Immobile, they left their mark, and he thought he heard a new murmur, a groan that fused with the rumbling of the rivers.

Anamaya whispered a few lively, happy sounds into his ear, words that he didn't understand.

She is so light, he thought to himself, as their naked bodies burned and melted into each other.

And then, submerged in her caresses, he soared away with her.

Copyright © 2001 by XO Editions. All rights reserved.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (December 3, 2002)

- Length: 384 pages

- ISBN13: 9780743432757

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Incas Trade Paperback 9780743432757