Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

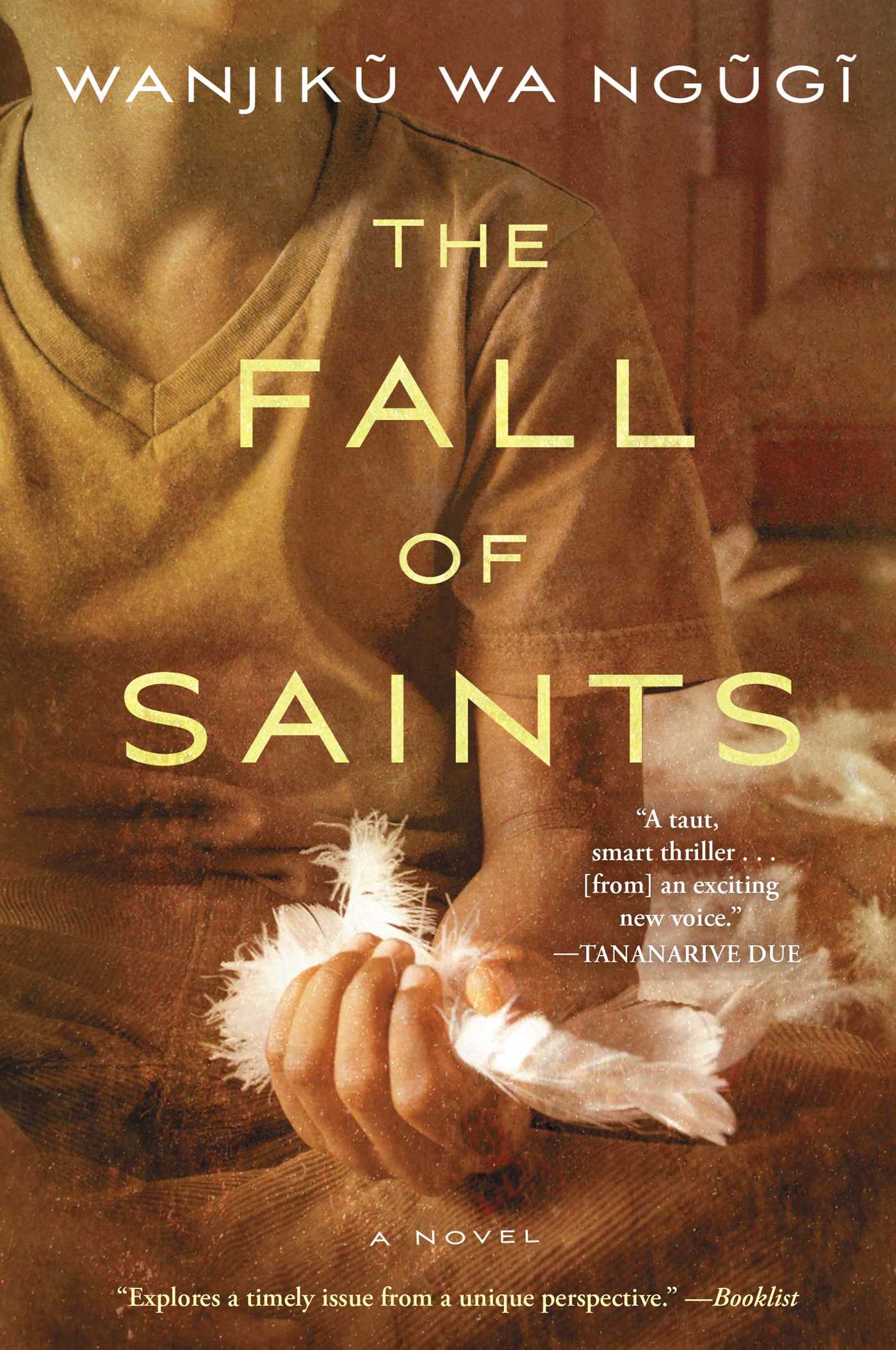

In this “taut, smart international thriller” (Tananarive Due, American Book Award winner), a Kenyan expat finds her American dream marred by child trafficking, scandal, and a problematic past that will force an end to her life of privilege.

Mugure and Zack seem to have the picture-perfect family: a young, healthy son, a beautiful home in Riverdale, New York, and a bright future. But one night, as Mugure is rummaging through an old drawer, she comes across a piece of paper with a note scrawled on it—a note that calls into question everything she’s ever believed about her husband…

A wandering curiosity may have gotten the best of Mugure this time as she heads down a dangerous road that takes her back to Kenya, where new discoveries threaten to undo her idyllic life. She wonders if she ever really knew the man she married and begins to piece together the signs that were there since the beginning. Who was that suspicious man who trailed Zack and Mugure on their first date at a New York nightclub? What about the closing of the agency that facilitated the adoption of their son?

Through a striking, beautifully rendered story, The Fall of Saints tackles realistic political and ethical issues head-on. This “fast-paced and urgent read that forces us to consider one of the worst human rights violations of our time” (asha bandele, author of The Prisoner’s Wife) will tug at your heart and keep it racing until the end.

Mugure and Zack seem to have the picture-perfect family: a young, healthy son, a beautiful home in Riverdale, New York, and a bright future. But one night, as Mugure is rummaging through an old drawer, she comes across a piece of paper with a note scrawled on it—a note that calls into question everything she’s ever believed about her husband…

A wandering curiosity may have gotten the best of Mugure this time as she heads down a dangerous road that takes her back to Kenya, where new discoveries threaten to undo her idyllic life. She wonders if she ever really knew the man she married and begins to piece together the signs that were there since the beginning. Who was that suspicious man who trailed Zack and Mugure on their first date at a New York nightclub? What about the closing of the agency that facilitated the adoption of their son?

Through a striking, beautifully rendered story, The Fall of Saints tackles realistic political and ethical issues head-on. This “fast-paced and urgent read that forces us to consider one of the worst human rights violations of our time” (asha bandele, author of The Prisoner’s Wife) will tug at your heart and keep it racing until the end.

Excerpt

The Fall of Saints

1

My cell phone rang. I assumed it was from Detective Ben Underwood again. I looked at the backseat, where my son, Kobi, excitedly cradled his soccer ball; he had scored the winning goal for his side. I answered the phone and asked, “Hey, got more details?”

I heard muffled noise followed by shallow breathing. I took the phone from my ear and checked the caller ID. PRIVATE, it read. It was not Ben.

“Hello . . . Hello?”

No answer. I hung up. It rang again. The same muffled noise.

“What do you want?” I asked, irritated, thinking it was a telemarketer.

“Take this from a friend,” said a deep voice in a put-on Jamaican accent. “You ask too many questions.”

“Who are you?”

“Just stop it.” And the line went dead.

I looked around the car in panic. I instinctively reached out to Kobi, to reassure him, but more myself. He had been through enough in his journey into our lives. But of course only I heard the threat. My hands were shaking. Compose yourself, Mugure. There is nothing to this. A crank call.

I dialed Ben and went over every detail of what had just taken place.

“Are you sure?” he asked.

I felt irritated by his question. “Think I’m making it up?”

“No, no,” Ben protested, and told me to let him know if the person called again. “But, Mugure, be careful,” he said before he hung up.

I was relieved when Kobi and I found Zack at home. Everything appeared normal again. But I sensed something had come undone.

• • •

I first met my husband, Zack, at the office of Okigbo & Okigbo, a law firm in Manhattan, on Canal Street, not far from south Broadway. Actually, the firm was not a partnership, but the double-barreled title made the sole proprietorship appear bigger and more powerful. I was coming from the bathroom back to the reception desk when I literally walked into Zack. His papers went flying all over the corridor.

“Body screening?” he said as I quickly ran about, collecting the papers.

I brought them back, trying to align them, and came face-to-face with a tall, preppy, but strikingly good-looking blond man. He almost let the papers fall again as he frowned and gave me a long hard look. Disapproval, I thought.

“I am really sorry, sir,” I managed with a sheepish smile.

“I should sue you for invading my privacy,” he said. In what seemed a quick afterthought, he added, “But a cup of coffee would make me forget this ever happened.”

“Sounds like a plan,” I said without thinking, but then I would have said anything to end the embarrassment.

He had come to meet with my boss for a deposition in a case of medical malpractice. I pointed in the direction of Mr. Okigbo’s office. He didn’t budge. He continued standing there, as if studying me.

“Umm . . . your number,” he said at last.

“Oh, yes, of course, one second, sir. If you can come this way, please,” I said, leading him toward Okigbo’s office, fumbling in my bag for a card, anything to get him away.

“Mugure. Office manager,” he said, glancing at the card.

I hoped he was not being sarcastic about the pretentious title. I was a part-time receptionist and a glorified all-purpose messenger. To complete “all-purpose” for the same wages, Okigbo wanted to have me trained as an armed security guard and even had me go to a shooting range. When my eyes closed and my hands trembled involuntarily at the sight of a gun, my would-be trainer returned a verdict of hopeless that ended whatever security ambitions Okigbo had in store for me.

“Zack Sivonen,” he said, “Edward and Palmer Advocates,” which was unnecessary because the name and its location, in lower Manhattan, were on the card he gave me. He entered Mr. Okigbo’s office. I noticed that he walked with a slight limp, but it suited him, as if it were a style he had cultivated.

On our first date, Zack took me to Shamrock, a club in the basement of a sex shop on Forty-Second Street between Sixth and Eighth Avenues, the red-light district of New York City. Blue fluorescent bulbs lit our descent into a dungeon. Even when the lighting changed into a clearer soft yellow, the atmosphere remained eerie, as in a horror film. The ambient smoke made me cough.

“It gets better, I promise,” Zack said, noting my discomfort.

“I sure hope so,” I said.

I began to make out the outlines of things. One section of the wall was decorated with colorful stained glass, to give the illusion of windows. The ceiling had been fitted with wooden beams, matching the wooden chairs, which were covered with large pillows. The decor and the seating made it look like more of an old church than a bar.

We chose a table directly in front of a small stage on which the band was assembling instruments. Judging by the bosoms protruding from the waitresses’ see-through outfits, it was clear what criteria had been used to hire them.

Soon the club was crowded. The air smelt of fermented ale. I felt so uncomfortable, I began to wonder about Zack’s judgment and my own.

Minutes later, several shots of tequila had cleared my larynx and forced my lungs to make peace with the smoke. But it was the voice of the tall dark African American woman belting the blues that finally made me forget the place was a danger to my health. Each note vibrated from her belly. She sang as if every word and gesture and hip motion mattered. Her voice took me on a journey to worlds of rainbow colors. Observing my fascination, Zack asked if I would like to meet her. “Really, you can make it happen?” I blurted.

After the performance, he took me to into a small bar backstage. We found the singer on a barstool, swiveling back and forth as she sipped mineral water from a bottle. She had changed from the stage maxidress into a white cotton shirt over skintight blue jeans tucked into knee-high platform boots.

“Melinda,” she said as she stretched out her long hand to greet me.

Up close, under neutral lighting, and without stage makeup, her big eyes and high cheekbones stood out. Her long straightened hair was still combed back, slightly covering her ears, from which hung her trademark, dangling gold earrings. Her dark skin looked smooth, like velvet, and her wide smile revealed a perfect set of white teeth.

“You are beautiful,” I said. “With a golden voice.”

“You are beautiful, too,” she returned the compliment, “but I can’t say anything about your voice, because I have not heard you sing.”

“Thank you,” I said. “I don’t have my mother’s voice. She was a singer. But she confined it to our local church.”

“Really? What a coincidence. My mother sang in church,” Melinda said. “I sing in the same choir sometimes.”

Just then a tall, broad-shouldered, light-skinned man appeared and growled something. I felt rather than saw Zack tense up.

“Meet Zack’s fiancée,” Melinda hastened to say, snapping the standoff between the men. “Mugure, this is my husband, Mark. He comes for me every night. Doesn’t trust the red lights.”

He smiled and shook my hand, nodding to Zack, almost. The change from near hostility to hospitality was fleeting but unmistakable.

We left. Zack let me know that he had dated Melinda for a few months during their college days at New York University. They had lost contact after graduation but, through sheer coincidence, met up again at Edward and Palmer Advocates, where she did some consulting.

“She’s a lawyer?” I said, even more amazed at her many talents.

“No, a financial analyst.”

“Who sings in nightclubs and churches?”

“Yes, but don’t underestimate her. She’s excellent with computers. Call her director of virtual reality,” he said, laughing.

“Fascinating,” I said. “How does she manage it?”

“With different names. Black Madonna for the club and Black Angel for the choir,” he said.

“And as financial analyst?” I asked.

“Meli Virtuoso,” he said. “But she plays herself. Melinda.”

“And Mark?”

“He’s Afro-Mexican but can easily pass for white. Extremely wealthy, humble beginnings, vast landscaping empire. He’s established a virtual monopoly in and around the tristate area. We’re friends, but he blows hot and cold. He can’t get past the fact that Melinda and I once dated. The fiancée thing was meant to reassure him.”

Despite the lighting and the smoke, or perhaps because of them and Melinda’s voice, Shamrock was addictive, and as Zack and I became lovers, we became regulars. Many people seemed to know Zack, and we saw quite a few on and off the dance floor.

That’s why I didn’t see it as odd when, one night, a gentleman in a dark suit bumped against us several times, with Zack deftly avoiding a collision. During the break, the suited gentleman left his partner, followed us to our table, and pulled out a chair. Then he casually took out a small gun from inside his jacket, put it on the table, and covered it with his large palms. Zack put a protective arm around me. I was speechless with terror; my eyes never left the gun.

“Of course you don’t know me, lawyer,” the man said calmly. “Remember the document, drawn and signed in this place?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Zack said in a level tone.

“But you do! I bring a message from the priest. He has been checking his bank accounts. No deposits lately. It will be a different message next time,” he finished, and without waiting for a response, he put the gun back in his jacket and vanished. It happened so quickly that for a second I thought he was an illusion.

“They don’t leave me alone. Sometimes they even follow me to the bathroom,” Zack said in a steady voice. “It’s the notoriety that comes with working for a prominent law firm.”

I was surprised by how calmly Zack had taken the incident, but it reassured me to hear him explain. A legal firm was like a church, prison, or hospital. You meet all sorts, they know you, you don’t know them, but you act as if you do: It’s called public relations. Sometimes they come with a grudge over an issue you have long since forgotten. Attorneys are in the same position as judges. A judge sentences a person and thinks that’s the end. The next time, a year, many years later, the criminal faces him with a knife or gun in a crowded marketplace or in a church. “You remember me?” the criminal asks. Of course the judge does not.

“The fact is, I have no clue what the man was about. Crazy. Or a case of mistaken identity. Forget it.”

• • •

Years later, scrambling for my life in the underbelly of the streets of Nairobi, I would often recall the incident and wonder why I didn’t take it as a warning and walk out of Zack’s life for good. Instead, the hint of danger and the den’s atmosphere of mellowing decadence proved hypnotic.

Besides, Zack came into my life when I most needed a lucky break. I had just earned my first degree from the City College of New York. For a while I tinkered with the idea of going back home to Kenya, but from what my lawyer friend Jane Kagendo told me, Nairobi streets were bustling with unemployed BAs. I stayed on in America, hoping to go to graduate school, though I did not have the money. With my student visa expired, I was caught up in the hide-and-hope-never-to-be-caught existence of an illegal immigrant. It’s a life lived underground, accepting any jobs, any wages, lying about one’s status even to fellow immigrants, tensing up at a knock on the door or the sight of police officers, always on a nervous edge in bed or on the street.

Although O&O paid me miserably, I stayed with the firm because the owner had promised he would help me get an H1 visa and eventually a green card. The other way to get a green card was to settle down with an American citizen, but my relationships were always short-lived.

The longest and latest was a two-year stint with Sam, a white American, the man from the banks of Ohio, as I used to call him, a commuter relationship sustained via email, Facebook, Internet chats, texting, and occasional sexting, though plagued with uncertainty: We would promise to meet up and talk about our future face-to-face, but whenever we did, we talked about everything else, and only after he had returned to Ohio or I to New York would I remember that we had skirted the issues of marriage and green cards. I broke it off—or, more truthfully, Zack made memories of that relationship fade into a land of it-never-happened. I did not even bother telling Zack about Sam.

Despite our different histories—he with family origins in Estonia, a former Soviet satellite, and I from Kenya, a former British colony—I felt that Zack and I complemented each other. He took control; I let him and felt safe in his certainty. He loved telling and retelling stories drawn from his life; I loved listening and talked little about events in my life.

Once, in a café on lower Broadway with David West, Zack’s childhood friend and now colleague at Edward and Palmer, I asked about the limp he carried so well walking or on the dance floor. Zack told a harrowing story of how he’d survived a hit-and-run; his left leg had to be reconstructed with the recovered pieces of his broken bones. David laughed and told a less dramatic version: Zack fell off his motorbike as the two raced each other. Zack was lucky to get away with a fracture and a slightly shorter leg after surgery. I was about to laugh good-humoredly at the different versions when I saw Zack stand up and look at David with cold steely eyes, hissing, “You say I’m lying?” David apologized and mumbled something about memory being unreliable. Zack sat down, smiled at me, and apologized to David for overreacting. Then he laughed, apparently at the absurdity of the situation. We joined the uneasy laughter.

The incident, or rather the steely look, should have given me pause. Instead, I moved into his Manhattan bachelor pad in the winter. In the summer, we moved to a plush home nestled in a cul-de-sac in an affluent neighborhood of Riverdale, on the northwest side of the Bronx. With its tree-lined streets and quaint mansions on gentle slopes, the area combined the best of city and country living. The backyard gave way to a small garden in which I immediately planted herbs and tomatoes. It was here in the garden, on a morning of sunshine with the music of a hummingbird from a nearby hedge, that he knelt and asked me to marry him. I accepted.

We celebrated our wedding, conducted by a justice of the peace in our backyard, with a dinner party for a few friends, among them Melinda, David, Joe, and Mark. The conspicuous absence of my own friends reflected how deeply I had lost contact with the African community abroad, and how unsocial I was in New York. Zack offered to fly in my friend Ciru Mbai, a researcher at Cape Town University in South Africa, but she declined because she was finishing her PhD dissertation. Jane Kagendo, whom I had known since our school days in Msongari, Kenya, accepted Zack’s offer of a ticket, but at the last minute she texted to say that she was in the middle of what she called “a weird and complicated case” involving some sort of alternative clinics and could not make it. Zack wondered what I knew of these clinics that would keep my friends away, but I had no clue what Jane was talking about and assured him he would meet her one day.

I brushed off the disappointment. I was too happy to let anything bring me down. The evening started quietly, but as it wore on, and aided by a few drinks, my guests became animated. Their stories revolved around themes of marriage: vows of sickness and health till death do us part, that kind of thing. David told of an inseparable Bronx couple with a nose for the latest gossip about any- and everyone in the Bronx. Though they were husband and wife, they were more like twins.

“But they are twins,” Zack interjected, heightening our interest in the ubiquitous couple. He waited for a few seconds, savoring our curiosity. “They are designer twins,” he said, explaining that the pair had renewed themselves through cloned body parts grown to their specifications.

This raised cries of no, no, some arguing that despite the 1996 case of Dolly, technology had not reached a level to make a human out of cloned body parts. David, who may have learned not to contradict Zack, said that while it was possible, it seemed to him that the pair had simply taken on each other’s personality. “That’s what long life can do to a loving couple,” he said, looking in the direction of Zack and me.

Not to be outdone, Mark (whose tongue had been loosened by quite a few Jacks on the rocks), let everybody know that he was rich enough to buy immortality. He talked of his success and publicly invited Zack and Joe and everybody else to join him on new business ventures abroad. He was fascinated with Africa and saw many opportunities, he said, looking at me, as if I were somehow a confirmation.

By contrast, Joe, who owned a real estate company in wealthy Fairfield County, Connecticut, did not utter a word about his worth. He believed in man and woman’s immortality of joy in bed only, he joked, winking at Zack and me.

Melinda sang my favorite Dusty Springfield song: The only one who could ever reach me was the son of a preacher man. Granted, Zack was no preacher’s son, but the song was also about finding love in the most unexpected way. It was a special treat for me.

After the song, Mark embraced Melinda and looked around, as if to say, She’s mine. Joe told her that if she ever got tired of Mark, he would be waiting in the wings, his way of paying a compliment. Joe’s incessant flirting and endless compliments, which Melinda accepted with a smile that invited more, may have done it: Mark and Melinda were the first to leave, he literally dragging her away.

Years later, alone in my bed at night, I would go over every word uttered; examine every gesture and facial expression; recall the stories and the laughter, trying to find a piece that would point me to the Lucifer among the angels who celebrated my marriage to Zack that night.

1

My cell phone rang. I assumed it was from Detective Ben Underwood again. I looked at the backseat, where my son, Kobi, excitedly cradled his soccer ball; he had scored the winning goal for his side. I answered the phone and asked, “Hey, got more details?”

I heard muffled noise followed by shallow breathing. I took the phone from my ear and checked the caller ID. PRIVATE, it read. It was not Ben.

“Hello . . . Hello?”

No answer. I hung up. It rang again. The same muffled noise.

“What do you want?” I asked, irritated, thinking it was a telemarketer.

“Take this from a friend,” said a deep voice in a put-on Jamaican accent. “You ask too many questions.”

“Who are you?”

“Just stop it.” And the line went dead.

I looked around the car in panic. I instinctively reached out to Kobi, to reassure him, but more myself. He had been through enough in his journey into our lives. But of course only I heard the threat. My hands were shaking. Compose yourself, Mugure. There is nothing to this. A crank call.

I dialed Ben and went over every detail of what had just taken place.

“Are you sure?” he asked.

I felt irritated by his question. “Think I’m making it up?”

“No, no,” Ben protested, and told me to let him know if the person called again. “But, Mugure, be careful,” he said before he hung up.

I was relieved when Kobi and I found Zack at home. Everything appeared normal again. But I sensed something had come undone.

• • •

I first met my husband, Zack, at the office of Okigbo & Okigbo, a law firm in Manhattan, on Canal Street, not far from south Broadway. Actually, the firm was not a partnership, but the double-barreled title made the sole proprietorship appear bigger and more powerful. I was coming from the bathroom back to the reception desk when I literally walked into Zack. His papers went flying all over the corridor.

“Body screening?” he said as I quickly ran about, collecting the papers.

I brought them back, trying to align them, and came face-to-face with a tall, preppy, but strikingly good-looking blond man. He almost let the papers fall again as he frowned and gave me a long hard look. Disapproval, I thought.

“I am really sorry, sir,” I managed with a sheepish smile.

“I should sue you for invading my privacy,” he said. In what seemed a quick afterthought, he added, “But a cup of coffee would make me forget this ever happened.”

“Sounds like a plan,” I said without thinking, but then I would have said anything to end the embarrassment.

He had come to meet with my boss for a deposition in a case of medical malpractice. I pointed in the direction of Mr. Okigbo’s office. He didn’t budge. He continued standing there, as if studying me.

“Umm . . . your number,” he said at last.

“Oh, yes, of course, one second, sir. If you can come this way, please,” I said, leading him toward Okigbo’s office, fumbling in my bag for a card, anything to get him away.

“Mugure. Office manager,” he said, glancing at the card.

I hoped he was not being sarcastic about the pretentious title. I was a part-time receptionist and a glorified all-purpose messenger. To complete “all-purpose” for the same wages, Okigbo wanted to have me trained as an armed security guard and even had me go to a shooting range. When my eyes closed and my hands trembled involuntarily at the sight of a gun, my would-be trainer returned a verdict of hopeless that ended whatever security ambitions Okigbo had in store for me.

“Zack Sivonen,” he said, “Edward and Palmer Advocates,” which was unnecessary because the name and its location, in lower Manhattan, were on the card he gave me. He entered Mr. Okigbo’s office. I noticed that he walked with a slight limp, but it suited him, as if it were a style he had cultivated.

On our first date, Zack took me to Shamrock, a club in the basement of a sex shop on Forty-Second Street between Sixth and Eighth Avenues, the red-light district of New York City. Blue fluorescent bulbs lit our descent into a dungeon. Even when the lighting changed into a clearer soft yellow, the atmosphere remained eerie, as in a horror film. The ambient smoke made me cough.

“It gets better, I promise,” Zack said, noting my discomfort.

“I sure hope so,” I said.

I began to make out the outlines of things. One section of the wall was decorated with colorful stained glass, to give the illusion of windows. The ceiling had been fitted with wooden beams, matching the wooden chairs, which were covered with large pillows. The decor and the seating made it look like more of an old church than a bar.

We chose a table directly in front of a small stage on which the band was assembling instruments. Judging by the bosoms protruding from the waitresses’ see-through outfits, it was clear what criteria had been used to hire them.

Soon the club was crowded. The air smelt of fermented ale. I felt so uncomfortable, I began to wonder about Zack’s judgment and my own.

Minutes later, several shots of tequila had cleared my larynx and forced my lungs to make peace with the smoke. But it was the voice of the tall dark African American woman belting the blues that finally made me forget the place was a danger to my health. Each note vibrated from her belly. She sang as if every word and gesture and hip motion mattered. Her voice took me on a journey to worlds of rainbow colors. Observing my fascination, Zack asked if I would like to meet her. “Really, you can make it happen?” I blurted.

After the performance, he took me to into a small bar backstage. We found the singer on a barstool, swiveling back and forth as she sipped mineral water from a bottle. She had changed from the stage maxidress into a white cotton shirt over skintight blue jeans tucked into knee-high platform boots.

“Melinda,” she said as she stretched out her long hand to greet me.

Up close, under neutral lighting, and without stage makeup, her big eyes and high cheekbones stood out. Her long straightened hair was still combed back, slightly covering her ears, from which hung her trademark, dangling gold earrings. Her dark skin looked smooth, like velvet, and her wide smile revealed a perfect set of white teeth.

“You are beautiful,” I said. “With a golden voice.”

“You are beautiful, too,” she returned the compliment, “but I can’t say anything about your voice, because I have not heard you sing.”

“Thank you,” I said. “I don’t have my mother’s voice. She was a singer. But she confined it to our local church.”

“Really? What a coincidence. My mother sang in church,” Melinda said. “I sing in the same choir sometimes.”

Just then a tall, broad-shouldered, light-skinned man appeared and growled something. I felt rather than saw Zack tense up.

“Meet Zack’s fiancée,” Melinda hastened to say, snapping the standoff between the men. “Mugure, this is my husband, Mark. He comes for me every night. Doesn’t trust the red lights.”

He smiled and shook my hand, nodding to Zack, almost. The change from near hostility to hospitality was fleeting but unmistakable.

We left. Zack let me know that he had dated Melinda for a few months during their college days at New York University. They had lost contact after graduation but, through sheer coincidence, met up again at Edward and Palmer Advocates, where she did some consulting.

“She’s a lawyer?” I said, even more amazed at her many talents.

“No, a financial analyst.”

“Who sings in nightclubs and churches?”

“Yes, but don’t underestimate her. She’s excellent with computers. Call her director of virtual reality,” he said, laughing.

“Fascinating,” I said. “How does she manage it?”

“With different names. Black Madonna for the club and Black Angel for the choir,” he said.

“And as financial analyst?” I asked.

“Meli Virtuoso,” he said. “But she plays herself. Melinda.”

“And Mark?”

“He’s Afro-Mexican but can easily pass for white. Extremely wealthy, humble beginnings, vast landscaping empire. He’s established a virtual monopoly in and around the tristate area. We’re friends, but he blows hot and cold. He can’t get past the fact that Melinda and I once dated. The fiancée thing was meant to reassure him.”

Despite the lighting and the smoke, or perhaps because of them and Melinda’s voice, Shamrock was addictive, and as Zack and I became lovers, we became regulars. Many people seemed to know Zack, and we saw quite a few on and off the dance floor.

That’s why I didn’t see it as odd when, one night, a gentleman in a dark suit bumped against us several times, with Zack deftly avoiding a collision. During the break, the suited gentleman left his partner, followed us to our table, and pulled out a chair. Then he casually took out a small gun from inside his jacket, put it on the table, and covered it with his large palms. Zack put a protective arm around me. I was speechless with terror; my eyes never left the gun.

“Of course you don’t know me, lawyer,” the man said calmly. “Remember the document, drawn and signed in this place?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Zack said in a level tone.

“But you do! I bring a message from the priest. He has been checking his bank accounts. No deposits lately. It will be a different message next time,” he finished, and without waiting for a response, he put the gun back in his jacket and vanished. It happened so quickly that for a second I thought he was an illusion.

“They don’t leave me alone. Sometimes they even follow me to the bathroom,” Zack said in a steady voice. “It’s the notoriety that comes with working for a prominent law firm.”

I was surprised by how calmly Zack had taken the incident, but it reassured me to hear him explain. A legal firm was like a church, prison, or hospital. You meet all sorts, they know you, you don’t know them, but you act as if you do: It’s called public relations. Sometimes they come with a grudge over an issue you have long since forgotten. Attorneys are in the same position as judges. A judge sentences a person and thinks that’s the end. The next time, a year, many years later, the criminal faces him with a knife or gun in a crowded marketplace or in a church. “You remember me?” the criminal asks. Of course the judge does not.

“The fact is, I have no clue what the man was about. Crazy. Or a case of mistaken identity. Forget it.”

• • •

Years later, scrambling for my life in the underbelly of the streets of Nairobi, I would often recall the incident and wonder why I didn’t take it as a warning and walk out of Zack’s life for good. Instead, the hint of danger and the den’s atmosphere of mellowing decadence proved hypnotic.

Besides, Zack came into my life when I most needed a lucky break. I had just earned my first degree from the City College of New York. For a while I tinkered with the idea of going back home to Kenya, but from what my lawyer friend Jane Kagendo told me, Nairobi streets were bustling with unemployed BAs. I stayed on in America, hoping to go to graduate school, though I did not have the money. With my student visa expired, I was caught up in the hide-and-hope-never-to-be-caught existence of an illegal immigrant. It’s a life lived underground, accepting any jobs, any wages, lying about one’s status even to fellow immigrants, tensing up at a knock on the door or the sight of police officers, always on a nervous edge in bed or on the street.

Although O&O paid me miserably, I stayed with the firm because the owner had promised he would help me get an H1 visa and eventually a green card. The other way to get a green card was to settle down with an American citizen, but my relationships were always short-lived.

The longest and latest was a two-year stint with Sam, a white American, the man from the banks of Ohio, as I used to call him, a commuter relationship sustained via email, Facebook, Internet chats, texting, and occasional sexting, though plagued with uncertainty: We would promise to meet up and talk about our future face-to-face, but whenever we did, we talked about everything else, and only after he had returned to Ohio or I to New York would I remember that we had skirted the issues of marriage and green cards. I broke it off—or, more truthfully, Zack made memories of that relationship fade into a land of it-never-happened. I did not even bother telling Zack about Sam.

Despite our different histories—he with family origins in Estonia, a former Soviet satellite, and I from Kenya, a former British colony—I felt that Zack and I complemented each other. He took control; I let him and felt safe in his certainty. He loved telling and retelling stories drawn from his life; I loved listening and talked little about events in my life.

Once, in a café on lower Broadway with David West, Zack’s childhood friend and now colleague at Edward and Palmer, I asked about the limp he carried so well walking or on the dance floor. Zack told a harrowing story of how he’d survived a hit-and-run; his left leg had to be reconstructed with the recovered pieces of his broken bones. David laughed and told a less dramatic version: Zack fell off his motorbike as the two raced each other. Zack was lucky to get away with a fracture and a slightly shorter leg after surgery. I was about to laugh good-humoredly at the different versions when I saw Zack stand up and look at David with cold steely eyes, hissing, “You say I’m lying?” David apologized and mumbled something about memory being unreliable. Zack sat down, smiled at me, and apologized to David for overreacting. Then he laughed, apparently at the absurdity of the situation. We joined the uneasy laughter.

The incident, or rather the steely look, should have given me pause. Instead, I moved into his Manhattan bachelor pad in the winter. In the summer, we moved to a plush home nestled in a cul-de-sac in an affluent neighborhood of Riverdale, on the northwest side of the Bronx. With its tree-lined streets and quaint mansions on gentle slopes, the area combined the best of city and country living. The backyard gave way to a small garden in which I immediately planted herbs and tomatoes. It was here in the garden, on a morning of sunshine with the music of a hummingbird from a nearby hedge, that he knelt and asked me to marry him. I accepted.

We celebrated our wedding, conducted by a justice of the peace in our backyard, with a dinner party for a few friends, among them Melinda, David, Joe, and Mark. The conspicuous absence of my own friends reflected how deeply I had lost contact with the African community abroad, and how unsocial I was in New York. Zack offered to fly in my friend Ciru Mbai, a researcher at Cape Town University in South Africa, but she declined because she was finishing her PhD dissertation. Jane Kagendo, whom I had known since our school days in Msongari, Kenya, accepted Zack’s offer of a ticket, but at the last minute she texted to say that she was in the middle of what she called “a weird and complicated case” involving some sort of alternative clinics and could not make it. Zack wondered what I knew of these clinics that would keep my friends away, but I had no clue what Jane was talking about and assured him he would meet her one day.

I brushed off the disappointment. I was too happy to let anything bring me down. The evening started quietly, but as it wore on, and aided by a few drinks, my guests became animated. Their stories revolved around themes of marriage: vows of sickness and health till death do us part, that kind of thing. David told of an inseparable Bronx couple with a nose for the latest gossip about any- and everyone in the Bronx. Though they were husband and wife, they were more like twins.

“But they are twins,” Zack interjected, heightening our interest in the ubiquitous couple. He waited for a few seconds, savoring our curiosity. “They are designer twins,” he said, explaining that the pair had renewed themselves through cloned body parts grown to their specifications.

This raised cries of no, no, some arguing that despite the 1996 case of Dolly, technology had not reached a level to make a human out of cloned body parts. David, who may have learned not to contradict Zack, said that while it was possible, it seemed to him that the pair had simply taken on each other’s personality. “That’s what long life can do to a loving couple,” he said, looking in the direction of Zack and me.

Not to be outdone, Mark (whose tongue had been loosened by quite a few Jacks on the rocks), let everybody know that he was rich enough to buy immortality. He talked of his success and publicly invited Zack and Joe and everybody else to join him on new business ventures abroad. He was fascinated with Africa and saw many opportunities, he said, looking at me, as if I were somehow a confirmation.

By contrast, Joe, who owned a real estate company in wealthy Fairfield County, Connecticut, did not utter a word about his worth. He believed in man and woman’s immortality of joy in bed only, he joked, winking at Zack and me.

Melinda sang my favorite Dusty Springfield song: The only one who could ever reach me was the son of a preacher man. Granted, Zack was no preacher’s son, but the song was also about finding love in the most unexpected way. It was a special treat for me.

After the song, Mark embraced Melinda and looked around, as if to say, She’s mine. Joe told her that if she ever got tired of Mark, he would be waiting in the wings, his way of paying a compliment. Joe’s incessant flirting and endless compliments, which Melinda accepted with a smile that invited more, may have done it: Mark and Melinda were the first to leave, he literally dragging her away.

Years later, alone in my bed at night, I would go over every word uttered; examine every gesture and facial expression; recall the stories and the laughter, trying to find a piece that would point me to the Lucifer among the angels who celebrated my marriage to Zack that night.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (February 17, 2015)

- Length: 288 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476760339

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Fall of Saints Trade Paperback 9781476760339

- Author Photo (jpg): Wanjiku wa Ngugi Photograph by Sami Sallinen(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit