Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

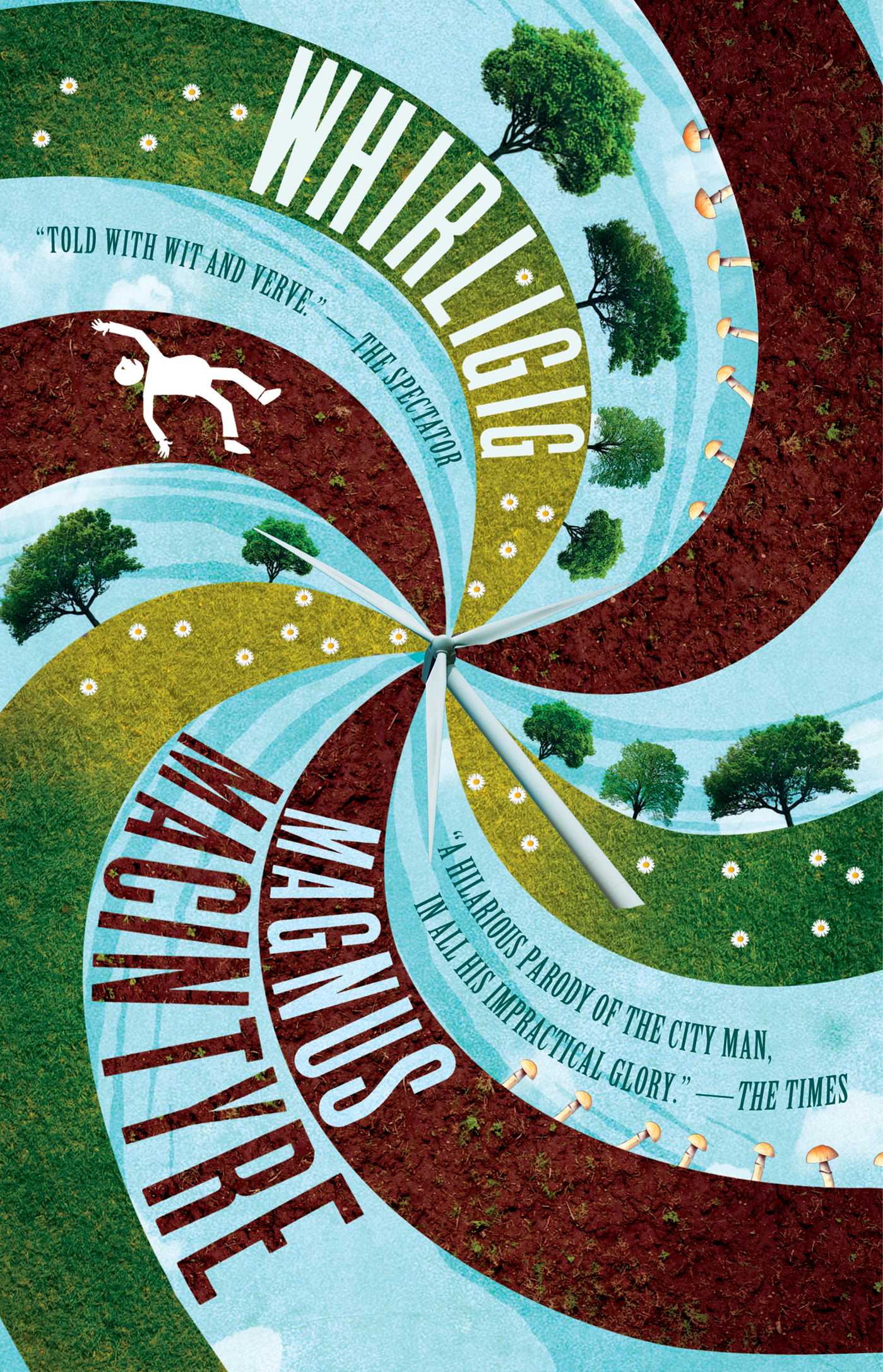

A mid-life crisis comedy that sees a city man drop everything to move to the country, a hilarious parody of city life that is also a deeply felt celebration of wild Scotland, responsible capitalism and the redemptive power of nature.

Claypole is not ‘a large man’. He is a fat man. A fat man with thin limbs, like an egg with tentacles. And life is not going well. He’s alone, idle, and on the brink of a medical crisis when a childhood acquaintance makes him an offer he can’t understand, can’t talk about, but ultimately can’t refuse.

A week later, he finds himself in the wilds of Scotland, plunged into an eccentric community at war over a wind farm. And he’s supposed to be a backer, but he has no idea what side he’s on, even though it may bag him a lot of money. All he wants is to look like a hero in front of the woman with the bright blue eyes who brought him here. To do so he must run the gauntlet of a family with many dark secrets, some dangerous hippies and their hallucinogenic potions, and the wilderness itself with all its threats and dangers.

Whirligig is a raucous, joyous, often poignant comedy about the redemptive power of the countryside. Written with peerless wit, it’s a timely fable that takes its place within the tradition of the Great English Comic Novel. It’s The Wicker Man as told by P.G. Wodehouse.

Claypole is not ‘a large man’. He is a fat man. A fat man with thin limbs, like an egg with tentacles. And life is not going well. He’s alone, idle, and on the brink of a medical crisis when a childhood acquaintance makes him an offer he can’t understand, can’t talk about, but ultimately can’t refuse.

A week later, he finds himself in the wilds of Scotland, plunged into an eccentric community at war over a wind farm. And he’s supposed to be a backer, but he has no idea what side he’s on, even though it may bag him a lot of money. All he wants is to look like a hero in front of the woman with the bright blue eyes who brought him here. To do so he must run the gauntlet of a family with many dark secrets, some dangerous hippies and their hallucinogenic potions, and the wilderness itself with all its threats and dangers.

Whirligig is a raucous, joyous, often poignant comedy about the redemptive power of the countryside. Written with peerless wit, it’s a timely fable that takes its place within the tradition of the Great English Comic Novel. It’s The Wicker Man as told by P.G. Wodehouse.

Excerpt

Whirligig -1-

With Death comes honesty.

The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie

Pink’s, like many of the white-stuccoed buildings of St James’s, is a private members’ club. Some regard these clubs as not so much ‘private’ as ‘secret’, and certainly there are only two facts about Pink’s which appear in the public domain. The first is that the club has recently inherited the bulk of the estate of the artist James Hoogstratten, R.A. This ran into millions, and the club’s members have voted not to take the £30,000 each that they were due by the club’s constitution. Instead, they ploughed the entire windfall into boosting the quality and size of Pink’s wine cellar, and in acquiring van Gogh’s The Beech Tree, which now hangs modestly at the bottom of the main staircase. The second fact that is known about Pink’s is its strict dress code.

Wearing a suit and tie, in most lines of work these days, is a clear sign of a lack of seniority. But few men make the mistake of turning up at Pink’s without the requisite garb. If they did they would be subjected to the special torture of being forced to wear something the club provided. This would be a jacket that bordered on fancy dress, and a tie of such luridness and unfashionability that it could only be worn by a fringe comedian, or a castaway looking to be seen from 35,000 feet.

There are many rules in Pink’s. Many similar clubs have banned the use of mobile telephones, but Pink’s also bans trousers without a crease, soft shoes, collarless shirts, children, personal computers, and the wearing of hats and swords beyond the cloakroom. Pink’s considers itself rather avant-garde for having lifted – over ten years ago – its 240-year ban on women becoming members. But judging by the members present on the average hazy August afternoon, this happy news seems not yet to have been passed on to any actual women.

Peregrine MacGilp of MacGilp, one such member on one such afternoon, was perpetually irritated to have to smoke his cigarettes while standing in the street. But he used his time in the smoggy sunshine productively by simultaneously puffing and conducting an exchange of text messages with his niece. They had business to discuss.

‘Lawyer phoned,’ said the first incoming text. ‘We only have a week. GC is realistically our last chance.’

Peregrine replied, thumbing the buttons on his phone with hesitancy, hindered by long-sightedness and lack of expertise. ‘WILCO. REMINT ME WHAT WE NKOW OF GC?’

A minute later, his phone buzzed with another message. ‘Rumour is he sold biz for big ££. Some sort of tech/media thing.’

Peregrine decided to tease his niece. ‘GOLD-LOOKING, IS HE? ALL YOUR FRIENDS ARE. TALL TOO, I SUPPORT.’

‘Haven’t seen him since we were kids,’ replied the niece, ignoring the predictive text problems. ‘Might be Scottish?’

Peregrine texted back. ‘SOUND LIKE A MATTER OF THE UNIVERSE TYPE. BUSINESSMEN LIKE STRAIGHT TANKING. SHALL JUST BE MYSELF.’

It was just twenty seconds before the final communication.

‘Strongly advise you not to.’

Smiling, but with a wrinkled brow, Peregrine tucked his phone away in a well-tailored pocket. He did not generally meet high-powered entrepreneurs, and was unaccustomed to business meetings in which he was not the one being sold to. He inhaled deeply on the remainder of his cigarette. But Peregrine would deal with this challenge as he did all others in life, by assuming that things would probably work out for the best. They always did. So he went back inside his club, there to order a pot of Russian Caravan, and put to the back of his mind the feeling that he would rather his niece were joining him for this meeting on which his fate, and the fate of many others, would be determined.

As Peregrine waited patiently for his tea, the man he was due to meet was standing just a hundred yards away on Piccadilly, sweating at his reflection in the broad window of an expensive shop.

Gordon Claypole was tubby, and only in the thorax. His short legs and arms, over which he had only limited control, were thin and weak. He was not ‘a large man’. He was a fat man. This saddened him not just because of its genetic inevitability and the echo of his long-dead father, but because, having been a fat child, he had briefly been a normal-shaped young adult. At thirty-five, he was once again an egg with tentacles, and wished that he had never known what it was like to look anything other than odd. There was always something in his reflection to admonish, and inflict the persistent pain that, he supposed, dogs all people who are physically inadequate. He stared more closely at his reflection. Sometimes it was the beetroot bags under his eyes that struck him as ugly, sometimes the reddening bulb of a nose, or the collection of grey-green chins that hung from his jaw like stuffed shopping bags. Today, though, it was his oyster eyes and their network of scarlet veins that disgusted him. He also found time to loathe the dyed black hair that was losing the battle for influence over his huge potato of a head. And in these clothes – black suit, white shirt, black tie – he thought the entire ensemble gave him the appearance of a ghoulish and hard-living undertaker.

‘Fuck it,’ he burbled idly to his reflection as he stumbled on from the shop front and felt an ache in his chest.

Claypole was familiar with the other kind of private members’ club. The sort that spring up like dandelions, and very often disappear again as quickly, from the streets of Soho. A short stroll from St James’s, but a world away, the most octane-fuelled of the capital’s media workers and their hangers-on collide in these other haunts on weeknights, bitching, bragging, gossiping and flirting, getting quickly drunk and lording it shrilly over the waiting staff. The older ones are tired and lonely, with the resources to destroy careers, egos or emotions as they choose. The younger ones fight among themselves for position, or fame, or money, and possess the joint characteristics of overconfidence and desperation, a combination only otherwise found in lesser-league football. Only the lucky few, for all the talk, find a decent price for their souls.

So, like Lewis Carroll’s Alice trying to adjust to a new world, Claypole rubbed his eyes as he stepped through the small eighteenth-century door to Pink’s. The size of the entrance belied the club’s vast interior. It was stunning, too, in a faded sort of way. Like an ancient screen actress, it had former glory as an all-pervading memory, and it could not but impress even if it gave the impression that it no longer cared to do so. Shifting silently about, the members were, like the cool dark interior, old and rich. These men, in their fine suits, had never doubted their position and never wanted for anything. If these souls were for sale at all, they would be very expensive.

Claret-coloured and puffing from the walk, Claypole announced his presence to the moustachioed and liveried man at the front desk. Clearly ex-military, the man gave Claypole the same look of disdain bordering on disgust he gave all non-members. This was the look that allowed the club to charge its members a thousand pounds a year in membership fees. They didn’t want ever to receive that look again. They wanted the other look the ex-military man gave, to members only: a slight but intensely respectful nod.

Moving slowly behind the ex-military gent into the main library, Claypole stiffened. He was trying to give himself the same air of unfettered, world-owning confidence he could feel coming from the members as they flicked through the pages of the Daily Telegraph, or coughed discreetly into a Scotch and soda. But he did not feel at home. A thousand pounds was what it cost you to belong, although it was a fee you got to pay only if you already belonged.

Using the arm of the old leather sofa for leverage, Peregrine MacGilp rose to an imposing six foot two. His silver hair, just a little long and fuzzy at the back but with a thick and immaculate quiff at the front, topped a remarkably unlined and square-set face. He looked like a Serbian war criminal in a burgundy corduroy suit and navy-blue sweater, but with boyishly excited eyes. Peregrine was the sort of old man – seventy, maybe, but with the gait of a fifty-year-old – that could grace a luxury yacht brochure until he was ninety. Claypole would become the other kind of old man – a structureless, cushiony wheezer with a baked-bean head. Claypole, should he still be alive at seventy, might look at home in the ticket booth of a funfair.

‘My dear fellow,’ said Peregrine in an immense baritone, stretching out a muscular arm and bristling with welcome.

‘Hi,’ said Claypole, and shook the old man’s hand, but held his gaze for only the briefest of moments.

‘Gordon, isn’t it?’ asked Peregrine.

‘Just Claypole,’ muttered Claypole, and gave him a challenging look. Peregrine smiled.

‘Gosh. You mean you don’t use your first name?’

‘People just call me Claypole.’

‘Oh… how marvellous!’ Peregrine clapped his hands with delight. ‘Like that left-wing chap with the dark glasses. What’s his name? Bonzo.’

‘Bono. Yeah,’ said Claypole, narrowing his eyes.

‘That’s the fellow,’ said Peregrine gaily, clicking his fingers. ‘Or Plato, I suppose. He’s only got one name, hasn’t he? Or Liberace.’ He smiled at Claypole with icy grey eyes, and added with unselfconscious non sequitur, ‘What fun.’

‘Brr.’ Claypole cleared his throat, as he did habitually in company, like a man who has swallowed a sizeable fly but doesn’t want anyone to know about it.

‘Do have a pew,’ said Peregrine, looking pleased and preparing to sit down. ‘Do you fancy some tea?’

They both looked at a prissy brilliantined midget in a white mess jacket, who had appeared at Claypole’s elbow.

‘No, thanks,’ said Claypole.

‘Really? Or some sandwiches? Or something else? They have pretty much anything here… It was at that table over there that my grandfather once ate a record number of oysters, but, ah… A snorter, perhaps? Bit early to start opening the pipes, but be my guest if you…’

Claypole watched a nearby codger in a light-blue blazer being served something lurid involving prawns, avocado and aspic.

‘Nah. Brr. Let’s get on with it,’ said Claypole, and barrelled himself into a red leather sofa opposite Peregrine. His intention – to make a proprietory gesture – was undermined somewhat by the fact that he bounced perilously on the unexpectedly well-sprung seat. Peregrine sat slowly, still smiling magnificently. They exchanged small talk as Claypole rehearsed to himself the chain of events that had led him to this place at this time.

Claypole had thirty-four Facebook friends. So when Peregrine’s niece, Coky Viveksananda, who had 196 Facebook friends, requested to become number 35 some months previously, he was in no position to turn her down. She assured him in her message that their parents had known each other many years ago, and that they had met as children. He accepted her request and replied that indeed he remembered her, which he did not, and then examined her Facebook profile. There was a picture of a petite girl in shades, possibly of southern Asian origin, sitting on a lawn somewhere and smiling shyly. Her friends had names like Max von Strum and Felicia Hungerford and appeared to Claypole to be either smug or vacuous. But she listed her hobbies as ‘necromancy and darts’, and her job as ‘Brigadier-General of Starfleet Command’, and gave no other personal details, showing an amused disdain for the social networking medium that Claypole admired but could not bring himself to exhibit. No other communication had occurred between them until three days previously. Coky wondered – in a pleasantly un-pushy message – if he would be interested in meeting her uncle in regard to a business opportunity. So here he was, sitting opposite the laird of a desolate estate on the west coast of Scotland consisting of a bleak and bulky Gothic revival house, a few chilly cottages and a considerable chunk of… apparently nothing very much, according to its squire.

‘Bugger all. It’s useless,’ said Peregrine, with simple sincerity. ‘The Loch Garvach estate is some of the worst land in Europe. Three thousand acres of good-for-nothing floating bog.’

Claypole was surprised. He thought everywhere was used for something.

‘Oh yes, indeed,’ added Peregrine, driving home the point. ‘You can’t even walk on most of it.’

‘Brr.’ This was Claypole giving his usual cough, but this time it was nearly a laugh. Peregrine himself laughed unashamedly. It was loud, deep and used his full throat, even a bit of tongue.

‘So what have you been up to, then? What keeps Gordon – sorry, Claypole – out of the alehouses?’

Claypole seemed to study his hands for a moment before speaking.

‘I’ve been in the pre-school entertainment biz. Brr. Multimedia…’ Claypole drummed the fingers of one hand on the other. ‘I realised that phone Apps was the way to go. It’s happened in everything. And I had this bunch of content – movies and text – which I converted to a kick-ass App. Content’s about communities and fans these days, not…’

Peregrine was looking at him with bewilderment. ‘By “movies”, do you mean films?’

‘Er… yeah.’

‘American films?’

‘No, just films. Cartoons,’ said Claypole, blushing. ‘Cathy the Cow, then Colin the Calf.’

Peregrine squinted. ‘And by “text”, you mean books?’

‘Yeah.’

‘For children?’

‘Pre-school. Yeah.’

‘Babies, in fact?’

‘Er… yeah.’

‘Right-oh…’ Peregrine’s incomprehension was not reduced. ‘I have a mobile telephone, of course. But – and call me a Luddite if you must – I want it to… well, be a phone. Not another blasted computer!’ Peregrine chuckled.

Claypole beheld the older man, eyeing him intensely. Here was the grinning MacGilp of MacGilp (for what possible reason could a man need the same name twice?), completely contented, and utterly comfortable. Clearly he had been given the best that being British can offer. White, male and probably Protestant, yes. But also extremely privileged, classically educated, landed and moneyed, with the teeth of an Arab stallion. He seemed to be oblivious to modernity and more or less indifferent to the opinion of others. You couldn’t learn to be like that, thought Claypole. You had to be born in the right place at the right time, and to the right people.

‘Anyway,’ Claypole concluded. ‘Brr. I sold the company a month ago.’

‘So you’re free?’ asked Peregrine.

Claypole sat back in his chair, and did his best Cheshire Cat.

‘Well done,’ said Peregrine, in a matter-of-fact way. ‘I had a job in the City once, but I didn’t understand it. Ballsed it up. If I hadn’t inherited a fair chunk of lolly, God knows where I’d be.’

‘Thanks,’ muttered Claypole, chewing his jaw.

‘Shall I talk a little about my proposition?’ asked Peregrine freshly.

‘Sure,’ said Claypole. ‘It’s… er, making electricity from wind, right?’ He watched the midget in the mess jacket glide past and regretted that he had not ordered a plate of cakes, or a pie. Peregrine leaned forward and explained the history of wind farming at Loch Garvach.

Two years previously, a company called Aeolectricity had paid Peregrine a small amount of money in the expectation that when the wind farm received approval from the planning authorities and was subsequently built and generating electricity, they would pay him a handsome annual rent. The gamble for Aeolectricity was that if planning permission were not granted, they would lose their investment. On the other hand, if successful, it would make them many millions over the twenty-five-year life of the wind farm. But Aeolectricity had gone bust even though almost all the work had been done, and the whole project now belonged to Peregrine. This had all happened in the last couple of months, and the planning committee of the local council was now due to make its decision on whether the wind farm could go ahead or not.

‘It’s madness,’ began Peregrine in conclusion. ‘Why they leave it to the little people to make these decisions, I really don’t know. This and that sub-committee of Mr and Mrs McIdiot. They haven’t got a clue about how to plan a power station. Why would they? They’re not experts in anything very much, and they’re certainly not experts in this.’

Peregrine finished his monologue and his grey eyes flashed at Claypole. ‘Still. Pretty golden, eh?’

‘Right, yeah,’ said Claypole, looking across at the man in the light-blue blazer, who appeared to be falling asleep in front of his avocado mess. ‘So you need money?’

‘We need, more than anything else, a backer.’ Peregrine smiled. ‘A serious person. An homme d’affaires, if you like. Unpaid for the moment, but heavily rewarded if we’re successful.’

This evasion, Claypole knew instantly, spelled danger. Everyone needed money.

‘How much do you need?’ asked Claypole, in as bald a manner as he could manage.

‘As I say, it’s not so much the money…’

‘Yeah,’ said Claypole, closing his eyes with irritation in the manner he had seen done by business hotshots on television when faced with yet another common-or-garden mendacious incompetent. ‘How much do you need?’

‘I really don’t want your money, old chap,’ said Peregrine, not letting up with his smile. ‘I just need you to stand up in front of the powers that be and give them a bit of the old razzle-dazzle.’

‘Brr,’ said Claypole. ‘You really think the plan stacks up? Profit-wise?’

‘Oh yes. It’s a gold mine. Thanks to the government.’

‘There are government grants?’

‘Not quite. It’s cleverer than a straight hand-out.’ Peregrine leaned forward conspiratorially. ‘Because of these global warming do-dahs – you know, Britain has to reduce our carbon whatsits by such-and-such – anyone who has a wind farm can charge more for their electricity than someone with a coal-fired power station, or gas or whatever. A lot more. And there’s a lot of other financial how’s-your-fathers that make it even more attractive.’

Claypole scratched his nose.

‘Speaking personally,’ Peregrine continued, ‘I’m not absolutely convinced that there is such a thing as global warming… Doesn’t matter what I think, of course. Everyone else seems to think it’s important, and so do the powers that be. It’s the law.’ Peregrine looked around him for spies. ‘Don’t tell my niece that I don’t really believe in global warming, will you? She’s a fervent believer.’

‘Brr,’ said Claypole, attempting inscrutability. ‘But Loch Garvach is windy, yeah?’

‘Oh yes. Frightfully windy,’ said Peregrine.

‘Blow your hat off?’ suggested Claypole.

‘Blow your face off,’ corrected Peregrine. ‘Honestly, it would carry you off to Ireland.’ Then Peregrine was suddenly grave. ‘If the wind were an easterly… which it rarely is.’

‘Right,’ said Claypole, also suddenly serious.

They fell silent for a moment. The old man in the light-blue blazer was slipping further towards his plate of avocado and prawn, and Claypole wondered whether he should alert someone.

‘Do you go back to Scotland much?’ asked Peregrine.

‘Nah. Haven’t been there for years. Used to go on holiday there till Granny died. I stay put in London mostly. Spain for holidays.’

Peregrine sniffed the air. ‘Ah yes. Italia para nacer, Francia para vivir, España para morir. And of course you can’t beat the dear old Prado.’

The two men stared into the middle distance, remembering their respective Spanish holidays. Of the two of them, only Claypole could see how different those memories would be. Peregrine, a floozy named Minty or Bella in tow, probably drank delicious rosé with cravat-wearing Spanish nobility in the olive groves of delightfully dilapidated castles. To date, Claypole’s solo holidays had consisted of sleeping in the burning sun on plastic deckchairs next to tattooed plumbers from Brentwood with brattish children, and then trying to find somewhere in the evening that actually served Spanish food while he thumbed through a paperback.

Peregrine continued.

‘The reason I ask is that you might have to… how shall I put it…? emphasise… no, encourage, the Scottish part of you, should you decide to go into this business.’

‘Why is that?’ Claypole leaned back.

‘The Scots – the real Scots, not people like me who were educated in England – are terrible whingers.’

Claypole’s brow twitched.

‘Well, it’s true. The silly buggers think they’re a persecuted minority.’ Peregrine wasn’t smiling. ‘It’s incredibly childish. But I suppose being Scottish is pretty ghastly, so the only thing they’ve got is being more Scottish than someone else…’

The ghost of a smile crept into Claypole’s expression.

‘I’m serious! These people hate outsiders, especially the English, coming in and doing something clever which they should have done themselves if they didn’t have their heads up their bottoms. Hence all this independence kerfuffle. Load of old tommy-rot.’

The two men nodded gravely – Peregrine to emphasise his point; Claypole trying to keep a straight face.

‘It’s politics, really,’ Peregrine added, ‘this last bit of the process. We’ve got all the paperwork, and nothing very much should stand in its way. We just need to gee everyone up a bit and get the all-clear from the busybodies on the council. I’m not awfully good at schmoozing – tend to get people’s backs up.’

Silence again. Claypole struggled to think of what else he could ask.

‘Is it an island? Garvach, I mean.’

‘No,’ said Peregrine. ‘But it may as well be. You can only get to it by one road, and that goes over a tiny bridge over an isthmus that links it to the mainland. The isthmus is covered every few high tides, but mostly it just sits there being muddy and technically links us to the mainland. There’s an old tale about the place, actually.’

Claypole stifled a yawn. Peregrine carried on.

‘Saint Mungo, who wanted to marry the Chief of Garvach’s daughter, went to the old Chief and asked for his permission. The Chief said Mungo could marry the daughter if he could get a boat to circle the Chief’s lands in one day. The Chief knew it wasn’t possible, but Mungo accepted the challenge. Mungo set sail, and got around the peninsula of Garvach in twenty hours. He then dragged his boat across the muddy isthmus and met the Chief at the other side. The Chief said he would still not agree to the marriage of his daughter.’

Peregrine sat back. Claypole was still waiting for him to finish the story, but Peregrine just smiled.

‘Is that it?’ said Claypole in disgust.

‘Yes,’ said Peregrine. ‘You don’t like it?’

‘Well, it doesn’t have an ending. You know, I mean… did Saint Mungo just go home and have a cup of tea?’

‘Oh. Dunno. Probably killed everyone and took the land, I should think. That’s the sort of thing those chaps did.’

Claypole wrinkled his forehead. Celtic stories always seemed to be rather peculiar, obeying none of the usual rules that stories tend to. He had studied the genre while at university. (Or rather, he had read half a book about it in the pub.) There certainly was little justice, and rarely a moral. Stuff just happened to the hero, and then he died. This heavy hand of Fate was, although in Claypole’s view perfectly realistic, somewhat depressing. Claypole was not a sentimental man, but he liked a happy ending.

‘What did Mungo get sanctified for?’ asked Claypole. ‘Services to disappointing narrative?’

Peregrine smiled neutrally. As he did so, Claypole could see light-blue-blazer man finally fall forwards into his prawn-and-avocado mousse and instantly wake with a start, his face a shambles of green and pink.

‘Well,’ said Claypole, stretching extravagantly and making the leather on the ancient sofa squeak. ‘I don’t think this is something for me.’

Peregrine nodded slowly. ‘May I ask why?’ he said coolly.

The light-blue blazer had wiped his face with a crisp linen napkin, and was gleefully eating what he had so nearly breathed in. Claypole took a moment, dropping his shoulders. He would have loved to reply honestly. ‘Here are the reasons why I will not invest in your wind farm,’ he would like to have said. ‘One, there are no experts involved. Any business has to have experts. Two, if there were anything of any value there, the previous company – if they were professionals – would have sold it before they went bust. And, if they weren’t professionals, the work they have done so far probably isn’t worth anything. Three, it’s not based on sound principles. Basing any business on the whims of politicians is too risky. Those bastards change their minds every three minutes. Wind energy might be in vogue today, but who’s to say it won’t be nuclear tomorrow, or wave power, or something else? Four, you don’t believe in it. If you think that global warming is nonsense – which is the whole reason for the business to exist – why should anyone else? Five – and this is the most important – it doesn’t have the feel of a business that should work. That’s because for you it’s not a business – it’s a scam.’

But Claypole said none of this. Instead, he shrugged, and tried to look gently grave, as if telling a nine-year-old that their hamster has died in the night.

‘Just don’t fancy it,’ he said. ‘Best of luck with it, though. Brr.’

Claypole’s flat was in a mansion block in an area sandwiched between a trendy and a stuffy part of west London. He had bought at the very top of the market, and the service charge was high, but Claypole had always considered it worth it, if only because he was greeted by a porter when he got home. Claypole wasn’t entirely sure how to pronounce Wolé’s name, having only ever seen it written down, and he calculated that it would be ruder to get it wrong than not to say it at all. Wolé was too shy to use anyone’s name. So Claypole and Wolé nodded silently to each other this evening, as they did every evening, and performed knowing and manly winks.

The front door to his flat stuck against the letters and junk mail, and Claypole had to push his bulk against the door to force it open. He shuffled the assorted items into a deck, picked them up and puffed sweatily to the sitting room. Claypole had not decorated the place since buying it two years before, and had not even rearranged the furniture, also purchased from the previous occupant. She had been a woman of rather singular tastes. The purple and orange silks, the sheer curtains and lightshades, the ubiquitous African and Middle Eastern ‘style’ dark wood, and the overstuffed sofas with a thousand luxurious cushions gave it the air of a well-appointed Tangiers brothel. Claypole could not have cared less. No one ever came here, he had spent little waking time in it, and he neither cleaned nor tidied the place. Half his possessions were still in wilting cardboard boxes in the two unused spare bedrooms.

He hovered over the dusty dining table, leafing through this day’s paper doorstop. A freebie computer gaming magazine and Didge, a glossy rag for the technologically advanced media professional, were the periodicals. There was a bank statement, which he did not open, and a few bills of no apparent interest.

‘Brr,’ said Claypole, sweeping everything into the bin, save for one businesslike white envelope.

He examined his mobile phone idly for ten seconds or so and then put it back in his pocket. It was a conditioned reflex. He didn’t really want to find out who wanted his attention. He just looked at it automatically, like someone who is not hungry looking in a fridge. Getting up with purpose, he took an unopened bottle of single malt whisky from his briefcase, saw that it was older than he was and sneered with pleasure. He also took a crystal tumbler from a shelf and a tray of ice from the freezer. He lined all these items up. He poured three-quarters of a tumbler of whisky into the glass and added six cubes of ice. Before putting his lips to the brimming glass, he squinted at the bottle and then at the remaining ice cubes. He calculated that he should put no more than four ice cubes in each glass, or he would run out of ice before he had finished the bottle. Satisfied, he sat back in his chair and drank deeply.

‘Nyah!’ he pronounced with exquisite pain, and bared his teeth.

Taking out his phone again, it took him four scrolls and two clicks to order his usual: one family-sized Krakatoa Special pizza with three kinds of sausage, extra chilli oil, extra chillies and extra cheese; two large tubs of Fatty Arbuckle’s Famous Choctasmic ice cream; and four cans of different ballistically caffeinated and highly sugary drinks.

He leaned back in the chair with satisfaction, and looked sideways at the one remaining item of post. The white envelope. He took another massive draught of Scotch and crunched the ice. Then he poured himself another and drank it down. In the two minutes between drinking half a pint of whisky quickly and being drunk, his stomach burned unpleasantly and a high-pitched whine sounded in his ear. Claypole waited unblinkingly for these symptoms to be replaced with a warm body-wide buzz.

He picked up the letter, held it for a few seconds to his face as if about to sniff it and then opened it with undextrous violence. There were two pieces of paper. The larger one, with an embossed letterhead, he scanned and discarded. The smaller piece of paper was a cheque. Claypole regarded it without changing his expression. He put it on the table, facing him. Sipping Scotch all the while, he stared at it with unfocused grimness. He put his feet up on the table and picked the cheque up again. He put it down. He read it once more.

‘Pay… Gordon Claypole… Sixty-six thousand one hundred and eighty pounds only.’

Claypole took another belt of Scotch, sat upright and refilled the glass again, adding four more cubes of ice. He looked once more at the cheque.

Slowly, Claypole started to cry. For a while, no part of him moved. Tears formed and ran down his cheeks, but there were no other symptoms. Then his shoulders started to shift rhythmically and the sobbing began, remaining constant – neither growing in volume nor intensity. But it did continue, whisky the only punctuation, for the next half-hour.

When the doorbell went, Claypole dried his eyes and stumbled to the door in the full expectation that this would be the carbohydrate and fat delivery into which he could dive headlong with heavy-hearted abandon.

With Death comes honesty.

The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie

Pink’s, like many of the white-stuccoed buildings of St James’s, is a private members’ club. Some regard these clubs as not so much ‘private’ as ‘secret’, and certainly there are only two facts about Pink’s which appear in the public domain. The first is that the club has recently inherited the bulk of the estate of the artist James Hoogstratten, R.A. This ran into millions, and the club’s members have voted not to take the £30,000 each that they were due by the club’s constitution. Instead, they ploughed the entire windfall into boosting the quality and size of Pink’s wine cellar, and in acquiring van Gogh’s The Beech Tree, which now hangs modestly at the bottom of the main staircase. The second fact that is known about Pink’s is its strict dress code.

Wearing a suit and tie, in most lines of work these days, is a clear sign of a lack of seniority. But few men make the mistake of turning up at Pink’s without the requisite garb. If they did they would be subjected to the special torture of being forced to wear something the club provided. This would be a jacket that bordered on fancy dress, and a tie of such luridness and unfashionability that it could only be worn by a fringe comedian, or a castaway looking to be seen from 35,000 feet.

There are many rules in Pink’s. Many similar clubs have banned the use of mobile telephones, but Pink’s also bans trousers without a crease, soft shoes, collarless shirts, children, personal computers, and the wearing of hats and swords beyond the cloakroom. Pink’s considers itself rather avant-garde for having lifted – over ten years ago – its 240-year ban on women becoming members. But judging by the members present on the average hazy August afternoon, this happy news seems not yet to have been passed on to any actual women.

Peregrine MacGilp of MacGilp, one such member on one such afternoon, was perpetually irritated to have to smoke his cigarettes while standing in the street. But he used his time in the smoggy sunshine productively by simultaneously puffing and conducting an exchange of text messages with his niece. They had business to discuss.

‘Lawyer phoned,’ said the first incoming text. ‘We only have a week. GC is realistically our last chance.’

Peregrine replied, thumbing the buttons on his phone with hesitancy, hindered by long-sightedness and lack of expertise. ‘WILCO. REMINT ME WHAT WE NKOW OF GC?’

A minute later, his phone buzzed with another message. ‘Rumour is he sold biz for big ££. Some sort of tech/media thing.’

Peregrine decided to tease his niece. ‘GOLD-LOOKING, IS HE? ALL YOUR FRIENDS ARE. TALL TOO, I SUPPORT.’

‘Haven’t seen him since we were kids,’ replied the niece, ignoring the predictive text problems. ‘Might be Scottish?’

Peregrine texted back. ‘SOUND LIKE A MATTER OF THE UNIVERSE TYPE. BUSINESSMEN LIKE STRAIGHT TANKING. SHALL JUST BE MYSELF.’

It was just twenty seconds before the final communication.

‘Strongly advise you not to.’

Smiling, but with a wrinkled brow, Peregrine tucked his phone away in a well-tailored pocket. He did not generally meet high-powered entrepreneurs, and was unaccustomed to business meetings in which he was not the one being sold to. He inhaled deeply on the remainder of his cigarette. But Peregrine would deal with this challenge as he did all others in life, by assuming that things would probably work out for the best. They always did. So he went back inside his club, there to order a pot of Russian Caravan, and put to the back of his mind the feeling that he would rather his niece were joining him for this meeting on which his fate, and the fate of many others, would be determined.

As Peregrine waited patiently for his tea, the man he was due to meet was standing just a hundred yards away on Piccadilly, sweating at his reflection in the broad window of an expensive shop.

Gordon Claypole was tubby, and only in the thorax. His short legs and arms, over which he had only limited control, were thin and weak. He was not ‘a large man’. He was a fat man. This saddened him not just because of its genetic inevitability and the echo of his long-dead father, but because, having been a fat child, he had briefly been a normal-shaped young adult. At thirty-five, he was once again an egg with tentacles, and wished that he had never known what it was like to look anything other than odd. There was always something in his reflection to admonish, and inflict the persistent pain that, he supposed, dogs all people who are physically inadequate. He stared more closely at his reflection. Sometimes it was the beetroot bags under his eyes that struck him as ugly, sometimes the reddening bulb of a nose, or the collection of grey-green chins that hung from his jaw like stuffed shopping bags. Today, though, it was his oyster eyes and their network of scarlet veins that disgusted him. He also found time to loathe the dyed black hair that was losing the battle for influence over his huge potato of a head. And in these clothes – black suit, white shirt, black tie – he thought the entire ensemble gave him the appearance of a ghoulish and hard-living undertaker.

‘Fuck it,’ he burbled idly to his reflection as he stumbled on from the shop front and felt an ache in his chest.

Claypole was familiar with the other kind of private members’ club. The sort that spring up like dandelions, and very often disappear again as quickly, from the streets of Soho. A short stroll from St James’s, but a world away, the most octane-fuelled of the capital’s media workers and their hangers-on collide in these other haunts on weeknights, bitching, bragging, gossiping and flirting, getting quickly drunk and lording it shrilly over the waiting staff. The older ones are tired and lonely, with the resources to destroy careers, egos or emotions as they choose. The younger ones fight among themselves for position, or fame, or money, and possess the joint characteristics of overconfidence and desperation, a combination only otherwise found in lesser-league football. Only the lucky few, for all the talk, find a decent price for their souls.

So, like Lewis Carroll’s Alice trying to adjust to a new world, Claypole rubbed his eyes as he stepped through the small eighteenth-century door to Pink’s. The size of the entrance belied the club’s vast interior. It was stunning, too, in a faded sort of way. Like an ancient screen actress, it had former glory as an all-pervading memory, and it could not but impress even if it gave the impression that it no longer cared to do so. Shifting silently about, the members were, like the cool dark interior, old and rich. These men, in their fine suits, had never doubted their position and never wanted for anything. If these souls were for sale at all, they would be very expensive.

Claret-coloured and puffing from the walk, Claypole announced his presence to the moustachioed and liveried man at the front desk. Clearly ex-military, the man gave Claypole the same look of disdain bordering on disgust he gave all non-members. This was the look that allowed the club to charge its members a thousand pounds a year in membership fees. They didn’t want ever to receive that look again. They wanted the other look the ex-military man gave, to members only: a slight but intensely respectful nod.

Moving slowly behind the ex-military gent into the main library, Claypole stiffened. He was trying to give himself the same air of unfettered, world-owning confidence he could feel coming from the members as they flicked through the pages of the Daily Telegraph, or coughed discreetly into a Scotch and soda. But he did not feel at home. A thousand pounds was what it cost you to belong, although it was a fee you got to pay only if you already belonged.

Using the arm of the old leather sofa for leverage, Peregrine MacGilp rose to an imposing six foot two. His silver hair, just a little long and fuzzy at the back but with a thick and immaculate quiff at the front, topped a remarkably unlined and square-set face. He looked like a Serbian war criminal in a burgundy corduroy suit and navy-blue sweater, but with boyishly excited eyes. Peregrine was the sort of old man – seventy, maybe, but with the gait of a fifty-year-old – that could grace a luxury yacht brochure until he was ninety. Claypole would become the other kind of old man – a structureless, cushiony wheezer with a baked-bean head. Claypole, should he still be alive at seventy, might look at home in the ticket booth of a funfair.

‘My dear fellow,’ said Peregrine in an immense baritone, stretching out a muscular arm and bristling with welcome.

‘Hi,’ said Claypole, and shook the old man’s hand, but held his gaze for only the briefest of moments.

‘Gordon, isn’t it?’ asked Peregrine.

‘Just Claypole,’ muttered Claypole, and gave him a challenging look. Peregrine smiled.

‘Gosh. You mean you don’t use your first name?’

‘People just call me Claypole.’

‘Oh… how marvellous!’ Peregrine clapped his hands with delight. ‘Like that left-wing chap with the dark glasses. What’s his name? Bonzo.’

‘Bono. Yeah,’ said Claypole, narrowing his eyes.

‘That’s the fellow,’ said Peregrine gaily, clicking his fingers. ‘Or Plato, I suppose. He’s only got one name, hasn’t he? Or Liberace.’ He smiled at Claypole with icy grey eyes, and added with unselfconscious non sequitur, ‘What fun.’

‘Brr.’ Claypole cleared his throat, as he did habitually in company, like a man who has swallowed a sizeable fly but doesn’t want anyone to know about it.

‘Do have a pew,’ said Peregrine, looking pleased and preparing to sit down. ‘Do you fancy some tea?’

They both looked at a prissy brilliantined midget in a white mess jacket, who had appeared at Claypole’s elbow.

‘No, thanks,’ said Claypole.

‘Really? Or some sandwiches? Or something else? They have pretty much anything here… It was at that table over there that my grandfather once ate a record number of oysters, but, ah… A snorter, perhaps? Bit early to start opening the pipes, but be my guest if you…’

Claypole watched a nearby codger in a light-blue blazer being served something lurid involving prawns, avocado and aspic.

‘Nah. Brr. Let’s get on with it,’ said Claypole, and barrelled himself into a red leather sofa opposite Peregrine. His intention – to make a proprietory gesture – was undermined somewhat by the fact that he bounced perilously on the unexpectedly well-sprung seat. Peregrine sat slowly, still smiling magnificently. They exchanged small talk as Claypole rehearsed to himself the chain of events that had led him to this place at this time.

Claypole had thirty-four Facebook friends. So when Peregrine’s niece, Coky Viveksananda, who had 196 Facebook friends, requested to become number 35 some months previously, he was in no position to turn her down. She assured him in her message that their parents had known each other many years ago, and that they had met as children. He accepted her request and replied that indeed he remembered her, which he did not, and then examined her Facebook profile. There was a picture of a petite girl in shades, possibly of southern Asian origin, sitting on a lawn somewhere and smiling shyly. Her friends had names like Max von Strum and Felicia Hungerford and appeared to Claypole to be either smug or vacuous. But she listed her hobbies as ‘necromancy and darts’, and her job as ‘Brigadier-General of Starfleet Command’, and gave no other personal details, showing an amused disdain for the social networking medium that Claypole admired but could not bring himself to exhibit. No other communication had occurred between them until three days previously. Coky wondered – in a pleasantly un-pushy message – if he would be interested in meeting her uncle in regard to a business opportunity. So here he was, sitting opposite the laird of a desolate estate on the west coast of Scotland consisting of a bleak and bulky Gothic revival house, a few chilly cottages and a considerable chunk of… apparently nothing very much, according to its squire.

‘Bugger all. It’s useless,’ said Peregrine, with simple sincerity. ‘The Loch Garvach estate is some of the worst land in Europe. Three thousand acres of good-for-nothing floating bog.’

Claypole was surprised. He thought everywhere was used for something.

‘Oh yes, indeed,’ added Peregrine, driving home the point. ‘You can’t even walk on most of it.’

‘Brr.’ This was Claypole giving his usual cough, but this time it was nearly a laugh. Peregrine himself laughed unashamedly. It was loud, deep and used his full throat, even a bit of tongue.

‘So what have you been up to, then? What keeps Gordon – sorry, Claypole – out of the alehouses?’

Claypole seemed to study his hands for a moment before speaking.

‘I’ve been in the pre-school entertainment biz. Brr. Multimedia…’ Claypole drummed the fingers of one hand on the other. ‘I realised that phone Apps was the way to go. It’s happened in everything. And I had this bunch of content – movies and text – which I converted to a kick-ass App. Content’s about communities and fans these days, not…’

Peregrine was looking at him with bewilderment. ‘By “movies”, do you mean films?’

‘Er… yeah.’

‘American films?’

‘No, just films. Cartoons,’ said Claypole, blushing. ‘Cathy the Cow, then Colin the Calf.’

Peregrine squinted. ‘And by “text”, you mean books?’

‘Yeah.’

‘For children?’

‘Pre-school. Yeah.’

‘Babies, in fact?’

‘Er… yeah.’

‘Right-oh…’ Peregrine’s incomprehension was not reduced. ‘I have a mobile telephone, of course. But – and call me a Luddite if you must – I want it to… well, be a phone. Not another blasted computer!’ Peregrine chuckled.

Claypole beheld the older man, eyeing him intensely. Here was the grinning MacGilp of MacGilp (for what possible reason could a man need the same name twice?), completely contented, and utterly comfortable. Clearly he had been given the best that being British can offer. White, male and probably Protestant, yes. But also extremely privileged, classically educated, landed and moneyed, with the teeth of an Arab stallion. He seemed to be oblivious to modernity and more or less indifferent to the opinion of others. You couldn’t learn to be like that, thought Claypole. You had to be born in the right place at the right time, and to the right people.

‘Anyway,’ Claypole concluded. ‘Brr. I sold the company a month ago.’

‘So you’re free?’ asked Peregrine.

Claypole sat back in his chair, and did his best Cheshire Cat.

‘Well done,’ said Peregrine, in a matter-of-fact way. ‘I had a job in the City once, but I didn’t understand it. Ballsed it up. If I hadn’t inherited a fair chunk of lolly, God knows where I’d be.’

‘Thanks,’ muttered Claypole, chewing his jaw.

‘Shall I talk a little about my proposition?’ asked Peregrine freshly.

‘Sure,’ said Claypole. ‘It’s… er, making electricity from wind, right?’ He watched the midget in the mess jacket glide past and regretted that he had not ordered a plate of cakes, or a pie. Peregrine leaned forward and explained the history of wind farming at Loch Garvach.

Two years previously, a company called Aeolectricity had paid Peregrine a small amount of money in the expectation that when the wind farm received approval from the planning authorities and was subsequently built and generating electricity, they would pay him a handsome annual rent. The gamble for Aeolectricity was that if planning permission were not granted, they would lose their investment. On the other hand, if successful, it would make them many millions over the twenty-five-year life of the wind farm. But Aeolectricity had gone bust even though almost all the work had been done, and the whole project now belonged to Peregrine. This had all happened in the last couple of months, and the planning committee of the local council was now due to make its decision on whether the wind farm could go ahead or not.

‘It’s madness,’ began Peregrine in conclusion. ‘Why they leave it to the little people to make these decisions, I really don’t know. This and that sub-committee of Mr and Mrs McIdiot. They haven’t got a clue about how to plan a power station. Why would they? They’re not experts in anything very much, and they’re certainly not experts in this.’

Peregrine finished his monologue and his grey eyes flashed at Claypole. ‘Still. Pretty golden, eh?’

‘Right, yeah,’ said Claypole, looking across at the man in the light-blue blazer, who appeared to be falling asleep in front of his avocado mess. ‘So you need money?’

‘We need, more than anything else, a backer.’ Peregrine smiled. ‘A serious person. An homme d’affaires, if you like. Unpaid for the moment, but heavily rewarded if we’re successful.’

This evasion, Claypole knew instantly, spelled danger. Everyone needed money.

‘How much do you need?’ asked Claypole, in as bald a manner as he could manage.

‘As I say, it’s not so much the money…’

‘Yeah,’ said Claypole, closing his eyes with irritation in the manner he had seen done by business hotshots on television when faced with yet another common-or-garden mendacious incompetent. ‘How much do you need?’

‘I really don’t want your money, old chap,’ said Peregrine, not letting up with his smile. ‘I just need you to stand up in front of the powers that be and give them a bit of the old razzle-dazzle.’

‘Brr,’ said Claypole. ‘You really think the plan stacks up? Profit-wise?’

‘Oh yes. It’s a gold mine. Thanks to the government.’

‘There are government grants?’

‘Not quite. It’s cleverer than a straight hand-out.’ Peregrine leaned forward conspiratorially. ‘Because of these global warming do-dahs – you know, Britain has to reduce our carbon whatsits by such-and-such – anyone who has a wind farm can charge more for their electricity than someone with a coal-fired power station, or gas or whatever. A lot more. And there’s a lot of other financial how’s-your-fathers that make it even more attractive.’

Claypole scratched his nose.

‘Speaking personally,’ Peregrine continued, ‘I’m not absolutely convinced that there is such a thing as global warming… Doesn’t matter what I think, of course. Everyone else seems to think it’s important, and so do the powers that be. It’s the law.’ Peregrine looked around him for spies. ‘Don’t tell my niece that I don’t really believe in global warming, will you? She’s a fervent believer.’

‘Brr,’ said Claypole, attempting inscrutability. ‘But Loch Garvach is windy, yeah?’

‘Oh yes. Frightfully windy,’ said Peregrine.

‘Blow your hat off?’ suggested Claypole.

‘Blow your face off,’ corrected Peregrine. ‘Honestly, it would carry you off to Ireland.’ Then Peregrine was suddenly grave. ‘If the wind were an easterly… which it rarely is.’

‘Right,’ said Claypole, also suddenly serious.

They fell silent for a moment. The old man in the light-blue blazer was slipping further towards his plate of avocado and prawn, and Claypole wondered whether he should alert someone.

‘Do you go back to Scotland much?’ asked Peregrine.

‘Nah. Haven’t been there for years. Used to go on holiday there till Granny died. I stay put in London mostly. Spain for holidays.’

Peregrine sniffed the air. ‘Ah yes. Italia para nacer, Francia para vivir, España para morir. And of course you can’t beat the dear old Prado.’

The two men stared into the middle distance, remembering their respective Spanish holidays. Of the two of them, only Claypole could see how different those memories would be. Peregrine, a floozy named Minty or Bella in tow, probably drank delicious rosé with cravat-wearing Spanish nobility in the olive groves of delightfully dilapidated castles. To date, Claypole’s solo holidays had consisted of sleeping in the burning sun on plastic deckchairs next to tattooed plumbers from Brentwood with brattish children, and then trying to find somewhere in the evening that actually served Spanish food while he thumbed through a paperback.

Peregrine continued.

‘The reason I ask is that you might have to… how shall I put it…? emphasise… no, encourage, the Scottish part of you, should you decide to go into this business.’

‘Why is that?’ Claypole leaned back.

‘The Scots – the real Scots, not people like me who were educated in England – are terrible whingers.’

Claypole’s brow twitched.

‘Well, it’s true. The silly buggers think they’re a persecuted minority.’ Peregrine wasn’t smiling. ‘It’s incredibly childish. But I suppose being Scottish is pretty ghastly, so the only thing they’ve got is being more Scottish than someone else…’

The ghost of a smile crept into Claypole’s expression.

‘I’m serious! These people hate outsiders, especially the English, coming in and doing something clever which they should have done themselves if they didn’t have their heads up their bottoms. Hence all this independence kerfuffle. Load of old tommy-rot.’

The two men nodded gravely – Peregrine to emphasise his point; Claypole trying to keep a straight face.

‘It’s politics, really,’ Peregrine added, ‘this last bit of the process. We’ve got all the paperwork, and nothing very much should stand in its way. We just need to gee everyone up a bit and get the all-clear from the busybodies on the council. I’m not awfully good at schmoozing – tend to get people’s backs up.’

Silence again. Claypole struggled to think of what else he could ask.

‘Is it an island? Garvach, I mean.’

‘No,’ said Peregrine. ‘But it may as well be. You can only get to it by one road, and that goes over a tiny bridge over an isthmus that links it to the mainland. The isthmus is covered every few high tides, but mostly it just sits there being muddy and technically links us to the mainland. There’s an old tale about the place, actually.’

Claypole stifled a yawn. Peregrine carried on.

‘Saint Mungo, who wanted to marry the Chief of Garvach’s daughter, went to the old Chief and asked for his permission. The Chief said Mungo could marry the daughter if he could get a boat to circle the Chief’s lands in one day. The Chief knew it wasn’t possible, but Mungo accepted the challenge. Mungo set sail, and got around the peninsula of Garvach in twenty hours. He then dragged his boat across the muddy isthmus and met the Chief at the other side. The Chief said he would still not agree to the marriage of his daughter.’

Peregrine sat back. Claypole was still waiting for him to finish the story, but Peregrine just smiled.

‘Is that it?’ said Claypole in disgust.

‘Yes,’ said Peregrine. ‘You don’t like it?’

‘Well, it doesn’t have an ending. You know, I mean… did Saint Mungo just go home and have a cup of tea?’

‘Oh. Dunno. Probably killed everyone and took the land, I should think. That’s the sort of thing those chaps did.’

Claypole wrinkled his forehead. Celtic stories always seemed to be rather peculiar, obeying none of the usual rules that stories tend to. He had studied the genre while at university. (Or rather, he had read half a book about it in the pub.) There certainly was little justice, and rarely a moral. Stuff just happened to the hero, and then he died. This heavy hand of Fate was, although in Claypole’s view perfectly realistic, somewhat depressing. Claypole was not a sentimental man, but he liked a happy ending.

‘What did Mungo get sanctified for?’ asked Claypole. ‘Services to disappointing narrative?’

Peregrine smiled neutrally. As he did so, Claypole could see light-blue-blazer man finally fall forwards into his prawn-and-avocado mousse and instantly wake with a start, his face a shambles of green and pink.

‘Well,’ said Claypole, stretching extravagantly and making the leather on the ancient sofa squeak. ‘I don’t think this is something for me.’

Peregrine nodded slowly. ‘May I ask why?’ he said coolly.

The light-blue blazer had wiped his face with a crisp linen napkin, and was gleefully eating what he had so nearly breathed in. Claypole took a moment, dropping his shoulders. He would have loved to reply honestly. ‘Here are the reasons why I will not invest in your wind farm,’ he would like to have said. ‘One, there are no experts involved. Any business has to have experts. Two, if there were anything of any value there, the previous company – if they were professionals – would have sold it before they went bust. And, if they weren’t professionals, the work they have done so far probably isn’t worth anything. Three, it’s not based on sound principles. Basing any business on the whims of politicians is too risky. Those bastards change their minds every three minutes. Wind energy might be in vogue today, but who’s to say it won’t be nuclear tomorrow, or wave power, or something else? Four, you don’t believe in it. If you think that global warming is nonsense – which is the whole reason for the business to exist – why should anyone else? Five – and this is the most important – it doesn’t have the feel of a business that should work. That’s because for you it’s not a business – it’s a scam.’

But Claypole said none of this. Instead, he shrugged, and tried to look gently grave, as if telling a nine-year-old that their hamster has died in the night.

‘Just don’t fancy it,’ he said. ‘Best of luck with it, though. Brr.’

Claypole’s flat was in a mansion block in an area sandwiched between a trendy and a stuffy part of west London. He had bought at the very top of the market, and the service charge was high, but Claypole had always considered it worth it, if only because he was greeted by a porter when he got home. Claypole wasn’t entirely sure how to pronounce Wolé’s name, having only ever seen it written down, and he calculated that it would be ruder to get it wrong than not to say it at all. Wolé was too shy to use anyone’s name. So Claypole and Wolé nodded silently to each other this evening, as they did every evening, and performed knowing and manly winks.

The front door to his flat stuck against the letters and junk mail, and Claypole had to push his bulk against the door to force it open. He shuffled the assorted items into a deck, picked them up and puffed sweatily to the sitting room. Claypole had not decorated the place since buying it two years before, and had not even rearranged the furniture, also purchased from the previous occupant. She had been a woman of rather singular tastes. The purple and orange silks, the sheer curtains and lightshades, the ubiquitous African and Middle Eastern ‘style’ dark wood, and the overstuffed sofas with a thousand luxurious cushions gave it the air of a well-appointed Tangiers brothel. Claypole could not have cared less. No one ever came here, he had spent little waking time in it, and he neither cleaned nor tidied the place. Half his possessions were still in wilting cardboard boxes in the two unused spare bedrooms.

He hovered over the dusty dining table, leafing through this day’s paper doorstop. A freebie computer gaming magazine and Didge, a glossy rag for the technologically advanced media professional, were the periodicals. There was a bank statement, which he did not open, and a few bills of no apparent interest.

‘Brr,’ said Claypole, sweeping everything into the bin, save for one businesslike white envelope.

He examined his mobile phone idly for ten seconds or so and then put it back in his pocket. It was a conditioned reflex. He didn’t really want to find out who wanted his attention. He just looked at it automatically, like someone who is not hungry looking in a fridge. Getting up with purpose, he took an unopened bottle of single malt whisky from his briefcase, saw that it was older than he was and sneered with pleasure. He also took a crystal tumbler from a shelf and a tray of ice from the freezer. He lined all these items up. He poured three-quarters of a tumbler of whisky into the glass and added six cubes of ice. Before putting his lips to the brimming glass, he squinted at the bottle and then at the remaining ice cubes. He calculated that he should put no more than four ice cubes in each glass, or he would run out of ice before he had finished the bottle. Satisfied, he sat back in his chair and drank deeply.

‘Nyah!’ he pronounced with exquisite pain, and bared his teeth.

Taking out his phone again, it took him four scrolls and two clicks to order his usual: one family-sized Krakatoa Special pizza with three kinds of sausage, extra chilli oil, extra chillies and extra cheese; two large tubs of Fatty Arbuckle’s Famous Choctasmic ice cream; and four cans of different ballistically caffeinated and highly sugary drinks.

He leaned back in the chair with satisfaction, and looked sideways at the one remaining item of post. The white envelope. He took another massive draught of Scotch and crunched the ice. Then he poured himself another and drank it down. In the two minutes between drinking half a pint of whisky quickly and being drunk, his stomach burned unpleasantly and a high-pitched whine sounded in his ear. Claypole waited unblinkingly for these symptoms to be replaced with a warm body-wide buzz.

He picked up the letter, held it for a few seconds to his face as if about to sniff it and then opened it with undextrous violence. There were two pieces of paper. The larger one, with an embossed letterhead, he scanned and discarded. The smaller piece of paper was a cheque. Claypole regarded it without changing his expression. He put it on the table, facing him. Sipping Scotch all the while, he stared at it with unfocused grimness. He put his feet up on the table and picked the cheque up again. He put it down. He read it once more.

‘Pay… Gordon Claypole… Sixty-six thousand one hundred and eighty pounds only.’

Claypole took another belt of Scotch, sat upright and refilled the glass again, adding four more cubes of ice. He looked once more at the cheque.

Slowly, Claypole started to cry. For a while, no part of him moved. Tears formed and ran down his cheeks, but there were no other symptoms. Then his shoulders started to shift rhythmically and the sobbing began, remaining constant – neither growing in volume nor intensity. But it did continue, whisky the only punctuation, for the next half-hour.

When the doorbell went, Claypole dried his eyes and stumbled to the door in the full expectation that this would be the carbohydrate and fat delivery into which he could dive headlong with heavy-hearted abandon.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books/Marble Arch Press (August 4, 2015)

- Length: 288 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476730486

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“If P.G. Wodehouse had created Ignatius J. Reilly, the result would be Whirligig…Brilliantly written, the kind of novel not to be read too quickly lest the reader miss one perfectly placed word.”

– Kirkus (Starred Review)

“This is a book I wish I’d written and a story I loved to read.”

– Hardeep Singh Kohli, Indian Takeaway: A Very British Story

“Strong and clear and fresh and rousing.”

– Jez Butterworth, Author of Jerusalem

“Told with real clarity, it is not hard to imagine this story transferring easily to television.”

– The Spectator

“Macintyre has created a hilarious parody of the City man, in all his impractical glory."

– The Times

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Whirligig Trade Paperback 9781476730486