Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

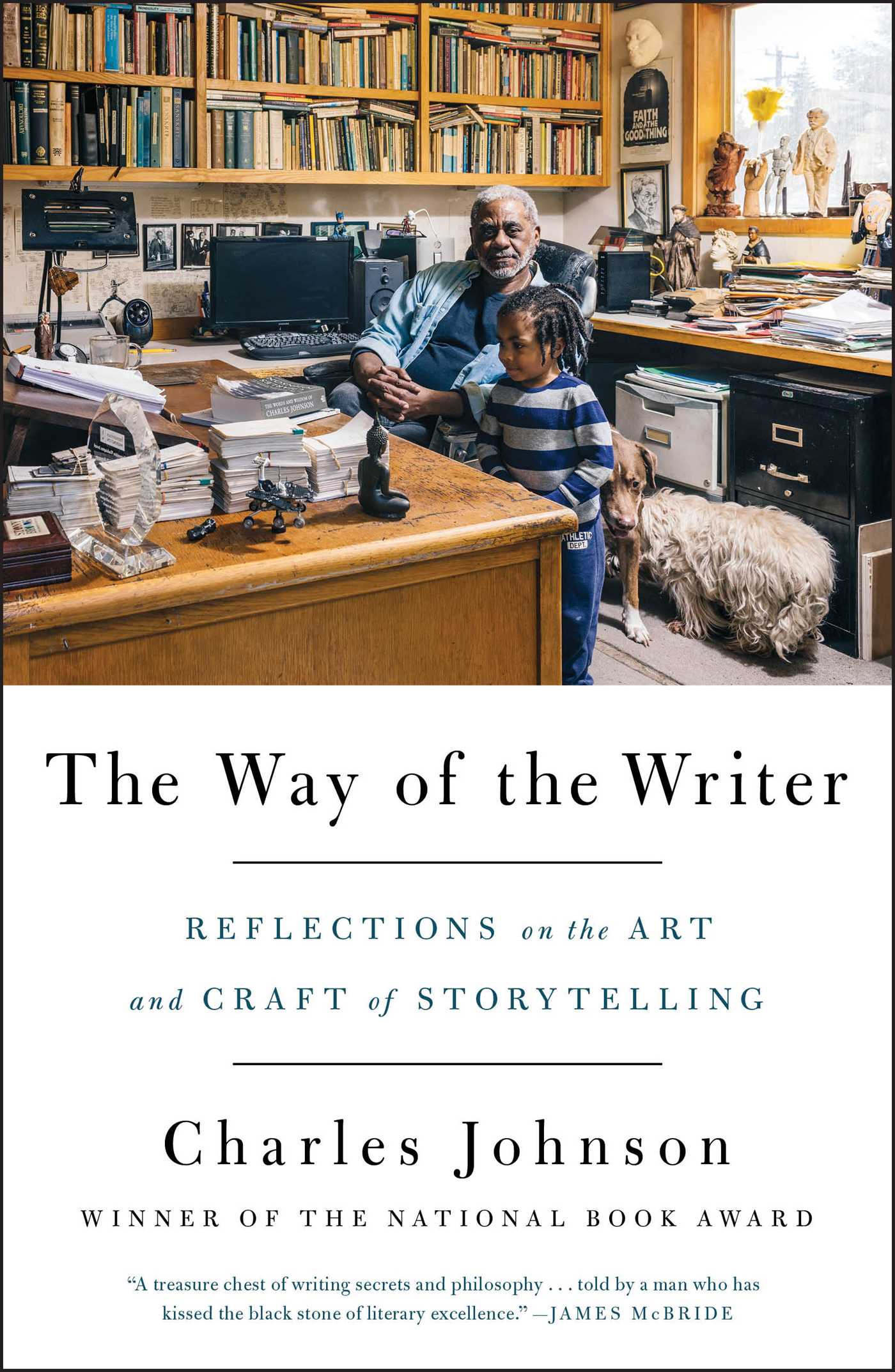

An award-winning novelist, philosopher, essayist, screenwriter, professor, and cartoonist, Charles Johnson has devoted his life to creative pursuit. His 1990 National Book Award-winning novel Middle Passage is a modern classic, revered as much for its daring plot as its philosophical underpinnings. For thirty-three years, Johnson taught and mentored students in the art and craft of creative writing. The Way of the Writer is his record of those years, and the coda to a kaleidoscopic, boundary-shattering career.

Organized into six accessible, easy-to-navigate sections, The Way of the Writer is both a literary reflection on the creative impulse and a utilitarian guide to the writing process. Johnson shares his lessons and exercises from the classroom, starting with word choice, sentence structure, and narrative voice, and delving into the mechanics of scene, dialogue, plot and storytelling before exploring the larger questions at stake for the serious writer. What separates literature from industrial fiction? What lies at the heart of the creative impulse? How does one navigate the literary world? And how are philosophy and fiction concomitant?

Luminous, inspiring, and imminently accessible, The Way of the Writer is a revelatory glimpse into the mind of the writer and an essential guide for anyone with a story to tell.

Excerpt

People sometimes wonder what a person was like before he or she became a writer. What was that person’s childhood like? In my case, I imagine that my being an only child growing up in the 1950s in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, Illinois, in the shadow of Northwestern University, shaped my life in more ways than I can imagine.

I was born on April 23 (Shakespeare’s birthday), 1948, at a place I described in my novel Dreamer: Community Hospital, an all-black facility. In my novel I renamed this important institution “Neighborhood Hospital,” and called the woman who spearheaded its creation, Dr. Elizabeth Hill, by the fictionalized name Jennifer Hale. In the late 1940s, Dr. Hill—one of Evanston’s first black physicians—was barred by segregation from taking her patients to all-white Evanston Hospital. Instead, she was forced to take them to a hospital on the South Side of Chicago, and quite a few of her patients died in the ambulance on the way. Almost single-handedly (or so I was told as a child), Dr. Hill organized black Evanstonians (and some sympathetic whites) to create a black hospital. Our family patriarch, my great-uncle William Johnson, whose all-black construction crew (the Johnson Construction Co., which this book honors on its title page) built churches, apartment buildings, and residences all over the North Shore area, would go nowhere else for treatment, even after Evanston Hospital was integrated in the 1950s. And every black baby born to my generation in Evanston came into the world there—my classmates and I all had in common the fact that we had been delivered by Elizabeth Hill. She considered us her “children.” Even when I was in my early twenties she knew me by sight and would ask what I’d been up to since I last saw her.

Predictably, then, I grew up in a black community in the 1950s that had the feel of one big, extended family. Ebenezer A.M.E. Church, where I was baptized (and later my son) and married, was a central part of our collective lives. In an atmosphere such as this, everybody knew their neighbors and saw them in church on Sunday; it was natural for grown-ups to keep an eye on the welfare of their neighbors’ children and to help each other in innumerable ways. In short, Evanston in the 1950s was a place where, beyond all doubt, I knew I was loved and belonged.

My father worked up to three jobs to ensure our family never missed a meal. We weren’t poor, but neither were we wealthy or middle-class. Every so often my mother took a job to help make ends meet, including one at Gamma Phi Beta sorority at Northwestern University, where she worked as a cleaning woman during the Christmas holidays. She brought me along to help because she couldn’t afford a babysitter. I remember her telling me that the sorority’s chapter said no blacks or Jews would ever be admitted into its ivied halls. My mother brought home boxes of books thrown out by the sorority girls when classes ended, and in those boxes I found my first copies of Mary Shelley and Shakespeare. I read them, determined that the privileged girls of that sorority would never be able to say they knew something about the Bard that the son of their holiday cleaning woman didn’t. Decades later in 1990 Northwestern’s English department actively and generously pursued me for employment by offering me a chair in the humanities, which I declined.

Along with those books from Northwestern, my mother filled our home with books that reflected her eclectic tastes in yoga, dieting, Christian mysticism, Victorian poetry, interior decorating, costume design, and flower arrangement. On boiling hot Midwestern afternoons in late July when I was tired of drawing (my dream was to become a cartoonist and illustrator), I would pause before one of her many bookcases and pull down a volume on religion, the Studs Lonigan trilogy, poetry by Rilke, The Swiss Family Robinson, Richard Wright’s Black Boy, an 1897 edition of classic Christian paintings (all her books are now in my library), or Daniel Blum’s Pictorial History of the American Theatre 1900–1956, which fascinated me for hours. She was always in book clubs, and I joined one, too, to receive monthly new works of science fiction when I was in my middle teens. (Believe it or not, I had a hardcover first edition of Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, which I’ve always regretted letting slip away from me.)

As an only child, books became my replacement for siblings. Exposed to so many realms of the imagination, I vowed to read at least one book a week after I started at Evanston Township High School (from which, by the way, my mother had graduated in the late thirties). I started with adventure stories like those by Ian Fleming and ended my senior year with Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians. I spent hours each week at a newsstand selecting the next paperback I’d spend several days of my life with. And, as might be expected, it happened that one week I finished early—on a Tuesday, I recall—and I thought, “God, what do I do now with the rest of the week?” So I read a second book. Then it became easy to make it three books a week, and I did think—but only once—that someday it might be nice to have my name on the spine of a volume I’d written.

And so, again, ours was a house not just of provocative books but also inexpensive and intriguing (to me) art objects that Mother found at flea markets and rummage sales. When she couldn’t find them, she built them—for example, wall shelves with interesting designs to hold small figurines. We’d read the same books together sometimes, Mother and me, and discuss them. I think she relied on me for this, even raised me to do it, since my hardworking father had little time for books. She had the soul of an actress, a biting wit, and loved art. She’d always wanted to be a teacher, but couldn’t because she suffered from severe bouts of asthma. So she made me her student. Like so many other things I owe to my mother, I am indebted to her for seducing me with the beauty of blank pages—a diary she gave me to record my thoughts. But this was by no means a new infatuation. As with books, it was into drawing that I regularly retreated as a child. There was something magical to me about bringing forth images that hitherto existed only in my head where no one could see them. I remember spending whole afternoons blissfully seated before a three-legged blackboard my parents got me for Christmas, drawing and erasing until my knees and the kitchen floor beneath me were covered with layers of chalk and the piece in my hand was reduced to a wafer-thin sliver.

Something to understand about Evanston in the 1950s and ’60s is that, unlike many places, the public schools were integrated. From the time I started kindergarten I was thrown together with kids of all colors, and I found it natural to have friends both black and white. Evanston Township High School, we were constantly reminded, was, at the time, rated the best public high school in the nation. It was a big school, almost like a small college—my graduating class had almost a thousand students; black students made up 11 percent of that population. In its progressive curriculum we found an education provided, clearly, by the wealthy white Evanston parents who sent their children there. I took advantage of all the art and photography, literature and history classes.

And to its credit, ETHS offered a yearly creative-writing class taught by the short-story writer Marie-Claire Davis. At the time she was publishing in the Saturday Evening Post. As an aspiring cartoonist, I thought writing stories was fun and I came alive in my literature classes, where we read Orwell, Shakespeare, Melville, and Robert Penn Warren, but writing wasn’t the kick for me that drawing was. Regardless, I let a buddy talk me into enrolling in Marie’s class with him. We talked to each other the whole time and barely listened to poor Marie. But she put Joyce Cary’s lovely book Art and Reality in front of us, without discussing it in class, and with the hope that we might read it on our own, which I did, and something in me so enjoyed his essays on art and aesthetics that I thought, yes, someday I’d like to do a book like this, too. (You might say you’re holding that book in your hands right now.) When I turned in my three stories for Marie’s class in 1965, she rushed them into print in the literary section of our school’s newspaper (with my illustrations), which she supervised. I always feel indebted to her. And so in the 1990s I established an award, the Marie-Claire Davis Award, at the high school—$500 for the best senior student portfolio of creative writing. For years before her death, Marie would travel from Florida to shake the hand of the winner of that award.

Inevitably, the passion for drawing led me to consider a career as a professional artist. From the Evanston Public Library I lugged home every book on drawing, cartooning, and illustration, and collections of early comic art (Cruikshank, Thomas Rowlandson, Daumier, Thomas Nast), and pored over them, considering what a wonderful thing it would be—as an artist—to externalize everything I felt and thought in images. Some Saturday mornings I sat on the street downtown with my sketchbook, trying to capture the likenesses of buildings and pedestrians. And I made weekly trips to Good’s Art Supplies to buy illustration board with my allowance and money earned from my paper route (and later from a Christmas job working nights until dawn on the assembly line at a Rand McNally book factory in Skokie, and from still another tedious after-school job cleaning a silks-and-woolens store where well-heeled white women did their shopping). Good’s was a little store packed to the ceiling with the equipment—the tools—I longed to buy. The proprietor, a fat, friendly man, tolerated my endless and naïve questions about what it was like to be an artist and what materials were best for what projects; he showed me a book he’d self-published on his theory of perspective (I never bought it), and after he’d recommended to me the best paper for my pen-and-ink ambitions, I strapped my purchase onto the front of my bicycle and pedaled home.

For a Christmas present my folks finally did buy me one of Good’s drawing tables, new for $25. I made space for it in my bedroom and set it up like a shrine. That table would carry me through two years of drawing furiously for my high school newspaper (my senior year, in 1966, I received two second-place awards in the sports and humor divisions for a comic strip and panel from the Columbia Scholastic Press Association’s national contest for high school cartoonists), through my first professional job as an illustrator when I was seventeen—drawing for the catalog of a magic-trick company in Chicago. And then that first drawing table was with me, like an old friend, for the next four years of college when I drew thousands of panel cartoons, political cartoons, illustrations (even the design for a commemorative stamp), and every kind of visual assignment for my college newspaper, for the Chicago Tribune (where I interned in 1969, then worked for as a stringer when I returned to college), for a newspaper in southern Illinois, and for many magazines known as the “black press” in that era: Jet, Ebony, Black World (né Negro Digest), and Players (a black version of Playboy), all of which culminated in 1970 when I was twenty-two years old with an early PBS drawing show, Charlie’s Pad, that I created, hosted, and co-produced.

After that early, exhaustive seven-year career, I was ready to start writing fiction full-time. To tell stories with words and not just visual images.

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (December 6, 2016)

- Length: 256 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501147210

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Those of us who put pen to paper for a living have known of Charles Johnson for a very long time. He is one of America’s greatest literary treasures. He is a skilled wordsmith, superb craftsman, master of understatement, philosopher, cartoonist, and deeply talented novelist whose 1991 novel Middle Passage, (which won the National Book Award for fiction) predates the current surfeit of Underground Railroad novels by a good two decades. Like the great Ralph Ellison to whom he is often compared, he will forever cast a long shadow over us who follow in his wake. Here he graciously opens up the treasure chest of writing secrets and philosophy for those of us who seek to kneel at the tree of learning, told by a man who has kissed the black stone of literary excellence.”—James McBride, National Book Award-winning author of The Good Lord Bird and The Color of Water

"If you're looking to learn to tell stories in written form, look no further. This book is as accessible as it is profound, lively, practical, and full of earned wisdom. I was a student of Charles Johnson's, and can vouch for the power and value of his teaching. There are plenty of craft books available out there, but this is the only one I know of that is--and I don't think I'm exaggerating--indispensable."--David Guterson, author of Snow Falling on Cedars

"Charles Johnson has given us a book that will hopefully place a gentle but firm hand on the shoulder of every writer. Here are short essays offering advice, writing life insight and encouragement to anyone wishing to master the art of storytelling. Johnson's book is a reminder that good writing consists of more than sleeping with the dictionary. It requires a major commitment to the love of language."-- E. Ethelbert Miller, award-winning poet and 2016 recipient of the Association of Writers & Writing Programs George Garrett Award for Outstanding Community Service in Literature

"Charles Johnson here provides—as his subtitle promises—'reflections on the art and craft of storytelling.' It’s a welcome addition to the small shelf of useful books on the way of the writer and one that belongs with those of his mentor, John Gardner. Here the writer links the personal with the professional in ways that both inspire and instruct. Use this book (a) to deepen your familiarity with the work of a distinguished author, (b) to understand how serious practitioners address their art and (c) to improve your own."--Nicholas Delbanco, author of The Years

"This is a book for many readers. If you are an aspiring writer, the path that Dr. Johnson sets out is a clear guide to your destination—whether you become a best-selling novelist or a top non-fiction writer or not. You will find a compass in this book that will direct you towards a real way that will fulfill your efforts. There is much practical advice and worldview wisdom here that will sustain you in your journey. Those who are on a different path (as readers) will also find fulfillment here. Dr. Johnson sets out original and illuminating guides on how to confront literary fiction—especially philosophical fiction. These reflections advance critical theory toward literature that is, itself, philosophy. This is a must-buy for both of these travelers. The destination will more than reward the price of the ticket."--Michael Boylan, Professor of Philosophy, Marymount University and author of Naked Reverse: A Novel

"An honest, engaging, and wonderfully inspiring book for both writers and teachers. Charles Johnson’s deep intelligence, joyful rigor and refreshing iconoclasm are evident in every subject he covers here. Philosophical and practical, The Way of the Writer is sure to become a classic in the mold of John Gardner’s excellent books on writing."--Dana Spiotta, author of Innocents and Others

"A meditation on the meaning of literature and practical guide to the art and craft of writing fiction."--Library Journal

“Charles Johnson has a long-standing reputation as one of the world’s greatest fiction writers. Now in this brilliant new book, The Way of the Writer, he offers us an eclectic meditation on the storyteller’s craft that is by turns memoir, instructional guide, literary critique, and philosophical treatise. Every reader will be deeply enriched by the book.”—Jeffery Renard Allen, author of Song of the Shank and Rails Under My Back

“All writers will welcome the useful tips and exercises, but the book will also appeal to readers interested in literature and the creative process. Johnson’s wonderful prose will engage readers to think more deeply about how to tell a story and consider the truth-telling power of the arts.”--Library Journal STARRED review

“Throughout, Johnson’s voice is generous and warm, even while he is cautioning writers to be their own ruthless editors. A useful writing guide from an experienced practitioner.”—Kirkus Reviews

"National Book Award winner Johnson (Middle Passage, 1990) has taught creative writing for over 30 years and now shares his well-refined thoughts on how best to develop literary taste and technique.... Every aspect of this writing manual, which is laced with memoir, illustrates Johnson’s seriousness of purpose about literature and his laser focus on the thousands of small choices that shape a written work. The result is a book that will be appreciated by aspiring writers and everyone who shares Johnson’s delight in the power of words."--Booklist

"A meditation on the daily routines and mental habits of a writer...the book radiates warmth...a writer’s true education might start in institutions, it seems, but for Johnson it is more a lineage of good, memorable talk.”--New York Times

“Eloquent, inspiring and wise, The Way of the Writer is a testament to the methods and advice the author espouses, and even if you aren’t an aspiring novelist, Johnson’s book is a fascinating glimpse into the mind of one of our finest writers.”--Seattle Times

"Writers who haven’t had the opportunity to study with Dr. Charles Johnson during the past 40 years are now in luck. The novelist, essayist, cartoonist, and philosopher has collected the creative lessons he’s learned along the way in a new practical and semi-autobiographical guide."--Tricycle

"An instructive, inspiring guide to the craft and art of writing."--Chicago Review of Books

"One of America's finest novelists and foremost thinkers pondering the cosmos of literature...inspiring."--USA Today

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Way of the Writer Hardcover 9781501147210

- Author Photo (jpg): Charles Johnson Lynette Huffman-Johnson(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit