Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

From multi-award-winning author Yan Ge, a shimmering, genre-bending English-language debut that announces the next phase in a major literary career.

“As haunting, dreamlike, and addictive as a melatonin-induced slumber.” —Nylon

“Deft... Elsewhere [explores] the power of language across the Chinese diaspora to either bring people together or push them apart.”—The New York Times

In twenty years, Yan Ge has authored thirteen books written in Chinese, working across an impressive range of genres and subjects. Now, Yan Ge transposes her dynamic storytelling onto another linguistic landscape. The result is a collection humming with her trademark wit and style—and with the electricity of a seasoned artist flexing her virtuosity with a new medium.

A young woman bonds with an encampment of poets after a devastating earthquake. Against her better judgment, a college student begins to fall for an acquaintance who might be dead. And a Confucian disciple returns to the Master bearing a jar full of grisly remains. Weaving between reality and dreamy surreality, these nine stories wend toward elsewhere, a comforting, frustrating, just-out-of-reach place familiar to anyone who has ever experienced longing. Through it all Yan Ge’s protagonists peer thoughtfully at their own feelings of displacement—physical or emotional, the result of travel, emigration, or exile. Brilliant and irresistibly readable, Elsewhere explores the utility (or not) of art in the face of lonesomeness, quotidian, and spectacular.

This highly anticipated collection is further proof that Yan Ge is a generational literary talent, to be watched closely for decades to come.

Excerpt

Outside the Little House, Old Stone was talking about geese.

“Their intestines. That’s the best part,” he said. “The best goose intestines come from White Family Town; do you know why★”

“No idea,” I said.

“The women there have strong and slender fingers. The perfect kind of fingers for plunging into the goose’s asshole and yanking out the entrails while it’s still alive. They do it with precision and determination. They do this in a flash to preserve its tenderness.”

“I’m a vegetarian.”

He shook his head. “Why★”

I thought about how to reply.

“That’s no good,” he said. “Plus, I don’t think I’ve seen you eating since you came here.”

“I don’t feel hungry,” I said.

He turned around to the table next to us and shouted, “Small Bamboo! Can you talk some sense into this girl★”

Small Bamboo had fallen asleep in his chair. It was almost 3 a.m.

“Anyway,” he said, turning back to me, “guess which part of the cow the yellow throat comes from★”

“Its throat★”

“Ha!” He reached for his beer and took a long pull. “I’ve asked more than a hundred people this question. Nobody’s got it right. It comes from the cow’s coronary artery. And it has to be the right one. Because the right one’s thinner than the left one, so it gets cooked very quickly in the hot pot. Do you know how many seconds it takes to cook the yellow throat★”

“Uh-uh.”

“Eight seconds. Lots of people overcook it. That’s why you should never throw a piece of yellow throat into the pot. Hold it with chopsticks and dip it into the soup. Count to eight and take it out. Only this way will it be crispy and chewy.”

“I need to go to bed now,” I said.

“Sure. You go.” He took another mouthful from his beer bottle.

“Aren’t you going to sleep★”

“Ah no, no, I’m fine. When you are old you don’t need to sleep. I’ll just get another beer.”

He stood up and walked into the Little House. The light was still on. Sister Du was curled up on a booth seat, snoring. I watched through the window as Old Stone went behind the bar, grabbed a Tsingtao, and returned.

“I’ll ask her to put it on my tab in the morning.” He slumped back into his chair.

“I’m going now. Good night.” I stood up and walked back into the tent I shared with Vertical.

Small Bamboo had brought me to the Little House three days earlier. When he bumped into me, I was sitting on a bench outside my apartment compound, reading a book.

“Hey, Pigeon,” he said, coming swiftly across the street towards me. “What are you doing here★”

“Just reading,” I said, waving my book at him. “To kill some time.”

He tilted his head and read: “The Plague. I didn’t know you kids still read Camus.”

“Some of us do.”

“Where are you staying these days★” he asked.

“I’m camping in the courtyard, with my neighbors.” I pointed back over my head.

“That’s no fun,” Small Bamboo said. “Why don’t you come with me to the Little House★ We’re all staying there in the square: Old Stone, Young Li, Six Times, Vertical, Chilly, and lots of other poets.”

“But I don’t write poems,” I said.

He grinned. “It doesn’t matter. Just come with me.”

We walked to the Little House. The buses hadn’t been running since the twelfth and there were no taxis. Small Bamboo had smoked three cigarettes by the time he finally remembered to offer me one. I told him I didn’t smoke.

“You’re sensible. Cigarettes kill you.” He nodded, taking out another one and lighting it up.

We went across the Second Ring Road and turned into Ping’an Square.

“Wow,” I said.

The sunken square was brimming with tents, of various sizes and spectacular styles, their colors spanning the full visible spectrum. Small Bamboo pointed at the building at the far end of the square and told me the Little House was on that corner. We descended into the square and wove our way through it. The tents were clustered closely together and cast shadows over one another. People sat outside, eating, chatting, bartering. Vendors elbowed past with their baskets, selling food, magazines, T-shirts, and cosmetics. Kids chased one another, laughing. We steered through, Small Bamboo nodding at acquaintances and friends. Ahead of us, I saw a gigantic scarlet tent. It looked like a castle.

“That’s Young Li’s,” Small Bamboo said. “One big living room and three bedrooms for him, his wife, and two kids. There’s even a kitchen inside. God knows where that prawn got it from!”

It was a warm late May afternoon. The air was stale and humid. We walked from the sunken square up the steps and arrived at a run-down pub. Above, three big white characters hung, which read: The Little House. A dot in the first character was missing. A large group of men and women—the poets—sat outside, drinking beer. Small Bamboo introduced me: “This is Pigeon.”

“Pigeon!” they called out together, like a choir singing.

“I’ve heard about you,” one of them, a man in his forties, said. “You’re the kid who writes fiction.”

A middle-aged woman in a red floral dress looked me up and down. “You seem like a smart kid,” she said. “You should write poems.”

“Ignore these old drunks,” Small Bamboo said apologetically. “You go sit with Vertical.” He pointed me to a table on the side, at which a young woman and two men in their twenties sat. They waved at me gleefully.

Later I realized they were all in varying degrees of drunkenness. Some had been drinking since Monday; some had started on the evening of the twelfth. Sister Du, the owner of the Little House and Small Bamboo’s cousin, had driven her mini-truck to the wholesale market outside the city three times to restock beer. The supermarkets nearby had nothing left.

“And all of these rats here, they don’t even bother to pay,” Sister Du said. “★‘Put it on the tab’ they say—but nobody ever opened a tab!”

“I’ll have tea, please,” I said, taking out my wallet.

“Ah, come’n take a beer,” she said, and opened a Tsingtao for me. “I’ll put it on the tab.”

I took the bottle, walked outside, and sat down at the table with Vertical, her boyfriend Chilly, and Six Times. A woman with a basket approached, wondering if any of us would be interested in purchasing her goods. She lifted up the lid, revealing the little turtles inside. They were luminous, as white as pearls.

We were admiring the turtles when the alarm rang out in the sky.

“Always this time of day,” the woman said. She covered her basket and trotted away.

That night I washed my face for the first time since the twelfth and slept in Vertical’s tent. There was moaning coming, off and on, from different directions. Someone sang until the small hours. Eventually, I slept like a dead person and did not dream of anything.

It was 2008. My father had been dead for six years. My grandfather had died in 2000 after having a stroke outside a convenience store. My first aunt, she’d lost her life in 1998 due to a hemorrhoid removal operation. My uncle had broken his neck in the summer of 1990, when going for a dive in the river with his friends.

“Both of my parents died in 1989,” Small Bamboo said, “my mother at the beginning of the year because of diabetes; my father at the end of year, in prison.”

“My girlfriend has been dead for ten years now,” Old Stone said. “She struggled with anorexia for years and killed herself in the winter of 1998.”

“You prawns!” Young Li puffed out a mouthful of smoke. “Can we talk about something else★ Haven’t we had enough of dead people★”

“Shall we have a game of mahjong★” Old Stone suggested.

After they left the table, I took out my book and began to read. The TV was on in the next room, and Sister Du and the waitresses were watching the news, weeping.

Six Times wandered over and sat down beside me. “What are you reading★”

I showed him the cover.

“Camus,” he said. “Interesting. Do you like him★”

“He’s all right,” I said.

“You should read Márquez,” he said. “Love in the Time of Cholera is a better choice.”

I put down the book and looked at him. “What are you getting at★”

He smiled shyly. “Vertical and Chilly are having sex in my tent. Shall we go to Vertical’s tent and have sex as well★”

I thought about his proposal for a while. “Okay,” I said.

We walked into Vertical’s tent and removed our clothes. He touched me for a short while before entering. We hugged and moved towards and away from each other repeatedly. I felt cold the whole time because I was lying on the ground. He cried when he came.

Afterwards, we sat outside the tent, sharing a cigarette.

“Four days ago I was a nonsmoker,” I said.

“Five days ago I had no idea there’d be an earthquake,” he said. “What were you doing★”

“I was giving my cat a bath,” I said. “And you★”

“I was trying to fix my laptop,” he said. “How’s your cat★”

“She ran away wet. Hope she’s dry now. How’s your laptop★”

“Dead,” he said.

“I heard earlier on TV,” I said, “that the number of casualties is now sixty-two thousand, three hundred and fifty-seven.”

He took the cigarette and smoked. “You have a good memory.”

The alarm rang sharply across the city again.

Sister Du rushed out of the Little House and shouted: “Another one is coming! The news just said there’s a big aftershock tonight! Magnitude seven point eight to eight. The government is telling us to seek shelter.”

“Relax, cousin,” Small Bamboo said, half-turning from the mahjong table. “We are already in a shelter.”

That night, nobody could sleep. We went into Young Li’s tent and sat down in the living room. It was surreally spacious, furnished with a pair of ivory four-seater leather sofas, one white armchair, and a cream chaise longue. There was even a bookshelf.

Small Bamboo sat down in the armchair. “Bloody hell,” he said, slapping his thigh. “This is a palace.” Young Li and Six Times walked in, carrying a square table. They put it down and flipped up four curved extensions. An enormous round table emerged.

We all stared at it. “Bloody hell,” Small Bamboo said.

“Old Stone asked me to get a big table for dinner,” Young Li said.

“If this is the table we’re sitting at, I’ll need a telescope to see the dishes,” said Chilly.

“When the aftershock comes, we can hide underneath it,” Six Times said, knocking the tabletop.

While Old Stone was busy cooking in the kitchen with Calm—Young Li’s wife—and Sister Du helping out, we talked about him. Apparently, after his girlfriend died, Old Stone immersed himself in the study of how to make the perfect twice-cooked pork. From there, taking it dish by dish, he had become a chef and a reputable food critic. He’d published three books: Love and Lust in Sichuan Cuisine, The Pepper Corn Empire, and The Night We Ate Armadillos. The last one was a collection of poems.

“I actually have the books here.” Young Li stood up and searched on the bookshelf. “Here.” He took a book out, leaned on the bookshelf, and started to read: “★‘When language becomes corrupt, we need to talk about fish. Are fish happy★ someone asked, a long time ago. You have no idea because you’re not a fish. If a tomato knows a fish well…’★”

“Is this the poetry book★” I asked.

“No, it’s his cookbook,” Young Li said, and pushed it back.

Everybody laughed. I laughed with them. We drank beer.

Calm came out from the kitchen, wearing a purple apron on top of the red floral dress. She dropped a stack of bowls and chopsticks on the table and said: “The food is coming.”

We pushed over the sofas and each grabbed a bowl and chopsticks. As we took our seats, Sister Du carried out the starters on a tray and put them down one by one: chicken feet with pickled chilies, fried fish skin with coriander, marinated pig’s tails and thousand-year eggs with green pepper.

The poets cheered and dived in.

“What can Pigeon have★ She’s vegetarian,” Vertical said.

Young Li examined the dishes. “Fish skin★ There’s no meat in it.”

“It’s fine. I’m not really hungry,” I said, and drank my beer.

The starters were gone within minutes and Sister Du delivered more dishes: hot, steaming, and aromatic. Old Stone’s signature twice-cooked pork was served, followed by braised pork belly, stewed pig feet with fermented black bean, sautéed pig kidney and liver, and braised pig knuckles with bamboo shoots.

“Where does he get all this stuff★” Chilly marveled, jabbing a knuckle with his chopsticks.

“Old Stone has connections,” Young Li mumbled between chewing. “Do you know who his father is★”

Chilly shook his head. “No, should I★”

Young Li spat out a bone and disclosed a name that I had learned in my Local History class at elementary school.

“Seriously★” Chilly said.

“Yep.” Small Bamboo nodded. “This prawn could have been sitting in an office in the central government now if he hadn’t got the wrong girlfriend and joined the protest with her at the wrong time.”

“Our generation is just fucked,” Young Li said.

“We’re fucked too,” Chilly said competitively.

They continued arguing while the second round of food was brought out. This time: sliced beef in chili oil, stewed beef brisket in casserole, spiced calf ribs with Sichuan peppercorn, and beef offal soup.

The room was filled with hot steam. I sneezed.

“Can I get you anything★” Vertical said. “Poor Pigeon, you must be starving.”

“I’m fine,” I insisted.

She looked around the table. “How about the soup★ I can get you some soup without offal,” she said.

“Uh, okay,” I said.

She ladled me a bowl of offal-free soup. I stared at it and drank. The soup flew into my mouth and diffused into my guts, like a long, soft exhalation. It made me think of when my grandfather carried me on his back to the cattle market to see the cows. They smelled like manure and peat. Their eyes were the eyes of Buddha. They looked at me.

“Can I have another one★” I said. “With offal, please.”

We were all devouring like wretched beasts. It began to rain outside. The rain fell, drumming the roof with an urgent rhythm while more food was served. We had a round of poultry: chicken, duck, goose, quail, and ostrich; and then six types of fish: rudd, sea bass, mandarin, silver jin, golden chang, and fugu; afterwards some rare delicacies whose names I learned from the others: boar, abalone, soft-shelled turtle, muntjac, and armadillo.

“Bloody hell,” Small Bamboo said, his chopsticks gnashing. The rain fell in torrents.

A group of beautiful women walked out from the kitchen, wearing shiny silk dresses embroidered with pearls. Their hair was embellished with small crowns and colorful feathers, their lips glossily red. Together, they held a huge brass pot, in which a dense and hearty chili stew bubbled, exuding a brawny fragrance of meat, chili pepper, and Chinese five-spice mixture. It was head stew, and had been extremely well cooked so the heads cracked, mushed and melted together—some eyes were missing, some noses crooked, lots of tongues stuck out. They were the heads of men and women.

My stomach turned sharply. I bent and threw up under the table.

The Night We Ate Armadillos

By: Old Stone

About five in the afternoon Small Bamboo asked me

to have dinner with him and his friend Boss Huang.

Huang has got some rare delicacies, he told me.

In a private dining room Huang locked

the door and served us a huge pot of braised

armadillos.

Dig in, said Huang, it’s a first-class national protected animal

so we are all committing crimes together.

Speaking of criminals, said Small Bamboo,

the armadillos were Chairman Mao’s favorite

when he was a guerrilla

in the Jinggang Mountains

back in the old days

The day after the dinner party, a real crisis set in. It had rained so much the previous night that the water had swept through the wreckage, where hundreds of thousands of bodies were still buried, and into the reservoir.

“Now we’ll have to drink skin-flavored water,” Chilly said.

“Ew,” Vertical said.

We were sitting outside the Little House. Old Stone had advised us earlier to relax and not to worry about the water. There were at least eight or nine cartons of beer stocked in the Little House, so we should be well hydrated for another couple of days. “Trust me, before we finish the beer somebody will sort the water out,” he concluded, and went to join Small Bamboo, Young Li, and Calm for a game of mahjong.

The rest of us sat, drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. In the center of the square, a man stood on a table, looking down at the crowd while shouting: “One last ticket to Beijing! The train leaves at ten tonight! Any higher offers★” In the opposite direction, a young nurse held a megaphone, calling: “Volunteers needed! Volunteers needed! The bus leaves at eight a.m. tomorrow at the community medical center!” A group of teenagers chased a boy out of a convenience shop a few doors down. “Give us the milk, you cocksucker!” A woman walked by in front of us, weeping, holding a small child in her arms.

“It’s like watching a movie,” Six Times said.

“I feel troubled that I’m not really sad,” said Chilly.

“I’m not very sad either,” Vertical said. “And you★ Pigeon.”

“I’ve been thinking,” I said slowly. “All of this is great material. But I don’t think I’ll ever write about the earthquake.”

“I’ll never write about it either,” Six Times said.

“And what do we say when many years later people ask us about the big earthquake in 2008★” Vertical said.

“We can talk about the aggressive beer drinking,” Chilly suggested.

“And the sounds of intercourse at night,” Six Times said.

“And the banquet Old Stone cooked for us,” I added.

Vertical turned to me and smiled. “Is everything all right, Pigeon★”

A woman screamed in the square. A tent fell. Some young men shouted loudly.

“What do you mean★” I said.

“You’ve mentioned that dinner a number of times already,” Vertical said. “And you’re reading Old Stone’s poetry book.”

“Young Li lent me the book,” I said. “But I find it difficult to understand.”

“Poetry is not for understanding,” Chilly said.

Six Times downed his beer. “Think about it this way,” he said, “when you write a story, you’re essentially creating a dish. You want people to see the meat and the veg and even to smell the fragrances. But they can’t actually eat it. They can only imagine the taste of the food by interpreting the image of it.”

I thought of yesterday’s dinner again. They all seemed to have forgotten what happened.

“But none of these matter to us,” Six Times continued. “When poets come into the room we simply chomp on the fictional dish you’ve created. We eat up the food and shit it out later. And the shit is poetry.”

Chilly laughed and clapped. Vertical and I laughed as well.

That night, I stayed in Six Times’s tent and we made love like primitives. There were no condoms, so he came on my belly. Later, to help me clean up, he poured some beer on my belly and wiped it off with his socks. I told him I would prefer to have dried sperm on my belly than cold beer and the filth from his socks. He said he was sorry.

Afterwards we slept. A series of magnitude 4 to 5 aftershocks struck, rocking us into deeper sleep. In my dreams I had a conversation about the earthquake. I remembered it clearly even after waking up. My deceased father sat in front of me, his face stained by a thick tawny paste, his nose crooked. And he asked me: “How do you know this is all real and happening★ How can you be sure you haven’t already died in the earthquake and are just living in the afterlife★”

I told Old Stone about my dream and he laughed for quite a while. “That is a very Zhuangzian dream,” he said.

“You could say that about every dream,” I said.

“Have you ever eaten butterflies★” he said. “I haven’t had butterflies per se but once in Kunming I had caterpillars. They were nicely deep-fried, lightly seasoned with chili powder and cumin, and tasted like crispy air.”

We sat outside the Little House, facing the square. Nearly one third of the tents had disappeared, leaving discolored spots on the ground, like the surface of the moon. Young Li’s red tent remained standing.

“How much longer do you think we can last without water★” I asked.

“Not long,” Old Stone said. “But we might surprise ourselves—this morning, a search team dug out a man who’d been buried for more than seventy-two hours, still alive.”

“That’s something,” I said.

“So I suppose the real question is—another Zhuangzian one—do you actually want to live or not★” He continued: “With my girlfriend, I realized she had given up when she lost her appetite. First she said she wasn’t hungry and then she just hated food, couldn’t stand looking at it, smelling it, or even hearing about it. One day we got up, I said, ‘What do you want to have for breakfast★’ and she screamed as if someone had stabbed her with a knife. That was when I knew she’d made up her mind.”

I was about to say something when the others came back in Sister Du’s mini-truck, carrying cardboard boxes and bags of bottled water, instant noodles, and other stuff. Small Bamboo sat down by us, unscrewed the lid from a bottle of water, and gulped down half of it. “Motherfucker!” he said. “I’ll never drink beer again.”

“Where did you get these★” Old Stone asked.

“The community medical center,” Small Bamboo said. “Sister Du heard a new batch of volunteers arrived from Xi’an, so we called over.”

“You prawns,” Old Stone said. “These are for the victims of the earthquake.”

Young Li sat down and started taking cartons of cigarettes out of his box. “We are the victims,” he said. “We’re all enduring.”

A man walked by. Young Li whistled and threw him a bottle of water and a carton of cigarettes. The man caught them swiftly and went away.

Later, Chilly, Vertical, Six Times, and I sat by the flower bed, eating tins of braised pork and sweet chili fish.

“These are not very good,” Chilly said, exerting himself to swallow.

“Xi’an people don’t know how to cook. They live only on noodles,” Six Times said.

“Taste fine to me,” I said.

Six Times turned around. “Since when are you eating meat★”

“I think Pigeon has a crush on Old Stone,” Vertical said.

They all looked at me and I said: “What★”

“You’re reading his book all the time. You put it right beside our pillow,” Six Times said.

“Because I’m trying to understand poetry,” I said. “Plus, I finished Camus.”

“Can I have Camus★ I’ve always wanted to read The Plague,” Chilly said.

We then talked about The Plague and The Myth of Sisyphus, drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. Not far from us, Old Stone, Small Bamboo, Young Li, and Calm were playing mahjong on a square table. Calm wore a green cardigan on top of the red floral dress. She hurrahed, pushed down her tiles, and clapped. The three men handed over their money. The others were watching TV inside the Little House. The volume was loud, announcing that the government was installing a new water filtration system in the reservoir. “…We are fighting minutes and snatching seconds,” it said.

For the first time in many years, I felt a tingling of contentment. I ate meat and drank water. I had a bed to sleep in. Before long, I would go to my bed and have a dream about butterflies, and, just like Zhuangzi, I would not be able to tell if it was me who dreamed about the butterflies or a butterfly who dreamed about me.

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (July 11, 2023)

- Length: 304 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982198480

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

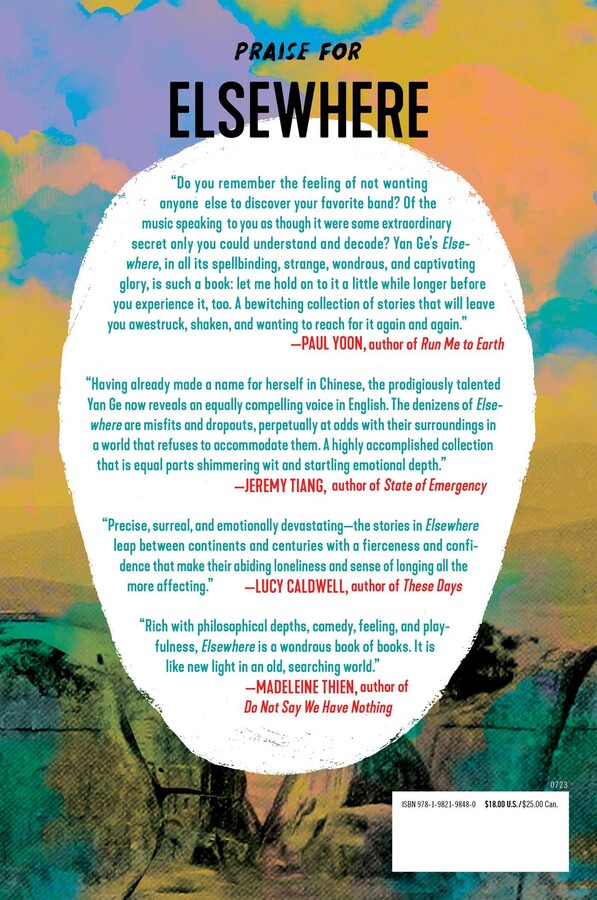

Praise for Elsewhere

"The linked entries in Yan Ge’s deft English-language debut, Elsewhere, explore the power of language across the Chinese diaspora to either bring people together or push them apart.”—The New York Times

"With wry humor and occasional earthy surrealism, Yan Ge... delicately renders both the linguistic and physical manifestations of longing."—The New Yorker

"What’s consistent…is an abiding sense of lightness, even when the characters are melancholy or lost….The pleasure of traveling ‘elsewhere,’ as in reading this singular book, is in wandering.”—Wall Street Journal

"Yan Ge applies her trademark stylistic prowess to bitesize stories, which follow protagonists as they navigate the sense of otherness with varying degrees of success. Pour a crisp glass of something and settle in for a ride, it’ll be time well spent."—Rolling Stone

"The English-language debut from celebrated author Yan Ge is a genre-bending short story collection that’s as haunting, dreamlike, and addictive as a melatonin-induced slumber."—Nylon

"Jangly and eclectic... These stories map out the distance between the head and the gut—the way language can fail to convey the deepest, most visceral facts of life."—The Guardian

"Yan Ge folds sentimentality, ritual, and banality into an offbeat chronicle of lonely people trying to sustain themselves in strange new roles and tongues, learning how to feed themselves through layers of dysfunction and dyspepsia.”—The Drift

"This subtle but brilliant collection will draw readers in and keep them enchanted until the very last word."—Booklist

"Yan Ge explores human connections and disruptions in this ethereal collection… Here and elsewhere, Yan combines dry and subtle humor with her evocative lyrical style. These stories brim with intelligence.”—Publisher's Weekly

"A bold, confident book that delights in written language even as it probes it.”—Kirkus

"Do you remember the feeling of not wanting anyone else to discover your favorite band? Of the music speaking to you as though it were some extraordinary secret only you could understand and decode? Yan Ge’s Elsewhere, in all its spellbinding, strange, wondrous and captivating glory, is such a book: let me hold on to it a little while longer before you experience it too. A bewitching collection of stories that will leave you awestruck, shaken, and wanting to reach for it again and again."—Paul Yoon, author of Run Me to Earth

“A gripping, stunning work, worldly and otherworldly. Rich with philosophical depths, comedy, feeling and playfulness, Elsewhere is a wondrous book of books. It is like new light in an old, searching world.”—Madeleine Thein, author of Do Not Say We Have Nothing

“Yan Ge is one of the most surprising writers I’ve read in recent years, a fantastic storyteller who never fails to thrill me. In Elsewhere, her stories are both expansive and precise, their range of subjects and approaches suggesting few bounds to the subversive pleasures her stories might deliver. I suspect that even now Yan Ge is racing ahead of us lucky readers, off to explore the outer limits of possibility.” —Matt Bell, author of Appleseed

“Having already made a name for herself in Chinese, the prodigiously talented Yan Ge now reveals an equally compelling voice in English. The denizens of Elsewhere are misfits and dropouts, perpetually at odds with their surroundings in a world that refuses to accommodate them. A highly accomplished collection that is equal parts shimmering wit and startling emotional depth.”—Jeremy Tiang, author of State of Emergency

"Precise, surreal and emotionally devastating—the stories in Elsewhere leap between continents and centuries with a fierceness and confidence that makes their abiding loneliness and sense of longing all the more affecting."—Lucy Caldwell, author of These Days

"I don’t know anyone who writes like Yan Ge. In her distinctive story collection, Elsewhere, we meet characters from everywhere: the ancient world and the present day, the East and the West, the all-too-human and the larger-than-life. Throughout, we are confronted with questions simultaneously playful and profound, graced with dry wit and a blink-and-you-miss-it humour. Yan Ge writes with impressive facility across many registers, embracing a breadth of topics with both irreverence and pathos. Quick to read, but long to consider, I think this collection is extraordinary. "—Melissa Fu, author of Peach Blossom Spring

Praise for Strange Beasts of China

"The atmosphere of Strange Beasts of China is delightful. Through the narrator’s futile quest to catalog beasts, Yan captures the fluidness of city life, the way urban space defies definition even for people hellbent on making sense of it."

—The New York Times

Luminous and beguiling… Yan is a deft and engaging storyteller, with a proclivity for dramatic revelations… Yan’s rare versatility and inventiveness keeps the narrative continuously surprising. … Strange Beasts transfixes you like a vivid dream, offering glimpses of the waking world contorted into uncanny forms.”

—The Washington Post

“Magical realism of the best kind, where the spectacular is paired with just enough irony and daffy humor to keep it grounded on earth—or whichever world this fun and beguiling book takes place.”

—The Wall Street Journal

“A page-turner whose dense, fantastical atmosphere lingers long after the read.”

—Vulture

“Strange Beasts of China feels like a riddle and a parable and a dream, the kind of book you want to get lost in.”

—The Philadelphia Inquirer

"A thought-provoking read on its own merit, the book takes on added significance given that it is an early work by Yan, whose talent is clear, raw and electrifying."

—Post Magazine

"Playful and darkly subtle . . . The world shown here is full of chaos and vulnerability."

—The Irish Times

“Mixes a sort of Borgesian bestiary of mysterious creatures with a deep sense of urban andsocial alienation to produce an enthralling and fascinating narrative. A breath of fresh air in theoften hard-sf dominated field of recently translated Chinese science fiction, this novel is a must-read for fans of Vandermeer, Borges, or fantasy fiction that blurs the line between genre and literary fiction.”

—Booklist (starred review)

“The overall effect of Yan’s storytelling is dreamy and hypnotic, sometimes opaque but always captivating. These cryptic but well-told tales offer much to chew on.”

—Publisher’s Weekly

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Elsewhere Hardcover 9781982198480

- Author Photo (jpg): Yan Ge Photograph by Joanna Millington(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit