Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

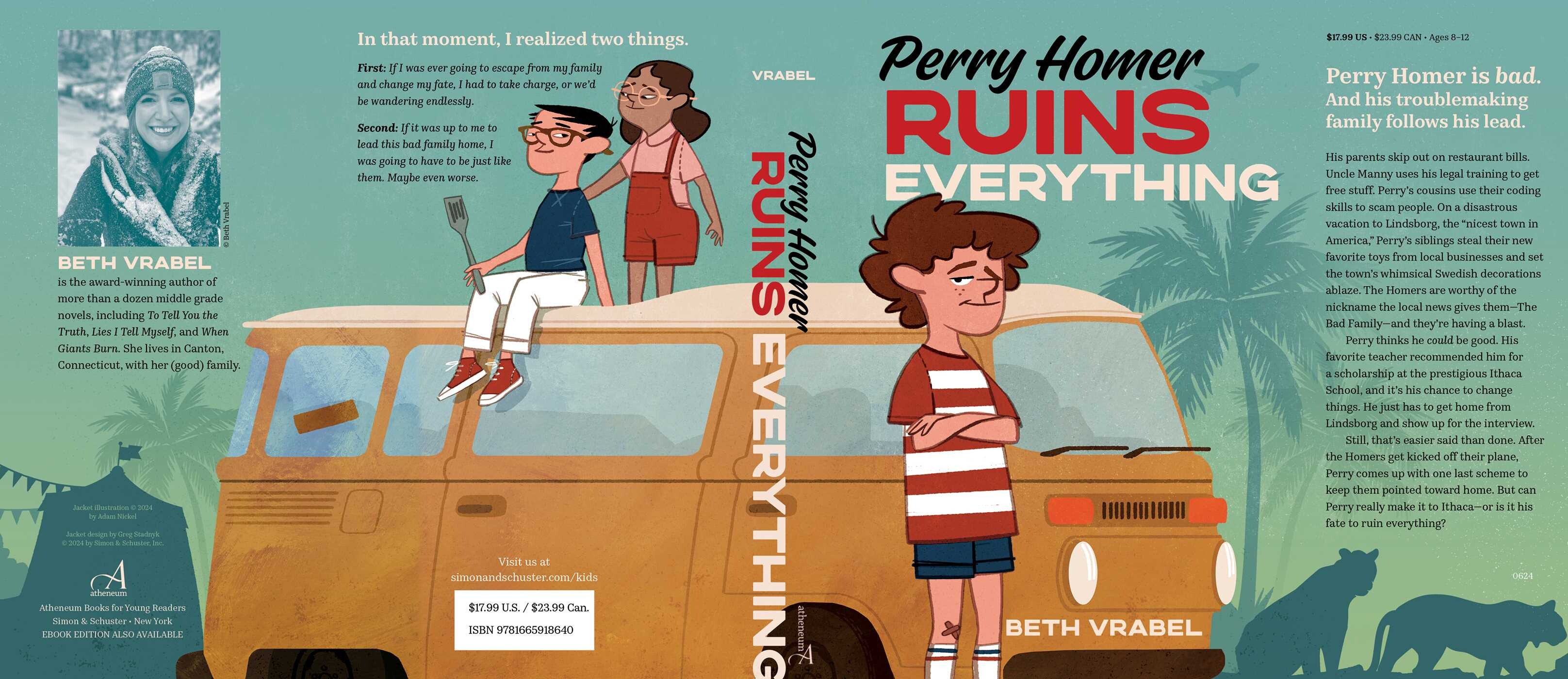

About The Book

In this funny, hijinks-filled middle grade romp, a boy and his con artist family’s rascally ways keep them on a never-ending vacation full of rip-offs and schemes, leaving him to wonder if it’s too late to change his fate.

Perry Homer is bad news, just like the rest of his troublemaking family. His parents skip out on restaurant bills. Uncle Manny uses his legal training to get free stuff. Perry’s cousins use their coding skills to scam people. On a disastrous vacation to Lindsborg, “the nicest town in America,” Perry’s siblings steal their new favorite toys from local businesses and set the town’s whimsical Swedish decorations ablaze. The Homers are worthy of the nickname the local news gives them—the Bad Family—and they’re having a blast.

Perry thinks he could be good. His favorite teacher, Miss Penelope, recommended him for a scholarship at the prestigious Ithaca School, and it’s his chance to change things. He just has to get home from Lindsborg and show up for the interview.

Still, that’s easier said than done. After the Homers get kicked off their plane, Perry comes up with one last scheme to keep them pointed toward home. But can Perry really make it to Ithaca—or is it his fate to ruin everything?

Perry Homer is bad news, just like the rest of his troublemaking family. His parents skip out on restaurant bills. Uncle Manny uses his legal training to get free stuff. Perry’s cousins use their coding skills to scam people. On a disastrous vacation to Lindsborg, “the nicest town in America,” Perry’s siblings steal their new favorite toys from local businesses and set the town’s whimsical Swedish decorations ablaze. The Homers are worthy of the nickname the local news gives them—the Bad Family—and they’re having a blast.

Perry thinks he could be good. His favorite teacher, Miss Penelope, recommended him for a scholarship at the prestigious Ithaca School, and it’s his chance to change things. He just has to get home from Lindsborg and show up for the interview.

Still, that’s easier said than done. After the Homers get kicked off their plane, Perry comes up with one last scheme to keep them pointed toward home. But can Perry really make it to Ithaca—or is it his fate to ruin everything?

Excerpt

Chapter One One

ITHACA SCHOOL INTERVIEW QUESTION 1:

Tell us about a meaningful relationship in your life.

Come home, Perry. As soon as you can.

I swallowed as I punched out a reply to the text. I’m trying, Miss Penelope.

“You know,” the old woman sitting next to me on the airplane said as she nudged me with her bony elbow, “it’s time to put away your phone.”

I flashed her a quick smile and tucked my phone into my back pocket. The woman’s cheeks flushed, and her mouth twitched. Mom says I have a megawatt smile—and that God only gives such a smile to people whom he intends to use it for good. Their own good, of course. For a long time after Mom told me that, I didn’t smile at all. I still try not to whenever I can help it, just in case.

“You look like a fine, smart-looking fellow,” the woman said as she tightened her buckle. She was worried about the flight; I could see it in the way her hands shook as she zipped up her bag, the way her eyes darted down the aisle tracking the flight attendants, and in how she smoothed her hands over her pant legs every few seconds. “How old are you?”

“I’ll be fourteen in December,” I told her.

“That’s more than half a year away. You should simply say you’re thirteen. Are you traveling alone?” She held up a hand before I could reply. “Don’t answer that. It isn’t safe to say if you are traveling alone.”

Alone. At that moment, someone in the back of the plane yelped. My little brother, Pauly. “Stop looking at me, Riley!” he shouted, followed quickly by a thud. That would be my sister. Nine-year-old Riley didn’t speak—no one knew why—but she managed to communicate, nonetheless. Pauly was sandwiched between us in age at ten. The baby, strapped to Mom’s chest, had been a surprise, which might be why no one had gotten around to naming her yet.

“Stop it! Stop it, yinz!” came another shout, this one from my dad. “Riley, stop! Stop! Don’t bite!”

I swallowed, trying to focus on the old lady’s question. Man, what I would give to be traveling alone.

A flight attendant hurried down the aisle toward my brother and sister. Another squeezed past her as she trotted to the front of the plane, where Uncle Manny was gesturing for a Bloody Mary. “Sir,” the flight attendant called, her voice tight and irritated, not that Uncle Manny would notice. That’s how everyone speaks to him. “This isn’t a restaurant. You can’t snap your fingers and expect me to show up.”

“How convenient, then, that you’re here.” He held up his empty cup. I didn’t have to be facing him to know he winked at her too. He’s always winking. I don’t think he even knows he does it anymore. The overhead light shone down on his shiny scalp where he missed spraying it with the brown gunk that he is sure tricks everyone into thinking he has a full head of hair. “I’ll have another.”

“We’re not doing drink service until we’re in the air,” the attendant said, and crossed her arms.

Uncle Manny groaned. “I’ve already been flying for four hours!” He slumped back against the seat. Uncle Manny looks like what would happen if you took the arms off a gorilla and stitched them onto the body of an accountant.

The old woman shook her head. “Some people.” She sighed. “Well, I’m glad I’m not sitting next to one of them.”

“You and me both,” I said, and the truth of it was like a blanket over me. In a few hours, I’d be back in Pennsylvania. This whole horrible “summer vacation” Uncle Manny had won to Kansas would be behind us, along with the reporters who had trailed us since “the small, insignificant fire incident.” (Mom’s words. The fire chief’s version was “structure entirely engulfed in flames.”) Dad had traded in our direct flight tickets for free meals at the airport, which is why we were now in South Carolina, waiting for our connecting flight to Pittsburgh.

Mom and Dad, Pauly, Riley, the baby, Uncle Manny, my triplet cousins, and I would pile in the transport van at the airport parking lot and head home. But the next day? I’d meet with Miss Penelope and prepare for my interview at the Ithaca School for Scholars in New York. I had almost three months until August, when I’d have to sit in front of the selection committee for the scholarship. While Ithaca School let me know I had been accepted back in March, that didn’t matter if I didn’t get one of the full-ride spots. My folks had trouble scrounging up rent money; paying for tuition wasn’t going to happen. Maybe three months sounds like a long time to prepare for one interview, but Miss Penelope assured me it was not. “The interview is vital, Perry,” she told me.

Miss Penelope believed I could do it. I could win a scholarship. So that meant, for the most part, I believed it too. This trip was my last hurrah with my family. I would leave them and the worse version of me behind when I went to Ithaca, where I’d be honest Good Perry, someone who used everything he had—smiles, brains, and all—not to take advantage of people but to make them, especially Miss Penelope, proud. Maybe even make them better. “I’m heading home to my boarding school in New York,” I said to the woman even though I had never been to the school in person, the term didn’t start until September, and I hadn’t technically been awarded the full scholarship I needed to attend. Yet.

She nodded. “I’m going to Pittsburgh to visit my new grandbaby.” She tugged the corner of her bag out from under her seat and pulled out her phone. “This is my Andy,” she said as she showed me a picture on her screen of a chubby baby with a drooly, splotchy face. “My name’s Minerva.”

“Ah,” I said as I took in the picture. Now, my baby sister, squawking in a row behind me in Mom’s arms, was no Gerber model, but poor Andy looked more like a potato than a baby, especially if that potato had a mouth and someone had squirted pickle juice inside of it. “Congratulations, Miss Minerva. What a baby!”

“And what a nice boy you are!” She patted my hand with her soft, wrinkled fingers. “I have something special for you.” Minerva tucked over her seat again. She put away her phone but also opened her wallet. Rifling through it, she then sat upright and handed me a coin.

“Wow,” I said. “A penny. Thanks.”

Minerva winked at me. “It’ll give you luck.”

I rubbed my thumb at the penny and then stared at it a little closer as Minerva tossed her wallet back into her bag. She missed. I covered the wallet with my foot and slid it under my bag. Now, don’t go looking at me like that. I wasn’t going to steal it. (My brother, he’d be the one to watch when it comes to sticky fingers.) Mom says I have a knack for spotting jobortunities. To put it in a prep school way: I note circumstances a person of lesser ethics might exploit. I sat for a minute with the wallet under my shoe. Dad calls this moment “the rush.” It takes a person over, your whole body moving in every direction so quickly it looks like standing still, being calm. It’s every single bit of you recognizing that you’re not following the rules. That you do what you want, take what you can. I think it feels like power, not that I’ve ever had any for real.

I pulled in a big breath, letting the rush work through me, then bent over and swiped the wallet out from under my foot. “I think you dropped this, ma’am.”

“Oh!” Minerva said. “What a good boy you are!”

I swallowed her praise, glad Mom and Dad weren’t close enough to hear it. I wanted to be a good person. Miss Penelope thought I could be. Maybe that’s why this interview prompt made me think of her and not anyone in my family. Because of her, I was almost convinced that I could be a good person. Despite being part of the Homer family.

The speaker system pinged and then a crinkly voice echoed through the cabin. “This is Captain Gerty speaking. The skies are clear, and runway open for our flight to Pittsburgh. I hope you all enjoyed your time in South Carolina!”

“Hah!” I heard from the back of the plane. That’d be Mom. “That’s as terrible as the last flight, where they said, ‘Thank you for visiting Kansas.’ What a joke!”

“Flight attendants,” continued Captain Gerty, “prepare for takeoff.”

“Did you have a nice visit in South Carolina?” Minerva asked me.

“Well, we were only here for an hour, but it was okay,” I said. “We were in Kansas before that for about a week.”

“Kansas!” Minerva exclaimed. “I grew up there. Which part did you visit?”

“Lindsborg.”

“Ah! Lindsborg!” Minerva was an exclaimer, I guess. Everything I said seemed to delight her. “Such a lovely spot. You know, it was voted the friendliest town in the United States.”

I kept my face smooth, even as my brain flashed to our last moments in Lindsborg, a small town famous for its cheery Swedish heritage. When we arrived, townspeople in embroidered dresses had greeted us. “Välkommen till Lindsborg!” they called, putting flower crowns on our heads. As we left, the same maidens ran down the streets, fists raised, chasing us as their maypole toppled, their huge wooden Dala horse blazed, and sirens blared.

“Yeah,” I said now. “Great town.”

Minerva’s forehead wrinkled. “You know, I remember hearing something about Lindsborg on the news! Some horrible people going through it after winning a contest of some sort.” She tilted her head to the side and looked up, as though the ceiling would help her remember. “Terrible,” she said as she met my gaze again. “An entire family full of thieves, stiffing restaurants, burning the park, running amok.”

“I’m sure it wasn’t the entire family,” I muttered, but Minerva didn’t seem to hear me. “And I heard it was an all-expenses-paid vacation.…”

“One of them was barely clothed!”

“Barely clothed, you say?” I shifted in my seat. The price tag on the shirt scratched the back of my neck.

“Yes,” Minerva said as she leaned toward me. “Born into a bad family. I mean, who lets their kid run around shirtless like that?”

“Maybe it was a misunderstanding? Like, maybe his mom said she packed a bunch of shirts, but really the only shirt he had was the one he was wearing, and then his baby sister puked on that shirt, but no one would take him to Target for a new one, and it was either go shirtless or wear one of his cousins’ terrible shirts that could double as a dress,” I said. “Or something like that.”

“What a vivid imagination you have,” Minerva said. “They said the youngest boy threw a firecracker toward their biggest Dala horse, setting it ablaze! The local council had to run them all out of town.”

“Huh,” I murmured. “Maybe the kid tripped? Maybe he didn’t mean to kick it toward the horse?”

Minerva snorted. “And he accidentally lit it first too?”

I pressed my back against the seat, deliberately not looking toward Pauly. The truth was, he did light the firecracker, using a lighter someone had dropped in the street. But he hadn’t expected it to work, and then he panicked, kicked it, and… well, who knew that Dala horse would be so flammable?

A flight attendant held up her hands. “Back to your seat! Back to your seat!”

Minerva twisted her neck, eyes bulging and mouth popping open.

“Aaaaaargh!” That would be Riley. More screams rang out and then my little sister, mouth open in a wail like a small Amazonian warrior, tore down the center aisle hoisting Pauly’s most prized possession—a huge black plastic spatula—over her head with Pauly on her heels swinging a ratty old teddy bear. When I said Riley didn’t speak, I meant words. She was top-notch at screeching.

The flight attendant grabbed Riley, still screaming, around the waist. That was enough to shift Pauly’s loyalty. He dropped the bear, which made Riley wail even louder (it was her bear), and kicked the flight attendant in the shin. “Put down my sister!”

The flight attendant dropped Riley and landed on the floor with a thump, grasping her shin. “What’s the matter with you, kid? I wasn’t hurting her!”

I didn’t even realize I was out of my seat, my mind entirely snagged on the attendant dropping my sister, until Minerva tugged on my shirt. “Sit down, son,” she said. “Best to let the adults handle that.”

Riley grabbed the bear off the floor, hit the attendant with it, and ran back toward Mom.

“Hey, now!” Oh, great. Dad was entering the aisle. I sat back down. Dad shimmied sideways down the row. He turned toward the other passengers, most of whom were now directing their phone cameras toward him. Dad noticed, straightening his back and combing his thin hair with his fingers. He pushed his dark sunglasses up his nose. Dad doesn’t like people to see his eyes. He says he prefers an air of mystery. “You all see how this airline treats children? We demand an upgrade!”

“An upgrade?” the flight attendant howled, standing on one leg to cradle her shin in her hand. “He kicked me!”

“Who you calling a brat?” Mom jumped to her feet. No one had, in fact, called Pauly a brat. At least, not out loud. The baby, strapped to Mom’s chest, gummed her fist. The cell phone cameras swung toward the back of the plane. Uncle Manny ducked into his chair.

That seemed like a good move. “I’ve always wanted a window seat,” I whispered to Minerva, pointing to the empty seat beside her. “Mind if I—” Minerva didn’t blink, eyes on the show. I unbuckled and squeezed past her, sliding my backpack over her feet. I slumped low in the seat, eyes out the window. The notebook in my back pocket jabbed at my hip. The admissions paperwork in my backpack crinkled as I moved.

Come home, Perry. As soon as you can.

ITHACA SCHOOL INTERVIEW QUESTION 1:

Tell us about a meaningful relationship in your life.

Come home, Perry. As soon as you can.

I swallowed as I punched out a reply to the text. I’m trying, Miss Penelope.

“You know,” the old woman sitting next to me on the airplane said as she nudged me with her bony elbow, “it’s time to put away your phone.”

I flashed her a quick smile and tucked my phone into my back pocket. The woman’s cheeks flushed, and her mouth twitched. Mom says I have a megawatt smile—and that God only gives such a smile to people whom he intends to use it for good. Their own good, of course. For a long time after Mom told me that, I didn’t smile at all. I still try not to whenever I can help it, just in case.

“You look like a fine, smart-looking fellow,” the woman said as she tightened her buckle. She was worried about the flight; I could see it in the way her hands shook as she zipped up her bag, the way her eyes darted down the aisle tracking the flight attendants, and in how she smoothed her hands over her pant legs every few seconds. “How old are you?”

“I’ll be fourteen in December,” I told her.

“That’s more than half a year away. You should simply say you’re thirteen. Are you traveling alone?” She held up a hand before I could reply. “Don’t answer that. It isn’t safe to say if you are traveling alone.”

Alone. At that moment, someone in the back of the plane yelped. My little brother, Pauly. “Stop looking at me, Riley!” he shouted, followed quickly by a thud. That would be my sister. Nine-year-old Riley didn’t speak—no one knew why—but she managed to communicate, nonetheless. Pauly was sandwiched between us in age at ten. The baby, strapped to Mom’s chest, had been a surprise, which might be why no one had gotten around to naming her yet.

“Stop it! Stop it, yinz!” came another shout, this one from my dad. “Riley, stop! Stop! Don’t bite!”

I swallowed, trying to focus on the old lady’s question. Man, what I would give to be traveling alone.

A flight attendant hurried down the aisle toward my brother and sister. Another squeezed past her as she trotted to the front of the plane, where Uncle Manny was gesturing for a Bloody Mary. “Sir,” the flight attendant called, her voice tight and irritated, not that Uncle Manny would notice. That’s how everyone speaks to him. “This isn’t a restaurant. You can’t snap your fingers and expect me to show up.”

“How convenient, then, that you’re here.” He held up his empty cup. I didn’t have to be facing him to know he winked at her too. He’s always winking. I don’t think he even knows he does it anymore. The overhead light shone down on his shiny scalp where he missed spraying it with the brown gunk that he is sure tricks everyone into thinking he has a full head of hair. “I’ll have another.”

“We’re not doing drink service until we’re in the air,” the attendant said, and crossed her arms.

Uncle Manny groaned. “I’ve already been flying for four hours!” He slumped back against the seat. Uncle Manny looks like what would happen if you took the arms off a gorilla and stitched them onto the body of an accountant.

The old woman shook her head. “Some people.” She sighed. “Well, I’m glad I’m not sitting next to one of them.”

“You and me both,” I said, and the truth of it was like a blanket over me. In a few hours, I’d be back in Pennsylvania. This whole horrible “summer vacation” Uncle Manny had won to Kansas would be behind us, along with the reporters who had trailed us since “the small, insignificant fire incident.” (Mom’s words. The fire chief’s version was “structure entirely engulfed in flames.”) Dad had traded in our direct flight tickets for free meals at the airport, which is why we were now in South Carolina, waiting for our connecting flight to Pittsburgh.

Mom and Dad, Pauly, Riley, the baby, Uncle Manny, my triplet cousins, and I would pile in the transport van at the airport parking lot and head home. But the next day? I’d meet with Miss Penelope and prepare for my interview at the Ithaca School for Scholars in New York. I had almost three months until August, when I’d have to sit in front of the selection committee for the scholarship. While Ithaca School let me know I had been accepted back in March, that didn’t matter if I didn’t get one of the full-ride spots. My folks had trouble scrounging up rent money; paying for tuition wasn’t going to happen. Maybe three months sounds like a long time to prepare for one interview, but Miss Penelope assured me it was not. “The interview is vital, Perry,” she told me.

Miss Penelope believed I could do it. I could win a scholarship. So that meant, for the most part, I believed it too. This trip was my last hurrah with my family. I would leave them and the worse version of me behind when I went to Ithaca, where I’d be honest Good Perry, someone who used everything he had—smiles, brains, and all—not to take advantage of people but to make them, especially Miss Penelope, proud. Maybe even make them better. “I’m heading home to my boarding school in New York,” I said to the woman even though I had never been to the school in person, the term didn’t start until September, and I hadn’t technically been awarded the full scholarship I needed to attend. Yet.

She nodded. “I’m going to Pittsburgh to visit my new grandbaby.” She tugged the corner of her bag out from under her seat and pulled out her phone. “This is my Andy,” she said as she showed me a picture on her screen of a chubby baby with a drooly, splotchy face. “My name’s Minerva.”

“Ah,” I said as I took in the picture. Now, my baby sister, squawking in a row behind me in Mom’s arms, was no Gerber model, but poor Andy looked more like a potato than a baby, especially if that potato had a mouth and someone had squirted pickle juice inside of it. “Congratulations, Miss Minerva. What a baby!”

“And what a nice boy you are!” She patted my hand with her soft, wrinkled fingers. “I have something special for you.” Minerva tucked over her seat again. She put away her phone but also opened her wallet. Rifling through it, she then sat upright and handed me a coin.

“Wow,” I said. “A penny. Thanks.”

Minerva winked at me. “It’ll give you luck.”

I rubbed my thumb at the penny and then stared at it a little closer as Minerva tossed her wallet back into her bag. She missed. I covered the wallet with my foot and slid it under my bag. Now, don’t go looking at me like that. I wasn’t going to steal it. (My brother, he’d be the one to watch when it comes to sticky fingers.) Mom says I have a knack for spotting jobortunities. To put it in a prep school way: I note circumstances a person of lesser ethics might exploit. I sat for a minute with the wallet under my shoe. Dad calls this moment “the rush.” It takes a person over, your whole body moving in every direction so quickly it looks like standing still, being calm. It’s every single bit of you recognizing that you’re not following the rules. That you do what you want, take what you can. I think it feels like power, not that I’ve ever had any for real.

I pulled in a big breath, letting the rush work through me, then bent over and swiped the wallet out from under my foot. “I think you dropped this, ma’am.”

“Oh!” Minerva said. “What a good boy you are!”

I swallowed her praise, glad Mom and Dad weren’t close enough to hear it. I wanted to be a good person. Miss Penelope thought I could be. Maybe that’s why this interview prompt made me think of her and not anyone in my family. Because of her, I was almost convinced that I could be a good person. Despite being part of the Homer family.

The speaker system pinged and then a crinkly voice echoed through the cabin. “This is Captain Gerty speaking. The skies are clear, and runway open for our flight to Pittsburgh. I hope you all enjoyed your time in South Carolina!”

“Hah!” I heard from the back of the plane. That’d be Mom. “That’s as terrible as the last flight, where they said, ‘Thank you for visiting Kansas.’ What a joke!”

“Flight attendants,” continued Captain Gerty, “prepare for takeoff.”

“Did you have a nice visit in South Carolina?” Minerva asked me.

“Well, we were only here for an hour, but it was okay,” I said. “We were in Kansas before that for about a week.”

“Kansas!” Minerva exclaimed. “I grew up there. Which part did you visit?”

“Lindsborg.”

“Ah! Lindsborg!” Minerva was an exclaimer, I guess. Everything I said seemed to delight her. “Such a lovely spot. You know, it was voted the friendliest town in the United States.”

I kept my face smooth, even as my brain flashed to our last moments in Lindsborg, a small town famous for its cheery Swedish heritage. When we arrived, townspeople in embroidered dresses had greeted us. “Välkommen till Lindsborg!” they called, putting flower crowns on our heads. As we left, the same maidens ran down the streets, fists raised, chasing us as their maypole toppled, their huge wooden Dala horse blazed, and sirens blared.

“Yeah,” I said now. “Great town.”

Minerva’s forehead wrinkled. “You know, I remember hearing something about Lindsborg on the news! Some horrible people going through it after winning a contest of some sort.” She tilted her head to the side and looked up, as though the ceiling would help her remember. “Terrible,” she said as she met my gaze again. “An entire family full of thieves, stiffing restaurants, burning the park, running amok.”

“I’m sure it wasn’t the entire family,” I muttered, but Minerva didn’t seem to hear me. “And I heard it was an all-expenses-paid vacation.…”

“One of them was barely clothed!”

“Barely clothed, you say?” I shifted in my seat. The price tag on the shirt scratched the back of my neck.

“Yes,” Minerva said as she leaned toward me. “Born into a bad family. I mean, who lets their kid run around shirtless like that?”

“Maybe it was a misunderstanding? Like, maybe his mom said she packed a bunch of shirts, but really the only shirt he had was the one he was wearing, and then his baby sister puked on that shirt, but no one would take him to Target for a new one, and it was either go shirtless or wear one of his cousins’ terrible shirts that could double as a dress,” I said. “Or something like that.”

“What a vivid imagination you have,” Minerva said. “They said the youngest boy threw a firecracker toward their biggest Dala horse, setting it ablaze! The local council had to run them all out of town.”

“Huh,” I murmured. “Maybe the kid tripped? Maybe he didn’t mean to kick it toward the horse?”

Minerva snorted. “And he accidentally lit it first too?”

I pressed my back against the seat, deliberately not looking toward Pauly. The truth was, he did light the firecracker, using a lighter someone had dropped in the street. But he hadn’t expected it to work, and then he panicked, kicked it, and… well, who knew that Dala horse would be so flammable?

A flight attendant held up her hands. “Back to your seat! Back to your seat!”

Minerva twisted her neck, eyes bulging and mouth popping open.

“Aaaaaargh!” That would be Riley. More screams rang out and then my little sister, mouth open in a wail like a small Amazonian warrior, tore down the center aisle hoisting Pauly’s most prized possession—a huge black plastic spatula—over her head with Pauly on her heels swinging a ratty old teddy bear. When I said Riley didn’t speak, I meant words. She was top-notch at screeching.

The flight attendant grabbed Riley, still screaming, around the waist. That was enough to shift Pauly’s loyalty. He dropped the bear, which made Riley wail even louder (it was her bear), and kicked the flight attendant in the shin. “Put down my sister!”

The flight attendant dropped Riley and landed on the floor with a thump, grasping her shin. “What’s the matter with you, kid? I wasn’t hurting her!”

I didn’t even realize I was out of my seat, my mind entirely snagged on the attendant dropping my sister, until Minerva tugged on my shirt. “Sit down, son,” she said. “Best to let the adults handle that.”

Riley grabbed the bear off the floor, hit the attendant with it, and ran back toward Mom.

“Hey, now!” Oh, great. Dad was entering the aisle. I sat back down. Dad shimmied sideways down the row. He turned toward the other passengers, most of whom were now directing their phone cameras toward him. Dad noticed, straightening his back and combing his thin hair with his fingers. He pushed his dark sunglasses up his nose. Dad doesn’t like people to see his eyes. He says he prefers an air of mystery. “You all see how this airline treats children? We demand an upgrade!”

“An upgrade?” the flight attendant howled, standing on one leg to cradle her shin in her hand. “He kicked me!”

“Who you calling a brat?” Mom jumped to her feet. No one had, in fact, called Pauly a brat. At least, not out loud. The baby, strapped to Mom’s chest, gummed her fist. The cell phone cameras swung toward the back of the plane. Uncle Manny ducked into his chair.

That seemed like a good move. “I’ve always wanted a window seat,” I whispered to Minerva, pointing to the empty seat beside her. “Mind if I—” Minerva didn’t blink, eyes on the show. I unbuckled and squeezed past her, sliding my backpack over her feet. I slumped low in the seat, eyes out the window. The notebook in my back pocket jabbed at my hip. The admissions paperwork in my backpack crinkled as I moved.

Come home, Perry. As soon as you can.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (June 18, 2024)

- Length: 304 pages

- ISBN13: 9781665918640

- Ages: 8 - 12

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"An amusing story that asks readers to engage with moral gray areas."

– Kirkus Reviews

Awards and Honors

- Junior Tome Society It List

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Perry Homer Ruins Everything Hardcover 9781665918640

- Author Photo (jpg): Beth Vrabel Photograph © Beth Vrabel(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit