Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

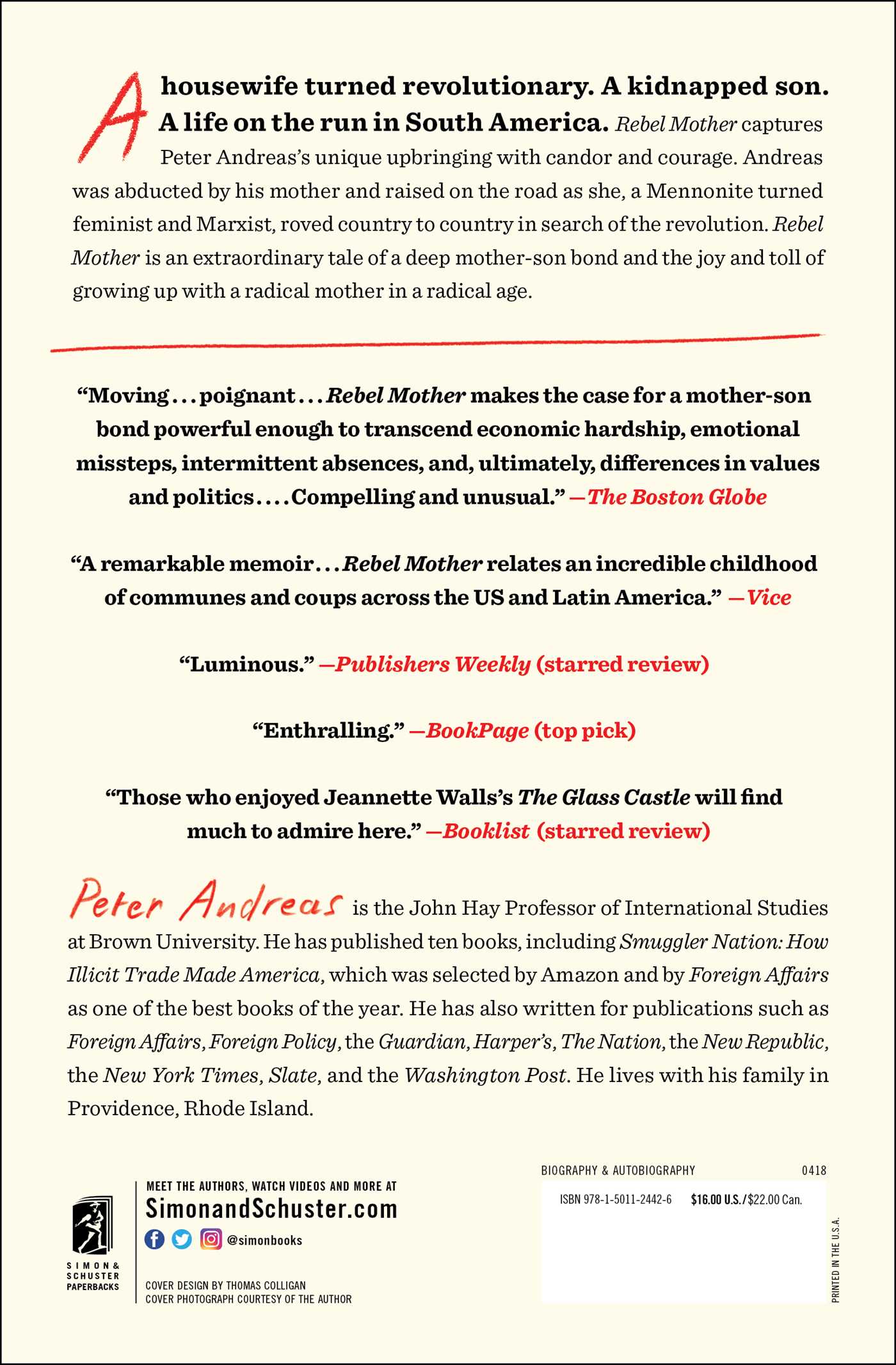

“Those who enjoyed Jeannette Walls’s The Glass Castle will find much to admire” (Booklist, starred review) in this “thoroughly engrossing” (The New York Times Book Review) memoir about a boy on the run with his mother, as she abducts him to Latin America in search of the revolution.

Carol Andreas was a traditional 1950s housewife from a small Mennonite town in central Kansas who became a radical feminist and Marxist revolutionary. From the late sixties to the early eighties, she went through multiple husbands and countless lovers while living in three states and five countries. She took her youngest son, Peter, with her wherever she went, even kidnapping him and running off to South America after his straitlaced father won a long and bitter custody fight.

They were chasing the revolution together, though the more they chased it the more distant it became. They battled the bad “isms” (sexism, imperialism, capitalism, fascism, consumerism), and fought for the good “isms” (feminism, socialism, communism, egalitarianism). Between the ages of five and eleven, Peter lived in more than a dozen homes, moving from the comfortably bland suburbs of Detroit to a hippie commune in Berkeley to a socialist collective farm in pre-military coup Chile to highland villages and coastal shantytowns in Peru. When they secretly returned to America they settled down clandestinely in Denver, where his mother changed her name to hide from his father.

A “luminous memoir” (Publishers Marketplace, starred review) and “an illuminating portrait of a childhood of excitement, adventure, and love” (Kirkus Reviews) this is an extraordinary account of a deep mother-son bond and the joy and toll of growing up in a radical age. Peter Andreas is an insightful and candid narrator of “a profound and enlightening book that will open readers up to different ideas about love, acceptance, and the bond between mother and son” (Library Journal, starred review).

Carol Andreas was a traditional 1950s housewife from a small Mennonite town in central Kansas who became a radical feminist and Marxist revolutionary. From the late sixties to the early eighties, she went through multiple husbands and countless lovers while living in three states and five countries. She took her youngest son, Peter, with her wherever she went, even kidnapping him and running off to South America after his straitlaced father won a long and bitter custody fight.

They were chasing the revolution together, though the more they chased it the more distant it became. They battled the bad “isms” (sexism, imperialism, capitalism, fascism, consumerism), and fought for the good “isms” (feminism, socialism, communism, egalitarianism). Between the ages of five and eleven, Peter lived in more than a dozen homes, moving from the comfortably bland suburbs of Detroit to a hippie commune in Berkeley to a socialist collective farm in pre-military coup Chile to highland villages and coastal shantytowns in Peru. When they secretly returned to America they settled down clandestinely in Denver, where his mother changed her name to hide from his father.

A “luminous memoir” (Publishers Marketplace, starred review) and “an illuminating portrait of a childhood of excitement, adventure, and love” (Kirkus Reviews) this is an extraordinary account of a deep mother-son bond and the joy and toll of growing up in a radical age. Peter Andreas is an insightful and candid narrator of “a profound and enlightening book that will open readers up to different ideas about love, acceptance, and the bond between mother and son” (Library Journal, starred review).

Excerpt

Rebel Mother Carol and Carl

MY MOTHER HAD always been the one to pick me up from nursery school, but one late June afternoon in 1969, a couple of weeks before my fourth birthday, my father arrived first and pushed me into the backseat of his gray Chevy Malibu. I could tell that something was not right by how tightly he gripped my hand and hurried me out of the school building to his car. Standing on my toes on the seat to look out the back window, I saw my mother’s beige VW station wagon arrive behind us just as we started to pull away from the curb.

I waved at her. “Daddy, Daddy, Mommy’s coming!”

“No, Mommy’s leaving,” my father grumbled, turning his head back briefly. “Now please, sit down.” My father slammed the accelerator and the car jerked forward, tipping me off balance.

My mother, seeing that my father had already taken me, tailed us for as long as she could. She projected an air of calm, waving cheerfully at me from over the steering wheel, but she must have been anything but. Eventually, my father accelerated so fast that she became smaller and smaller, then disappeared into the distance. “Mommy’s gone,” I cried out, tears welling in my eyes.

“Yes, that’s right, Peter, Mommy is gone. But don’t worry, I’ll take care of you.”

That afternoon was my first memory. It marked the beginning of my parents’ war over me. Earlier that day, while no one was home, my mother had quickly packed as much as she could into her car, mostly clothes and books but also a few of her favorite Pakistani pictures hanging in the living room, and moved out of the house for good. When my father got home from work and saw the empty closet, the first thing he’d done was rush to my preschool. Over the next six years, I would be kidnapped from school two more times—both times by my mother, who would carry me first across the country and then across continents. My father won that opening battle, but he would lose the war.

During her devoutly conservative childhood, my mother would have seemed like the last person to kidnap her own child. She was born in 1933 in North Newton, a tightly knit Mennonite community of a few thousand inhabitants in central Kansas, where Mennonite wheat farmers from Ukraine had originally settled in the 1870s. When my mother was a child, most people didn’t venture out of North Newton much; if they did, they were usually visiting other Mennonite communities in rural Middle America. As a pacifist Christian sect closely related to the Amish—though unlike the Amish they don’t reject the technologies of modern life—Mennonites mostly intermarried, spent Sundays at church, and kept to themselves.

My mother’s parents, Willis Rich and Hulda Penner, had met while waiting in line their freshman year to enroll in classes at Bethel, the local college where most college-bound Mennonites in the area went to school and where Willis would eventually become director of public relations. Although they were devoutly religious—going to church, praying before meals, singing church hymns, dressing conservatively—they were also less strict than other Mennonite families in North Newton. As the PR man for the college, Willis made sure to bring interesting speakers from all over the world to campus, and Hulda would entertain them at their house a few blocks away. My mother and her three siblings served the guests at the table, which gave her an opportunity to pepper them with questions.

Perhaps it was partly due to such outside influences that, by the time my mother was a teenager, she had become enough of a skeptic to declare herself an agnostic, which I imagine must have rattled the rest of the community. Her parents, though, took it in stride. Mennonites did not dance (“that led to sex”) and did not play cards (“that led to gambling”), but Willis and Hulda let their children do both—as long as it was out of sight, behind closed doors. So when the doorbell rang while the kids were playing cards, they quickly hid them under the table; and they could playfully dance around the house, but any kind of dancing in public, including at the high school dances organized for the non-Mennonites from the other side of town, was not allowed.

The Rich family differed from the rest of the community in other ways, too. They were Democrats in a Republican town. Willis’s sister, Selma, whom my mother looked up to as a role model, was an early civil rights advocate and campaigned to integrate the local swimming pool and movie theater. Also unusual was that Willis had gone to Columbia University for a graduate degree in education, and his first job was as a teacher in the non-Mennonite town of Bentley, Kansas. Although there were plenty of Bibles scattered about the house, Willis spent more time reading Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking—and enthusiastically quoting from it out loud to his kids—than he did Scripture. Willis was always upbeat and optimistic, which remained true even after he became afflicted with multiple sclerosis and was confined to a wheelchair.

During Christmas vacation, 1947, just a little more than a month after my mother turned fourteen, she and a friend had gone out sledding—or tried to, anyway, in the flat Kansas fields. She’d been allowed to exchange her plain skirt for a pair of pants for the sledding, and the curls of her fine, shoulder-length hair poked out of her wool winter cap. It was her smile and her beautiful green eyes that captivated my father, the handsome twenty-year-old Bethel College student who stopped by the side of the road that afternoon and offered to pull her sled behind his shiny black 1931 Ford Model A coupe. My mother asked my father if he played a sport and he replied, with a grin, “I play the radio.” He was not the athletic type, but he did have a car, and it did have a radio.

My father, Carl Roland Andreas, started taking my mother, Carol Ruth Rich, out once a week, holding her hand at the drive-in or at the high school and college basketball games. Except for the nearly seven-year age gap, my father seemed like a perfect suitor—polite, responsible, hardworking, and from a good Mennonite family. His grandfather had even been a Mennonite minister married to the church organist.

Beyond her pretty face, my father was drawn to my mother’s complex combination of innocence and maturity. My mother, in turn, was flattered by the attention of an older man, especially one who had resisted his mother’s pressure to become a minister. And he seemed downright worldly compared to the other Newton boys; he had traveled to Cuba with his college roommate during a winter break, worked on the railroad in Colorado for a year after high school, and spent the last year of World War II as a conscientious objector in a Civilian Public Service camp in Mississippi, building latrines in poor rural communities. My mother admired those who defied the draft and had tasted life outside of Kansas. Her hero growing up was her cousin Dwight (Aunt Selma’s son), who spent six months in county jail for refusing to register for the draft and then lived in India for four years before returning to teach at Bethel.

Two years after they met, my mother and father got engaged and kissed for the first time. A year after that they were married. My mother was seventeen; my father, twenty-four. Mennonite girls in North Newton often married young, but usually not that young, and usually not to someone that much older.

Yet, even as my father’s college buddies teased him for robbing the cradle, most everyone seemed pleased with the match—except for the bride. My mother was already starting to have ideological doubts about traditional marriage as a concept itself. As my mother would later tell it, as she and my father arrived at their late-afternoon marriage ceremony on Bethel’s Goerz House lawn, she turned suddenly and blurted: “You know what? It just occurred to me that I really don’t know if I believe in monogamy.” A bold thing to say in 1950s America, this was downright scandalous in a conservative religious community in central Kansas.

“Tootsie, what difference does it make?” my startled father replied, trying to stay calm. “Look over there. There must be five hundred people waiting for us. They all believe in monogamy. They can’t all be wrong. And besides, you want to live with me, don’t you? How else can we swing that?”

They went through with the ceremony and then moved into an upstairs apartment near campus on South College Avenue. While my father waited for my mother to get through school, he took a job as a bill collector and bookkeeper for the local Mennonite Deaconess Hospital. Whatever my mother’s hesitations, the truth was my father was her ride out of North Newton. Originally from Beatrice, Nebraska, a few hours’ drive away, he had no plans to stay in town after college. He and my mother both wanted to go to graduate school, which meant not only leaving North Newton but probably Kansas as well. Many others from my mother’s generation, including her siblings, would also end up moving away, but she was more eager to grow up and get out to see the world than most. Always disciplined and studious, she skipped a grade at Newton High and rushed through Bethel as fast as she could. “I was only nineteen when I finished college,” my mother always reminded me. “I did it so I could be with your father.”

Carol and Carl Andreas, May 1951

As soon as she had her diploma, she and my father moved to Minneapolis–Saint Paul to attend the University of Minnesota together, where my father earned an MA in hospital administration and my mother an MA in psychology. My mother got him through his course work by helping him write and type up his papers.

My father and mother as a traditional 1950s married couple

Soon they had two little boys, Joel and Ronald, a year and a half apart. My mother loved her children but grew restless under the expectations of a 1950s housewife, a role she’d never intended to play. With my mother’s encouragement, my father signed up for a four-year stint as coordinator of a U.S. government–funded medical school program in Karachi, Pakistan. My father saw it as a good career move, but my mother, now in her mid-twenties, was mainly eager to experience life outside of America—and Pakistan happened to be the post that was open. She miscalculated. Instead of worldly adventure, she found herself in an even more insulated life, cooped up in charge of two rambunctious boys in a stifled and claustrophobic U.S. diplomatic community. My mother did her best to keep busy—she studied Urdu, scoured for antiques in Karachi’s old bazaar, volunteered to teach English to Pakistani women—but was still restless and frustrated.

It didn’t help matters that my father was a workaholic who, according to my mother, was reluctant to take a single day off work, not even a Saturday or Sunday. This was true even before the move to Pakistan; there were no family vacations except for the once- or twice-a-year cross-country drives to visit relatives back in Kansas. In Karachi, my father had little family time beyond an obligatory short daily walk with the kids at dusk—usually taking them to review progress on the city’s brand-new sewage plant—while my mother, dripping sweat, struggled to have dinner on the table when they got home.

My father even resisted the weekend outings she tried to plan: when she insisted on going to the beach, he would reluctantly drive them there but would spend the day sitting in the car. My father could be maddeningly practical: from his perspective, what was the point of sitting on the ground or in a rickety beach chair if the car seat was more shaded and comfortable? He did not share my mother’s interest in foreign cultures or in mingling with the locals; he was just there for the job opportunity, a career stepping-stone, and looked forward to returning to the States. He did everything he could to avoid the spicy cuisine, even if it meant embarrassing my mother by refusing to eat at neighbors’ dinner parties (my father was not a picky eater, but he preferred his food as bland as possible). Even back home he had never liked to eat out, choosing cheap, over-processed chain restaurants whenever possible. As my mother started to experience the world outside of the American Midwest, she came to see my father as frustratingly square and provincial. The only dream that dominated my father’s life was to save a million dollars by the time he retired. She had no dream—not yet—but she had become ashamed of the privileged lives of the diplomatic community and local elites floating in a vast sea of poverty.

My mother also felt restless when she and the kids were cooped up together in the air-conditioned bedrooms during the years before my brothers started school. More than anything, though, she felt isolated. One of her favorite Karachi memories was of a homely camel poking its head affectionately into her car window as she was stopped at an intersection. She would later write, “I had an urge to hug it and kiss it, as if we were two misfits in the world who had finally found each other—a fleeting recognition of my solitude during a time when I didn’t even know enough to keep a diary.”

When the Karachi assignment came to an end in the early sixties, my parents and brothers went right back to the Midwest, this time settling down in Detroit, Michigan. My parents bought a downtown townhouse in Lafayette Park, a middle-class “urban renewal” community. My father had accepted a job offer as business manager for the Wayne State University School of Medicine, and a few years later, he moved on to become a staff member of the United Automobile Workers union, where he would spend the rest of his career, negotiating Social Security and pension benefits.

Intellectually restless and physically exhausted from raising two energetic boys, my mother decided to work on a PhD in sociology at Wayne State, where she read works by Marx, Engels, and other radical theorists for the first time. My father was supportive of my mother getting a PhD as a sensible career move—he liked the idea of two incomes—even though he didn’t really understand why anyone would be interested in sociological theory, and certainly wasn’t prepared for the ways in which her personal beliefs might be affected. In the midst of writing her doctoral dissertation, a critique of U.S. aid to Pakistan as a tool of political and economic domination, she unexpectedly became pregnant—yet another boy. “You were a mistake,” my mother used to say, “but a happy one.” I arrived on July 8, 1965.

One of the black-and-white pictures my mother pasted in my baby album is of our entire family—my mother, father, and two older brothers—gathered together on a lawn, me in the middle propped up on my father’s knee, everyone posing for the camera. My father and mother are both beaming—he at the camera and she at the infant me—proud of the family they created. The caption under the photo, in my mother’s neat, easy-flowing cursive handwriting, reads, “This picture, which was taken on May 30, 1966 (Mother and Daddy’s 15th wedding anniversary), was sent to many family friends and illustrates the joy that reigned in Peter’s family when he was a baby.” I wonder if she knew then how fleeting it would be.

Family photo, May 30, 1966

As happy a surprise as I might have been, I was nonetheless inconvenient. My arrival coincided with my mother’s attempt to move beyond being a housewife, so she and my father hired a nanny, Mrs. Ruffie, to help take care of me during the day. My mother was preoccupied with her new life as a part-time professor (at Wayne State and at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor) and a part-time activist—which to her were the same thing. As the civil rights, women’s rights, and antiwar movements were exploding across the country, with college campuses at the epicenter, my mother saw her job in the classroom as a way to mobilize students to join the cause and clamor for social justice. I went to my first antiwar demonstration before I was eating solid foods. At age three, I rode a “flower power” tricycle sporting a peace sign in a parade.

My mother’s passion for political activism in the mid-sixties found its first outlet in a campaign against the war toys in her sons’ toy box. It was the perfect cause for a mother with pacifist Mennonite roots; G.I. Joe never met a more formidable adversary. In my mother’s view, war toys—an evil marriage of American militarism and consumer capitalism—were part of the Pentagon’s pro-war propaganda machine targeting impressionable children. She fired off letters to all the major toy companies, berating them for contributing to the “war mania” her sons were exposed to. She gave them a long list of toys they could be making instead of plastic guns and soldiers. She pleaded, how about “fire-fighting and forest ranger sets?” She even offered her help: “I promise to work actively to promote the sale of such new toys if you will openly declare a policy of responsible action in eliminating war toys from your inventory.” They replied that their military toys were simply a response to consumer demand; that the toys promoted patriotism and offered a healthy outlet for children’s hostilities.

My mother proudly called me the “flower-power trike rider”

My mother was undeterred. She wrote letters to the newspapers and organized petitions, going door-to-door in our neighborhood, collecting hundreds of signatures to pressure area stores to stop carrying war toys. A local drugstore and a supermarket reluctantly agreed to replace their war toys on display with shovels, buckets, garden tools, and other toy kits and games. My mother’s crusade was written up in a front-page story in the Detroit Free Press, with the headline “One Mother Opens Fire on War Toys for Kids.” Meanwhile, my older brothers, tired of simple toys like the wooden building blocks our father had made for them, sneaked away to play with toy soldiers at their friends’ houses.

But by the end of the decade, though she’d lost none of her strident moral righteousness, my mother stopped preaching pacifism and began embracing the anger that she felt was essential for radical change. As was true for so many activists at the time, the escalating war in Vietnam became the turning point in my mother’s sympathies. She and my pacifist father both marched against Washington’s military involvement in Vietnam, but unlike my father, my mother began to root for the other side—Ho Chi Minh and the Vietcong, whom she viewed as heroic anti-imperialists defiantly fending off foreign military aggression. As she came to see it, how could anyone expect them to defend themselves by simply sitting on their hands? Privileged Western observers far from the villages being carpet bombed by U.S. warplanes, she argued, were in no position to tell the North Vietnamese to simply lay down their arms. But as my father insistently kept trying to remind my mother, their Mennonite upbringing told them to be against all wars, all violence, and not take sides. A rift was growing between my parents.

Another fault line in their marriage was the idea of monogamy, which my mother came to see as a source of male oppression that perpetuated a patriarchal society. When my mother confessed to my father that she’d had a fling with a man from California named Burt while attending a War Resisters League meeting in Golden, Colorado, he angrily demanded Burt’s California address. Over the next several months, he kept sending Burt letters demanding not only that he apologize to our family, but that he cease having affairs with anyone:

I am increasingly disturbed by the realization that you were able to behave in such an irresponsible fashion with my wife last September in Golden, Colorado. You were aware of the fact that she was a married woman with three fine boys, and I believe that you owe her family an apology. It will make it possible for me to establish a finer relationship with Carol if I know that you will be more careful in the future of such involvements with others.

When my father didn’t get a reply, he sent another letter: “Please refer to my letter to you regarding your relations with my wife in Golden, Colorado, last September. You may not appreciate the great anxiety you have created in this family. Carol comes from a very fine home with high moral standards. I likewise come from a fine and stable home where the kind of behavior you exhibit is unheard of.” He concluded, “I expect to hear from you soon.”

The reply my father eventually received was not what he had asked for:

Dear Mr. Andreas,

Yes, I was aware of the fact that Carol was a married woman with children, and I can understand and maybe even feel some of the anxiety that our relationship created there. But Carol is also an adult human being, capable of approaching the world as an individual and of evoking a response as an individual.

I cannot make a Satan out of myself for you. That would be both dishonest to myself and terribly insulting to Carol. I don’t use people lightly. And while my morality is different than yours it is a morality, and quite a strict one. It is based on a response to the individual in the situation and on their worth as autonomous human beings, rather than on static rules.

Finally, I can’t make any promises about my future involvement with others. This is so, first, because, as I said, I don’t approach people with a set of static rules. More importantly, though, I can’t make any such promise because the request for it doesn’t make any sense. When you ask that, you are saying that the relationship between A and B (you and Carol) is dependent on C’s (Burt’s) pledge of future conduct with D, E, and F (unknown, unmet other). The relationship between you and Carol depends only on you and Carol. The attempt to create a Satan to serve as a parking place for your unresolved questions is doomed to failure.

You and your family have my sincere best wishes for the new year.

Burt’s response left my father feeling even more indignant. His hardwired 1950s sensibilities were banging up against the loosening morals of the 1960s. Peace never really returned to the family after that affair. From then on, my parents argued in their bedroom late at night in angry, hushed voices. My mother arranged for them to see a marriage counselor, but after going once my father refused to go again.

Meanwhile, my mother had become a full-blown political activist in a city consumed by activism. Detroit was in flames. The July 1967 riots left fires burning around Lafayette Park, where we lived, and the governor sent in National Guard troop carriers to major intersections nearby. President Johnson deployed army troops. Forty-three people died, over one thousand were injured, more than seven thousand arrested, and over two thousand buildings destroyed. Yet, in the midst of this chaos, my mother cheerfully sent a letter to family and friends, urging them to visit: “This year there should be an added incentive to visit the city that leads the nation in promoting rebellion among its alienated minorities.”

To show her solidarity and join the cause, she became a member of People Against Racism, which worked in tandem with the Black Panthers and the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement. As a coordinator of the Detroit Committee to End the War Now, she helped organize massive antiwar demonstrations and started hanging out with Maoists, Trotskyists, members of the Communist Party USA, and black nationalists of the Republic of New Africa. My mother became a spokesperson for the Union of Radical Sociologists at American Sociological Association meetings, and was a founder of the journal The Insurgent Sociologist, meant to provide a voice and publishing outlet for left-wing activist sociologists.

My mother also led the way in uniting disparate feminist groups in the Michigan Women’s Liberation Coalition. Male reporters were banned from the press conference announcing the coalition, which itself became the lead story in the press coverage. “Feminist Groups Oust Newsmen; Form Council” ran the headline in the Detroit Free Press; “Feminist Meeting Clears Out Men” reported the Detroit News. It was a calculated move; my mother told the Free Press, “We felt we had to make this point to them, that part of the oppression of women stems from the fact that the media is largely controlled by men.” The Detroit News quoted her as saying that the ban would continue “until we’re satisfied enough women have been hired in radio and television.” Male camera operators, however, were allowed into the press conference “just this one time,” she said. Of course, they had to let them in: otherwise, with no women camera operators present, there would be no media coverage of the press conference.

In the wake of all of this, the classroom was simply another opportunity for my mother to engage in political organizing and her vague but lofty-sounding “consciousness raising.” She taught a course at the University of Michigan on the Sociology of Sex, and it inspired her to write a book, Sex and Caste in America. The book was a manifesto of sorts for women’s liberation, in which she declared that the nuclear family should be abolished: “The family maintains the economic structures that thrive on sexism (as well as on racism and imperialism).” I was much too young to understand at the time, but I can only imagine how my father, the straitlaced, traditional American family man, felt about her declaration.

During this time, my mother’s appearance changed radically along with her politics. She disposed of the heels, mascara, and hair spray that had defined her look as a 1950s housewife, and later, as a prim and proper young professional. She stopped putting her hair up or curling it, and instead let it hang straight down. Razors were out, unshaved legs and armpits were in. Pants replaced dresses. She tossed out all her bras, and would not put one on again for years. She avoided curling irons and makeup for the rest of her life. Her favorite pair of shoes, brown leather Pakistani sandals with thin straps, soon were pretty much all that remained from her old shoe collection. Cool and casual replaced proper and conventional. There was only one thing left for my mother to do to complete her transformation and leave the last remnants of her housewife identity behind.

My mother and father in June 1969, the month they separated

MY MOTHER HAD always been the one to pick me up from nursery school, but one late June afternoon in 1969, a couple of weeks before my fourth birthday, my father arrived first and pushed me into the backseat of his gray Chevy Malibu. I could tell that something was not right by how tightly he gripped my hand and hurried me out of the school building to his car. Standing on my toes on the seat to look out the back window, I saw my mother’s beige VW station wagon arrive behind us just as we started to pull away from the curb.

I waved at her. “Daddy, Daddy, Mommy’s coming!”

“No, Mommy’s leaving,” my father grumbled, turning his head back briefly. “Now please, sit down.” My father slammed the accelerator and the car jerked forward, tipping me off balance.

My mother, seeing that my father had already taken me, tailed us for as long as she could. She projected an air of calm, waving cheerfully at me from over the steering wheel, but she must have been anything but. Eventually, my father accelerated so fast that she became smaller and smaller, then disappeared into the distance. “Mommy’s gone,” I cried out, tears welling in my eyes.

“Yes, that’s right, Peter, Mommy is gone. But don’t worry, I’ll take care of you.”

That afternoon was my first memory. It marked the beginning of my parents’ war over me. Earlier that day, while no one was home, my mother had quickly packed as much as she could into her car, mostly clothes and books but also a few of her favorite Pakistani pictures hanging in the living room, and moved out of the house for good. When my father got home from work and saw the empty closet, the first thing he’d done was rush to my preschool. Over the next six years, I would be kidnapped from school two more times—both times by my mother, who would carry me first across the country and then across continents. My father won that opening battle, but he would lose the war.

During her devoutly conservative childhood, my mother would have seemed like the last person to kidnap her own child. She was born in 1933 in North Newton, a tightly knit Mennonite community of a few thousand inhabitants in central Kansas, where Mennonite wheat farmers from Ukraine had originally settled in the 1870s. When my mother was a child, most people didn’t venture out of North Newton much; if they did, they were usually visiting other Mennonite communities in rural Middle America. As a pacifist Christian sect closely related to the Amish—though unlike the Amish they don’t reject the technologies of modern life—Mennonites mostly intermarried, spent Sundays at church, and kept to themselves.

My mother’s parents, Willis Rich and Hulda Penner, had met while waiting in line their freshman year to enroll in classes at Bethel, the local college where most college-bound Mennonites in the area went to school and where Willis would eventually become director of public relations. Although they were devoutly religious—going to church, praying before meals, singing church hymns, dressing conservatively—they were also less strict than other Mennonite families in North Newton. As the PR man for the college, Willis made sure to bring interesting speakers from all over the world to campus, and Hulda would entertain them at their house a few blocks away. My mother and her three siblings served the guests at the table, which gave her an opportunity to pepper them with questions.

Perhaps it was partly due to such outside influences that, by the time my mother was a teenager, she had become enough of a skeptic to declare herself an agnostic, which I imagine must have rattled the rest of the community. Her parents, though, took it in stride. Mennonites did not dance (“that led to sex”) and did not play cards (“that led to gambling”), but Willis and Hulda let their children do both—as long as it was out of sight, behind closed doors. So when the doorbell rang while the kids were playing cards, they quickly hid them under the table; and they could playfully dance around the house, but any kind of dancing in public, including at the high school dances organized for the non-Mennonites from the other side of town, was not allowed.

The Rich family differed from the rest of the community in other ways, too. They were Democrats in a Republican town. Willis’s sister, Selma, whom my mother looked up to as a role model, was an early civil rights advocate and campaigned to integrate the local swimming pool and movie theater. Also unusual was that Willis had gone to Columbia University for a graduate degree in education, and his first job was as a teacher in the non-Mennonite town of Bentley, Kansas. Although there were plenty of Bibles scattered about the house, Willis spent more time reading Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking—and enthusiastically quoting from it out loud to his kids—than he did Scripture. Willis was always upbeat and optimistic, which remained true even after he became afflicted with multiple sclerosis and was confined to a wheelchair.

During Christmas vacation, 1947, just a little more than a month after my mother turned fourteen, she and a friend had gone out sledding—or tried to, anyway, in the flat Kansas fields. She’d been allowed to exchange her plain skirt for a pair of pants for the sledding, and the curls of her fine, shoulder-length hair poked out of her wool winter cap. It was her smile and her beautiful green eyes that captivated my father, the handsome twenty-year-old Bethel College student who stopped by the side of the road that afternoon and offered to pull her sled behind his shiny black 1931 Ford Model A coupe. My mother asked my father if he played a sport and he replied, with a grin, “I play the radio.” He was not the athletic type, but he did have a car, and it did have a radio.

My father, Carl Roland Andreas, started taking my mother, Carol Ruth Rich, out once a week, holding her hand at the drive-in or at the high school and college basketball games. Except for the nearly seven-year age gap, my father seemed like a perfect suitor—polite, responsible, hardworking, and from a good Mennonite family. His grandfather had even been a Mennonite minister married to the church organist.

Beyond her pretty face, my father was drawn to my mother’s complex combination of innocence and maturity. My mother, in turn, was flattered by the attention of an older man, especially one who had resisted his mother’s pressure to become a minister. And he seemed downright worldly compared to the other Newton boys; he had traveled to Cuba with his college roommate during a winter break, worked on the railroad in Colorado for a year after high school, and spent the last year of World War II as a conscientious objector in a Civilian Public Service camp in Mississippi, building latrines in poor rural communities. My mother admired those who defied the draft and had tasted life outside of Kansas. Her hero growing up was her cousin Dwight (Aunt Selma’s son), who spent six months in county jail for refusing to register for the draft and then lived in India for four years before returning to teach at Bethel.

Two years after they met, my mother and father got engaged and kissed for the first time. A year after that they were married. My mother was seventeen; my father, twenty-four. Mennonite girls in North Newton often married young, but usually not that young, and usually not to someone that much older.

Yet, even as my father’s college buddies teased him for robbing the cradle, most everyone seemed pleased with the match—except for the bride. My mother was already starting to have ideological doubts about traditional marriage as a concept itself. As my mother would later tell it, as she and my father arrived at their late-afternoon marriage ceremony on Bethel’s Goerz House lawn, she turned suddenly and blurted: “You know what? It just occurred to me that I really don’t know if I believe in monogamy.” A bold thing to say in 1950s America, this was downright scandalous in a conservative religious community in central Kansas.

“Tootsie, what difference does it make?” my startled father replied, trying to stay calm. “Look over there. There must be five hundred people waiting for us. They all believe in monogamy. They can’t all be wrong. And besides, you want to live with me, don’t you? How else can we swing that?”

They went through with the ceremony and then moved into an upstairs apartment near campus on South College Avenue. While my father waited for my mother to get through school, he took a job as a bill collector and bookkeeper for the local Mennonite Deaconess Hospital. Whatever my mother’s hesitations, the truth was my father was her ride out of North Newton. Originally from Beatrice, Nebraska, a few hours’ drive away, he had no plans to stay in town after college. He and my mother both wanted to go to graduate school, which meant not only leaving North Newton but probably Kansas as well. Many others from my mother’s generation, including her siblings, would also end up moving away, but she was more eager to grow up and get out to see the world than most. Always disciplined and studious, she skipped a grade at Newton High and rushed through Bethel as fast as she could. “I was only nineteen when I finished college,” my mother always reminded me. “I did it so I could be with your father.”

Carol and Carl Andreas, May 1951

As soon as she had her diploma, she and my father moved to Minneapolis–Saint Paul to attend the University of Minnesota together, where my father earned an MA in hospital administration and my mother an MA in psychology. My mother got him through his course work by helping him write and type up his papers.

My father and mother as a traditional 1950s married couple

Soon they had two little boys, Joel and Ronald, a year and a half apart. My mother loved her children but grew restless under the expectations of a 1950s housewife, a role she’d never intended to play. With my mother’s encouragement, my father signed up for a four-year stint as coordinator of a U.S. government–funded medical school program in Karachi, Pakistan. My father saw it as a good career move, but my mother, now in her mid-twenties, was mainly eager to experience life outside of America—and Pakistan happened to be the post that was open. She miscalculated. Instead of worldly adventure, she found herself in an even more insulated life, cooped up in charge of two rambunctious boys in a stifled and claustrophobic U.S. diplomatic community. My mother did her best to keep busy—she studied Urdu, scoured for antiques in Karachi’s old bazaar, volunteered to teach English to Pakistani women—but was still restless and frustrated.

It didn’t help matters that my father was a workaholic who, according to my mother, was reluctant to take a single day off work, not even a Saturday or Sunday. This was true even before the move to Pakistan; there were no family vacations except for the once- or twice-a-year cross-country drives to visit relatives back in Kansas. In Karachi, my father had little family time beyond an obligatory short daily walk with the kids at dusk—usually taking them to review progress on the city’s brand-new sewage plant—while my mother, dripping sweat, struggled to have dinner on the table when they got home.

My father even resisted the weekend outings she tried to plan: when she insisted on going to the beach, he would reluctantly drive them there but would spend the day sitting in the car. My father could be maddeningly practical: from his perspective, what was the point of sitting on the ground or in a rickety beach chair if the car seat was more shaded and comfortable? He did not share my mother’s interest in foreign cultures or in mingling with the locals; he was just there for the job opportunity, a career stepping-stone, and looked forward to returning to the States. He did everything he could to avoid the spicy cuisine, even if it meant embarrassing my mother by refusing to eat at neighbors’ dinner parties (my father was not a picky eater, but he preferred his food as bland as possible). Even back home he had never liked to eat out, choosing cheap, over-processed chain restaurants whenever possible. As my mother started to experience the world outside of the American Midwest, she came to see my father as frustratingly square and provincial. The only dream that dominated my father’s life was to save a million dollars by the time he retired. She had no dream—not yet—but she had become ashamed of the privileged lives of the diplomatic community and local elites floating in a vast sea of poverty.

My mother also felt restless when she and the kids were cooped up together in the air-conditioned bedrooms during the years before my brothers started school. More than anything, though, she felt isolated. One of her favorite Karachi memories was of a homely camel poking its head affectionately into her car window as she was stopped at an intersection. She would later write, “I had an urge to hug it and kiss it, as if we were two misfits in the world who had finally found each other—a fleeting recognition of my solitude during a time when I didn’t even know enough to keep a diary.”

When the Karachi assignment came to an end in the early sixties, my parents and brothers went right back to the Midwest, this time settling down in Detroit, Michigan. My parents bought a downtown townhouse in Lafayette Park, a middle-class “urban renewal” community. My father had accepted a job offer as business manager for the Wayne State University School of Medicine, and a few years later, he moved on to become a staff member of the United Automobile Workers union, where he would spend the rest of his career, negotiating Social Security and pension benefits.

Intellectually restless and physically exhausted from raising two energetic boys, my mother decided to work on a PhD in sociology at Wayne State, where she read works by Marx, Engels, and other radical theorists for the first time. My father was supportive of my mother getting a PhD as a sensible career move—he liked the idea of two incomes—even though he didn’t really understand why anyone would be interested in sociological theory, and certainly wasn’t prepared for the ways in which her personal beliefs might be affected. In the midst of writing her doctoral dissertation, a critique of U.S. aid to Pakistan as a tool of political and economic domination, she unexpectedly became pregnant—yet another boy. “You were a mistake,” my mother used to say, “but a happy one.” I arrived on July 8, 1965.

One of the black-and-white pictures my mother pasted in my baby album is of our entire family—my mother, father, and two older brothers—gathered together on a lawn, me in the middle propped up on my father’s knee, everyone posing for the camera. My father and mother are both beaming—he at the camera and she at the infant me—proud of the family they created. The caption under the photo, in my mother’s neat, easy-flowing cursive handwriting, reads, “This picture, which was taken on May 30, 1966 (Mother and Daddy’s 15th wedding anniversary), was sent to many family friends and illustrates the joy that reigned in Peter’s family when he was a baby.” I wonder if she knew then how fleeting it would be.

Family photo, May 30, 1966

As happy a surprise as I might have been, I was nonetheless inconvenient. My arrival coincided with my mother’s attempt to move beyond being a housewife, so she and my father hired a nanny, Mrs. Ruffie, to help take care of me during the day. My mother was preoccupied with her new life as a part-time professor (at Wayne State and at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor) and a part-time activist—which to her were the same thing. As the civil rights, women’s rights, and antiwar movements were exploding across the country, with college campuses at the epicenter, my mother saw her job in the classroom as a way to mobilize students to join the cause and clamor for social justice. I went to my first antiwar demonstration before I was eating solid foods. At age three, I rode a “flower power” tricycle sporting a peace sign in a parade.

My mother’s passion for political activism in the mid-sixties found its first outlet in a campaign against the war toys in her sons’ toy box. It was the perfect cause for a mother with pacifist Mennonite roots; G.I. Joe never met a more formidable adversary. In my mother’s view, war toys—an evil marriage of American militarism and consumer capitalism—were part of the Pentagon’s pro-war propaganda machine targeting impressionable children. She fired off letters to all the major toy companies, berating them for contributing to the “war mania” her sons were exposed to. She gave them a long list of toys they could be making instead of plastic guns and soldiers. She pleaded, how about “fire-fighting and forest ranger sets?” She even offered her help: “I promise to work actively to promote the sale of such new toys if you will openly declare a policy of responsible action in eliminating war toys from your inventory.” They replied that their military toys were simply a response to consumer demand; that the toys promoted patriotism and offered a healthy outlet for children’s hostilities.

My mother proudly called me the “flower-power trike rider”

My mother was undeterred. She wrote letters to the newspapers and organized petitions, going door-to-door in our neighborhood, collecting hundreds of signatures to pressure area stores to stop carrying war toys. A local drugstore and a supermarket reluctantly agreed to replace their war toys on display with shovels, buckets, garden tools, and other toy kits and games. My mother’s crusade was written up in a front-page story in the Detroit Free Press, with the headline “One Mother Opens Fire on War Toys for Kids.” Meanwhile, my older brothers, tired of simple toys like the wooden building blocks our father had made for them, sneaked away to play with toy soldiers at their friends’ houses.

But by the end of the decade, though she’d lost none of her strident moral righteousness, my mother stopped preaching pacifism and began embracing the anger that she felt was essential for radical change. As was true for so many activists at the time, the escalating war in Vietnam became the turning point in my mother’s sympathies. She and my pacifist father both marched against Washington’s military involvement in Vietnam, but unlike my father, my mother began to root for the other side—Ho Chi Minh and the Vietcong, whom she viewed as heroic anti-imperialists defiantly fending off foreign military aggression. As she came to see it, how could anyone expect them to defend themselves by simply sitting on their hands? Privileged Western observers far from the villages being carpet bombed by U.S. warplanes, she argued, were in no position to tell the North Vietnamese to simply lay down their arms. But as my father insistently kept trying to remind my mother, their Mennonite upbringing told them to be against all wars, all violence, and not take sides. A rift was growing between my parents.

Another fault line in their marriage was the idea of monogamy, which my mother came to see as a source of male oppression that perpetuated a patriarchal society. When my mother confessed to my father that she’d had a fling with a man from California named Burt while attending a War Resisters League meeting in Golden, Colorado, he angrily demanded Burt’s California address. Over the next several months, he kept sending Burt letters demanding not only that he apologize to our family, but that he cease having affairs with anyone:

I am increasingly disturbed by the realization that you were able to behave in such an irresponsible fashion with my wife last September in Golden, Colorado. You were aware of the fact that she was a married woman with three fine boys, and I believe that you owe her family an apology. It will make it possible for me to establish a finer relationship with Carol if I know that you will be more careful in the future of such involvements with others.

When my father didn’t get a reply, he sent another letter: “Please refer to my letter to you regarding your relations with my wife in Golden, Colorado, last September. You may not appreciate the great anxiety you have created in this family. Carol comes from a very fine home with high moral standards. I likewise come from a fine and stable home where the kind of behavior you exhibit is unheard of.” He concluded, “I expect to hear from you soon.”

The reply my father eventually received was not what he had asked for:

Dear Mr. Andreas,

Yes, I was aware of the fact that Carol was a married woman with children, and I can understand and maybe even feel some of the anxiety that our relationship created there. But Carol is also an adult human being, capable of approaching the world as an individual and of evoking a response as an individual.

I cannot make a Satan out of myself for you. That would be both dishonest to myself and terribly insulting to Carol. I don’t use people lightly. And while my morality is different than yours it is a morality, and quite a strict one. It is based on a response to the individual in the situation and on their worth as autonomous human beings, rather than on static rules.

Finally, I can’t make any promises about my future involvement with others. This is so, first, because, as I said, I don’t approach people with a set of static rules. More importantly, though, I can’t make any such promise because the request for it doesn’t make any sense. When you ask that, you are saying that the relationship between A and B (you and Carol) is dependent on C’s (Burt’s) pledge of future conduct with D, E, and F (unknown, unmet other). The relationship between you and Carol depends only on you and Carol. The attempt to create a Satan to serve as a parking place for your unresolved questions is doomed to failure.

You and your family have my sincere best wishes for the new year.

Burt’s response left my father feeling even more indignant. His hardwired 1950s sensibilities were banging up against the loosening morals of the 1960s. Peace never really returned to the family after that affair. From then on, my parents argued in their bedroom late at night in angry, hushed voices. My mother arranged for them to see a marriage counselor, but after going once my father refused to go again.

Meanwhile, my mother had become a full-blown political activist in a city consumed by activism. Detroit was in flames. The July 1967 riots left fires burning around Lafayette Park, where we lived, and the governor sent in National Guard troop carriers to major intersections nearby. President Johnson deployed army troops. Forty-three people died, over one thousand were injured, more than seven thousand arrested, and over two thousand buildings destroyed. Yet, in the midst of this chaos, my mother cheerfully sent a letter to family and friends, urging them to visit: “This year there should be an added incentive to visit the city that leads the nation in promoting rebellion among its alienated minorities.”

To show her solidarity and join the cause, she became a member of People Against Racism, which worked in tandem with the Black Panthers and the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement. As a coordinator of the Detroit Committee to End the War Now, she helped organize massive antiwar demonstrations and started hanging out with Maoists, Trotskyists, members of the Communist Party USA, and black nationalists of the Republic of New Africa. My mother became a spokesperson for the Union of Radical Sociologists at American Sociological Association meetings, and was a founder of the journal The Insurgent Sociologist, meant to provide a voice and publishing outlet for left-wing activist sociologists.

My mother also led the way in uniting disparate feminist groups in the Michigan Women’s Liberation Coalition. Male reporters were banned from the press conference announcing the coalition, which itself became the lead story in the press coverage. “Feminist Groups Oust Newsmen; Form Council” ran the headline in the Detroit Free Press; “Feminist Meeting Clears Out Men” reported the Detroit News. It was a calculated move; my mother told the Free Press, “We felt we had to make this point to them, that part of the oppression of women stems from the fact that the media is largely controlled by men.” The Detroit News quoted her as saying that the ban would continue “until we’re satisfied enough women have been hired in radio and television.” Male camera operators, however, were allowed into the press conference “just this one time,” she said. Of course, they had to let them in: otherwise, with no women camera operators present, there would be no media coverage of the press conference.

In the wake of all of this, the classroom was simply another opportunity for my mother to engage in political organizing and her vague but lofty-sounding “consciousness raising.” She taught a course at the University of Michigan on the Sociology of Sex, and it inspired her to write a book, Sex and Caste in America. The book was a manifesto of sorts for women’s liberation, in which she declared that the nuclear family should be abolished: “The family maintains the economic structures that thrive on sexism (as well as on racism and imperialism).” I was much too young to understand at the time, but I can only imagine how my father, the straitlaced, traditional American family man, felt about her declaration.

During this time, my mother’s appearance changed radically along with her politics. She disposed of the heels, mascara, and hair spray that had defined her look as a 1950s housewife, and later, as a prim and proper young professional. She stopped putting her hair up or curling it, and instead let it hang straight down. Razors were out, unshaved legs and armpits were in. Pants replaced dresses. She tossed out all her bras, and would not put one on again for years. She avoided curling irons and makeup for the rest of her life. Her favorite pair of shoes, brown leather Pakistani sandals with thin straps, soon were pretty much all that remained from her old shoe collection. Cool and casual replaced proper and conventional. There was only one thing left for my mother to do to complete her transformation and leave the last remnants of her housewife identity behind.

My mother and father in June 1969, the month they separated

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (April 17, 2018)

- Length: 336 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501124426

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Rebel Mother Trade Paperback 9781501124426

- Author Photo (jpg): Peter Andreas Photograph by Rythum Vinoben(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit