Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

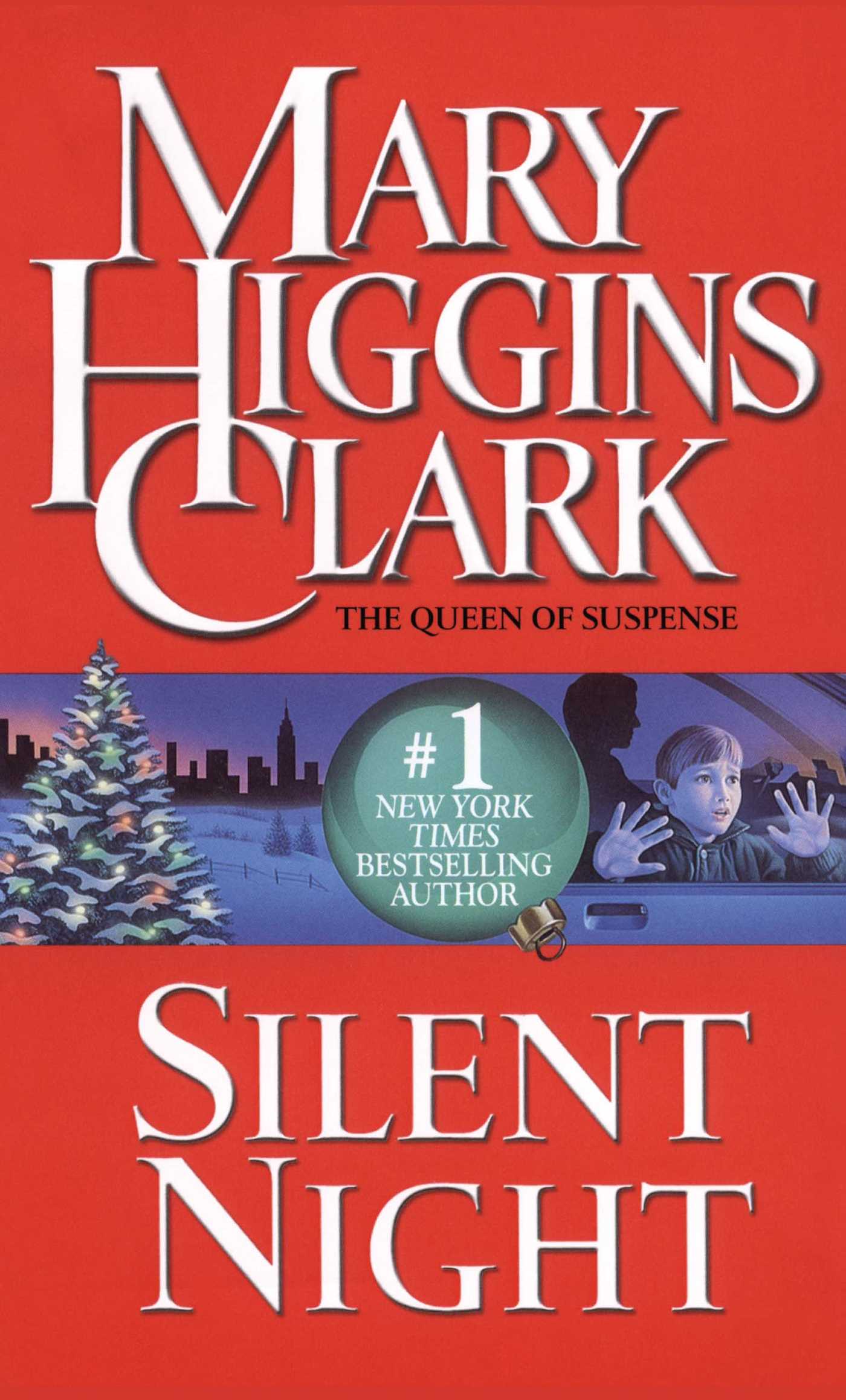

Mary Higgins Clark, the "Queen of Suspense," has crafted a very special holiday story about a child's courage in the face of danger, and the power of love. Charged with menace and thrilling suspense, it is the #1 New York Times bestselling author's gift to readers for all seasons.

When Catherine Dornan's husband, Tom, is diagnosed with leukemia, she and their two young sons travel with him to New York during the holiday season for a lifesaving operation. On Christmas Eve, hoping to lift the boys' spirits, Catherine takes them to see Rockefeller Center's famous Christmas tree; while there, seven-year-old Brian notices a woman taking his mother's wallet. A St. Christopher medal tucked inside the wallet saved his grandfather's life in World War II, and Brian believes with all his heart that it will protect his father now. Impulsively, Brian follows the thief into the subway, and the most dangerous adventure of his young life begins...

When Catherine Dornan's husband, Tom, is diagnosed with leukemia, she and their two young sons travel with him to New York during the holiday season for a lifesaving operation. On Christmas Eve, hoping to lift the boys' spirits, Catherine takes them to see Rockefeller Center's famous Christmas tree; while there, seven-year-old Brian notices a woman taking his mother's wallet. A St. Christopher medal tucked inside the wallet saved his grandfather's life in World War II, and Brian believes with all his heart that it will protect his father now. Impulsively, Brian follows the thief into the subway, and the most dangerous adventure of his young life begins...

Excerpt

Silent Night 1

It was Christmas Eve in New York City. The cab slowly made its way down Fifth Avenue. It was nearly five o’clock. The traffic was heavy and the sidewalks were jammed with last-minute Christmas shoppers, homebound office workers, and tourists anxious to glimpse the elaborately trimmed store windows and the fabled Rockefeller Center Christmas tree.

It was already dark, and the sky was becoming heavy with clouds, an apparent confirmation of the forecast for a white Christmas. But the blinking lights, the sounds of carols, the ringing bells of sidewalk Santas, and the generally jolly mood of the crowd gave an appropriately festive Christmas Eve atmosphere to the famous thoroughfare.

Catherine Dornan sat bolt upright in the back of the cab, her arms around the shoulders of her two small sons. By the rigidity she felt in their bodies, she knew her mother had been right. Ten-year-old Michael’s surliness and seven-year-old Brian’s silence were sure signs that both boys were intensely worried about their dad.

Earlier that afternoon when she had called her mother from the hospital, still sobbing despite the fact that Spence Crowley, her husband’s old friend and doctor, assured her that Tom had come through the operation better than expected, and even suggested that the boys visit him at seven o’clock that night, her mother had spoken to her firmly: “Catherine, you’ve got to pull yourself together,” she had said. “The boys are so upset, and you’re not helping. I think it would be a good idea if you tried to divert them for a little while. Take them down to Rockefeller Center to see the tree, then out to dinner. Seeing you so worried has practically convinced them that Tom will die.”

This isn’t supposed to be happening, Catherine thought. With every fiber of her being she wanted to undo the last ten days, starting with that terrible moment when the phone rang and the call came from St. Mary’s Hospital. “Catherine, can you come right over? Tom collapsed while he was making his rounds.”

Her immediate impression had been that there had to be a mistake. Lean, athletic, thirty-eight-year-old men don’t collapse. And Tom always joked that pediatricians had birthright immunization to all the viruses and germs that arrived with their patients.

But Tom didn’t have immunization from the leukemia that necessitated immediate removal of his grossly enlarged spleen. At the hospital they told her that he must have been ignoring warning signs for months. And I was too stupid to notice, Catherine thought as she tried to keep her lip from quivering.

She glanced out the window and saw that they were passing the Plaza Hotel. Eleven years ago, on her twenty-third birthday, they’d had their wedding reception at the Plaza. Brides are supposed to be nervous, she thought. I wasn’t. I practically ran up the aisle.

Ten days later they’d celebrated little Christmas in Omaha, where Tom had accepted an appointment in the prestigious pediatrics unit of the hospital. We bought that crazy artificial tree in the clearance sale, she thought, remembering how Tom had held it up and said, “Attention Kmart shoppers . . .”

This year, the tree they’d selected so carefully was still in the garage, its branches roped together. They’d decided to come to New York for the surgery. Tom’s best friend, Spence Crowley, was now a prominent surgeon at Sloan-Kettering.

Catherine winced at the thought of how upset she’d been when she was finally allowed to see Tom.

The cab pulled over to the curb. “Okay, here, lady?”

“Yes, fine,” Catherine said, forcing herself to sound cheerful as she pulled out her wallet. “Dad and I brought you guys down here on Christmas Eve five years ago. Brian, I know you were too small, but Michael, do you remember?”

“Yes,” Michael said shortly as he tugged at the handle on the door. He watched as Catherine peeled a five from the wad of bills in her wallet. “How come you have so much money, Mom?”

“When Dad was admitted to the hospital yesterday, they made me take everything he had in his billfold except a few dollars. I should have sorted it out when I got back to Gran’s.”

She followed Michael out onto the sidewalk and held the door open for Brian. They were in front of Saks, near the corner of Forty-ninth Street and Fifth Avenue. Orderly lines of spectators were patiently waiting to get a closeup look at the Christmas window display. Catherine steered her sons to the back of the line. “Let’s see the windows, then we’ll go across the street and get a better look at the tree.”

Brian sighed heavily. This was some Christmas! He hated standing in line—for anything. He decided to play the game he always played when he wanted time to pass quickly. He would pretend he was already where he wanted to be, and tonight that was in his dad’s room in the hospital. He could hardly wait to see his dad, to give him the present his grandmother had said would make him get well.

Brian was so intent on getting on with the evening that when it was finally their turn to get up close to the windows, he moved quickly, barely noticing the scenes of whirling snowflakes and dolls and elves and animals dancing and singing. He was glad when they finally were off the line.

Then, as they started to make their way to the corner to cross the avenue, he saw that a guy with a violin was about to start playing and people were gathering around him. The air suddenly was filled with the sound of “Silent Night,” and people began singing.

Catherine turned back from the curb. “Wait, let’s listen for a few minutes,” she said to the boys.

Brian could hear the catch in her throat and knew that she was trying not to cry. He’d hardly ever seen Mom cry until that morning last week when someone phoned from the hospital and said Dad was real sick.

* * *

Cally walked slowly down Fifth Avenue. It was a little after five, and she was surrounded by crowds of last-minute shoppers, their arms filled with packages. There was a time when she might have shared their excitement, but today all she felt was achingly tired. Work had been so difficult. During the Christmas holidays people wanted to be home, so most of the patients in the hospital had been either depressed or difficult. Their bleak expressions reminded her vividly of her own depression over the last two Christmases, both of them spent in the Bedford correctional facility for women.

She passed St. Patrick’s Cathedral, hesitating only a moment as a memory came back to her of her grandmother taking her and her brother Jimmy there to see the crèche. But that was twenty years ago; she had been ten, and he was six. She wished fleetingly she could go back to that time, change things, keep the bad things from happening, keep Jimmy from becoming what he was now.

Even to think his name was enough to send waves of fear coursing through her body. Dear God, make him leave me alone, she prayed. Early this morning, with Gigi clinging to her, she had answered the angry pounding on her door to find Detective Shore and another officer who said he was Detective Levy standing in the dingy hallway of her apartment building on East Tenth Street and Avenue B.

“Cally, you putting up your brother again?” Shore’s eyes had searched the room behind her for signs of his presence.

The question was Cally’s first indication that Jimmy had managed to escape from Riker’s Island prison.

“The charge is attempted murder of a prison guard,” the detective told her, bitterness filling his voice. “The guard is in critical condition. Your brother shot him and took his uniform. This time you’ll spend a lot more than fifteen months in prison if you help Jimmy to escape. Accessory after the fact the second time around, when you’re talking attempted murder—or murder—of a law officer. Cally, they’ll throw the book at you.”

“I’ve never forgiven myself for giving Jimmy money last time,” Cally had said quietly.

“Sure. And the keys to your car,” he reminded her. “Cally, I warn you. Don’t help him this time.”

“I won’t. You can be sure of that. And I did not know what he had done before.” She’d watched as their eyes again shifted past her. “Go ahead,” she had cried. “Look around. He isn’t here. And if you want to put a tap on my phone, do that, too. I want you to hear me tell Jimmy to turn himself in. Because that’s all I’d have to say to him.”

But surely Jimmy won’t find me, she prayed as she threaded her way through the crowd of shoppers and sightseers. Not this time. After she had served her prison sentence, she took Gigi from the foster home. The social worker had located the tiny apartment on East Tenth Street and gotten her the job as a nurse’s aide at St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital.

This would be her first Christmas with Gigi in two years! If only she had been able to afford a few decent presents for her, she thought. A four-year-old kid should have her own new doll’s carriage, not the battered hand-me-down Cally’d been forced to get for her. The coverlet and pillow she had bought wouldn’t hide the shabbiness of the carriage. But maybe she could find the guy who was selling dolls on the street around here last week. They were only eight dollars, and she remembered that there was even one that looked like Gigi.

She hadn’t had enough money with her that day, but the guy said he’d be on Fifth Avenue between Fifty-seventh and Forty-seventh Streets on Christmas Eve, so she had to find him. O God, she prayed, let them arrest Jimmy before he hurts anyone else. There’s something wrong with him. There always has been.

Ahead of her, people were singing “Silent Night.” As she got closer, though, she realized that they weren’t actually carolers, just a crowd around a street violinist who was playing Christmas tunes.

* * *

“. . . Holy infant, so tender and mild . . .”

Brian did not join in the singing, even though “Silent Night” was his favorite and at home in Omaha he was a member of his church’s children’s choir. He wished he was there now, not in New York, and that they were getting ready to trim the Christmas tree in their own living room, and everything was the way it had been.

He liked New York and always looked forward to the summer visits with his grandmother. He had fun then. But he didn’t like this kind of visit. Not on Christmas Eve, with Dad in the hospital and Mom so sad and his brother bossing him around, even though Michael was only three years older.

Brian stuck his hands in the pockets of his jacket. They felt cold even though he had on his mittens. He looked impatiently at the giant Christmas tree across the street, on the other side of the skating rink. He knew that in a minute his mother was going to say, “All right. Now let’s get a good look at the tree.”

It was so tall, and the lights on it were so bright, and there was a big star on top of it. But Brian didn’t care about that now, or about the windows they had just seen. He didn’t want to listen to the guy playing the violin, either, and he didn’t feel like standing here.

They were wasting time. He wanted to get to the hospital and watch Mom give Dad the big St. Christopher medal that had saved Grandpa’s life when he was a soldier in World War II. Grandpa had worn it all through the war, and it even had a dent in it where a bullet had hit it.

Gran had asked Mom to give it to Dad, and even though she had almost laughed, Mom had promised but said, “Oh, Mother, Christopher was only a myth. He’s not considered a saint anymore, and the only people he helped were the ones who sold the medals everybody used to stick on dashboards.”

Gran had said, “Catherine, your father believed it helped him get through some terrible battles, and that is all that matters. He believed and so do I. Please give it to Tom and have faith.”

Brian felt impatient with his mother. If Gran believed that Dad was going to get better if he got the medal, then his mom had to give it to him. He was positive Gran was right.

“. . . sleep in heavenly peace.” The violin stopped playing, and a woman who had been leading the singing held out a basket. Brian watched as people began to drop coins and dollar bills into it.

His mother pulled her wallet out of her shoulder bag and took out two one-dollar bills. “Michael, Brian, here. Put these in the basket.”

Michael grabbed his dollar and tried to push his way through the crowd. Brian started to follow him, then noticed that his mother’s wallet hadn’t gone all the way down into her shoulder bag when she had put it back. As he watched, he saw the wallet fall to the ground.

He turned back to retrieve it, but before he could pick it up, a hand reached down and grabbed it. Brian saw that the hand belonged to a thin woman with a dark raincoat and a long ponytail.

“Mom!” he said urgently, but everyone was singing again, and she didn’t turn her head. The woman who had taken the wallet began to slip through the crowd. Instinctively, Brian began to follow her, afraid to lose sight of her. He turned back to call out to his mother again, but she was singing along now, too, “God rest you merry, gentlemen . . .” Everyone was singing so loud he knew she couldn’t hear him.

For an instant, Brian hesitated as he glanced over his shoulder at his mother. Should he run back and get her? But he thought again about the medal that would make his father better; it was in the wallet, and he couldn’t let it get stolen.

The woman was already turning the corner. He raced to catch up with her.

* * *

Why did I pick it up? Cally thought frantically as she rushed east on Forty-eighth Street toward Madison Avenue. She had abandoned her plan of walking down Fifth Avenue to find the peddler with the dolls. Instead, she headed toward the Lexington Avenue subway. She knew it would be quicker to go up to Fifty-first Street for the train, but the wallet felt like a hot brick in her pocket, and it seemed to her that everywhere she turned everyone was looking at her accusingly. Grand Central Station would be mobbed. She would get the train there. It was a safer place to go.

A squad car passed her as she turned right and crossed the street. Despite the cold, she had begun to perspire.

It probably belonged to that woman with the little boys. It was on the ground next to her. In her mind, Cally replayed the moment when she had taken in the slim young woman in the rose-colored all-weather coat that she could see was fur-lined from the turned-back sleeves. The coat obviously was expensive, as were the woman’s shoulder bag and boots; the dark hair that came to the collar of her coat was shiny. She didn’t look like she could have a care in the world.

Cally had thought, I wish I looked like that. She’s about my age and my size and we have almost the same color hair. Well, maybe by next year I can afford pretty clothes for Gigi and me.

Then she’d turned her head to catch a glimpse of the Saks windows. So I didn’t see her drop the wallet, she thought. But as she passed the woman, she’d felt her foot kick something and she’d looked down and seen it lying there.

Why didn’t I just ask if it was hers? Cally agonized. But in that instant, she’d remembered how years ago, Grandma had come home one day, embarrassed and upset. She’d found a wallet on the street and opened it and saw the name and address of the owner. She’d walked three blocks to return it even though by then her arthritis was so bad that every step hurt.

The woman who owned it had looked through it and said that a twenty-dollar bill was missing.

Grandma had been so upset. “She practically accused me of being a thief.”

That memory had flooded Cally the minute she touched the wallet. Suppose it did belong to the lady in the rose coat and she thought Cally had picked her pocket or taken money out of it? Suppose a policeman was called? They’d find out she was on probation. They wouldn’t believe her any more than they’d believed her when she lent Jimmy money and her car because he’d told her if he didn’t get out of town right away, a guy in another street gang was going to kill him.

Oh God, why didn’t I just leave the wallet there? she thought. She considered tossing it in the nearest mailbox. She couldn’t risk that. There were too many undercover cops around midtown during the holidays. Suppose one of them saw her and asked what she was doing? No, she’d get home right away. Aika, who minded Gigi along with her own grandchildren after the day-care center closed, would be bringing her home. It was getting late.

I’ll put the wallet in an envelope addressed to whoever’s name is in it and drop it in the mailbox later, Cally decided. That’s all I can do.

Cally reached Grand Central Station. As she had hoped, it was mobbed with people rushing in all directions to trains and subways, hurrying home for Christmas. She shouldered her way across the main terminal, finally making it down the steps to the entrance to the Lexington Avenue subway.

As she dropped a token in the slot and hurried for the express train to Fourteenth Street, she was unaware of the small boy who had slipped under a turnstile and was dogging her footsteps.

It was Christmas Eve in New York City. The cab slowly made its way down Fifth Avenue. It was nearly five o’clock. The traffic was heavy and the sidewalks were jammed with last-minute Christmas shoppers, homebound office workers, and tourists anxious to glimpse the elaborately trimmed store windows and the fabled Rockefeller Center Christmas tree.

It was already dark, and the sky was becoming heavy with clouds, an apparent confirmation of the forecast for a white Christmas. But the blinking lights, the sounds of carols, the ringing bells of sidewalk Santas, and the generally jolly mood of the crowd gave an appropriately festive Christmas Eve atmosphere to the famous thoroughfare.

Catherine Dornan sat bolt upright in the back of the cab, her arms around the shoulders of her two small sons. By the rigidity she felt in their bodies, she knew her mother had been right. Ten-year-old Michael’s surliness and seven-year-old Brian’s silence were sure signs that both boys were intensely worried about their dad.

Earlier that afternoon when she had called her mother from the hospital, still sobbing despite the fact that Spence Crowley, her husband’s old friend and doctor, assured her that Tom had come through the operation better than expected, and even suggested that the boys visit him at seven o’clock that night, her mother had spoken to her firmly: “Catherine, you’ve got to pull yourself together,” she had said. “The boys are so upset, and you’re not helping. I think it would be a good idea if you tried to divert them for a little while. Take them down to Rockefeller Center to see the tree, then out to dinner. Seeing you so worried has practically convinced them that Tom will die.”

This isn’t supposed to be happening, Catherine thought. With every fiber of her being she wanted to undo the last ten days, starting with that terrible moment when the phone rang and the call came from St. Mary’s Hospital. “Catherine, can you come right over? Tom collapsed while he was making his rounds.”

Her immediate impression had been that there had to be a mistake. Lean, athletic, thirty-eight-year-old men don’t collapse. And Tom always joked that pediatricians had birthright immunization to all the viruses and germs that arrived with their patients.

But Tom didn’t have immunization from the leukemia that necessitated immediate removal of his grossly enlarged spleen. At the hospital they told her that he must have been ignoring warning signs for months. And I was too stupid to notice, Catherine thought as she tried to keep her lip from quivering.

She glanced out the window and saw that they were passing the Plaza Hotel. Eleven years ago, on her twenty-third birthday, they’d had their wedding reception at the Plaza. Brides are supposed to be nervous, she thought. I wasn’t. I practically ran up the aisle.

Ten days later they’d celebrated little Christmas in Omaha, where Tom had accepted an appointment in the prestigious pediatrics unit of the hospital. We bought that crazy artificial tree in the clearance sale, she thought, remembering how Tom had held it up and said, “Attention Kmart shoppers . . .”

This year, the tree they’d selected so carefully was still in the garage, its branches roped together. They’d decided to come to New York for the surgery. Tom’s best friend, Spence Crowley, was now a prominent surgeon at Sloan-Kettering.

Catherine winced at the thought of how upset she’d been when she was finally allowed to see Tom.

The cab pulled over to the curb. “Okay, here, lady?”

“Yes, fine,” Catherine said, forcing herself to sound cheerful as she pulled out her wallet. “Dad and I brought you guys down here on Christmas Eve five years ago. Brian, I know you were too small, but Michael, do you remember?”

“Yes,” Michael said shortly as he tugged at the handle on the door. He watched as Catherine peeled a five from the wad of bills in her wallet. “How come you have so much money, Mom?”

“When Dad was admitted to the hospital yesterday, they made me take everything he had in his billfold except a few dollars. I should have sorted it out when I got back to Gran’s.”

She followed Michael out onto the sidewalk and held the door open for Brian. They were in front of Saks, near the corner of Forty-ninth Street and Fifth Avenue. Orderly lines of spectators were patiently waiting to get a closeup look at the Christmas window display. Catherine steered her sons to the back of the line. “Let’s see the windows, then we’ll go across the street and get a better look at the tree.”

Brian sighed heavily. This was some Christmas! He hated standing in line—for anything. He decided to play the game he always played when he wanted time to pass quickly. He would pretend he was already where he wanted to be, and tonight that was in his dad’s room in the hospital. He could hardly wait to see his dad, to give him the present his grandmother had said would make him get well.

Brian was so intent on getting on with the evening that when it was finally their turn to get up close to the windows, he moved quickly, barely noticing the scenes of whirling snowflakes and dolls and elves and animals dancing and singing. He was glad when they finally were off the line.

Then, as they started to make their way to the corner to cross the avenue, he saw that a guy with a violin was about to start playing and people were gathering around him. The air suddenly was filled with the sound of “Silent Night,” and people began singing.

Catherine turned back from the curb. “Wait, let’s listen for a few minutes,” she said to the boys.

Brian could hear the catch in her throat and knew that she was trying not to cry. He’d hardly ever seen Mom cry until that morning last week when someone phoned from the hospital and said Dad was real sick.

* * *

Cally walked slowly down Fifth Avenue. It was a little after five, and she was surrounded by crowds of last-minute shoppers, their arms filled with packages. There was a time when she might have shared their excitement, but today all she felt was achingly tired. Work had been so difficult. During the Christmas holidays people wanted to be home, so most of the patients in the hospital had been either depressed or difficult. Their bleak expressions reminded her vividly of her own depression over the last two Christmases, both of them spent in the Bedford correctional facility for women.

She passed St. Patrick’s Cathedral, hesitating only a moment as a memory came back to her of her grandmother taking her and her brother Jimmy there to see the crèche. But that was twenty years ago; she had been ten, and he was six. She wished fleetingly she could go back to that time, change things, keep the bad things from happening, keep Jimmy from becoming what he was now.

Even to think his name was enough to send waves of fear coursing through her body. Dear God, make him leave me alone, she prayed. Early this morning, with Gigi clinging to her, she had answered the angry pounding on her door to find Detective Shore and another officer who said he was Detective Levy standing in the dingy hallway of her apartment building on East Tenth Street and Avenue B.

“Cally, you putting up your brother again?” Shore’s eyes had searched the room behind her for signs of his presence.

The question was Cally’s first indication that Jimmy had managed to escape from Riker’s Island prison.

“The charge is attempted murder of a prison guard,” the detective told her, bitterness filling his voice. “The guard is in critical condition. Your brother shot him and took his uniform. This time you’ll spend a lot more than fifteen months in prison if you help Jimmy to escape. Accessory after the fact the second time around, when you’re talking attempted murder—or murder—of a law officer. Cally, they’ll throw the book at you.”

“I’ve never forgiven myself for giving Jimmy money last time,” Cally had said quietly.

“Sure. And the keys to your car,” he reminded her. “Cally, I warn you. Don’t help him this time.”

“I won’t. You can be sure of that. And I did not know what he had done before.” She’d watched as their eyes again shifted past her. “Go ahead,” she had cried. “Look around. He isn’t here. And if you want to put a tap on my phone, do that, too. I want you to hear me tell Jimmy to turn himself in. Because that’s all I’d have to say to him.”

But surely Jimmy won’t find me, she prayed as she threaded her way through the crowd of shoppers and sightseers. Not this time. After she had served her prison sentence, she took Gigi from the foster home. The social worker had located the tiny apartment on East Tenth Street and gotten her the job as a nurse’s aide at St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital.

This would be her first Christmas with Gigi in two years! If only she had been able to afford a few decent presents for her, she thought. A four-year-old kid should have her own new doll’s carriage, not the battered hand-me-down Cally’d been forced to get for her. The coverlet and pillow she had bought wouldn’t hide the shabbiness of the carriage. But maybe she could find the guy who was selling dolls on the street around here last week. They were only eight dollars, and she remembered that there was even one that looked like Gigi.

She hadn’t had enough money with her that day, but the guy said he’d be on Fifth Avenue between Fifty-seventh and Forty-seventh Streets on Christmas Eve, so she had to find him. O God, she prayed, let them arrest Jimmy before he hurts anyone else. There’s something wrong with him. There always has been.

Ahead of her, people were singing “Silent Night.” As she got closer, though, she realized that they weren’t actually carolers, just a crowd around a street violinist who was playing Christmas tunes.

* * *

“. . . Holy infant, so tender and mild . . .”

Brian did not join in the singing, even though “Silent Night” was his favorite and at home in Omaha he was a member of his church’s children’s choir. He wished he was there now, not in New York, and that they were getting ready to trim the Christmas tree in their own living room, and everything was the way it had been.

He liked New York and always looked forward to the summer visits with his grandmother. He had fun then. But he didn’t like this kind of visit. Not on Christmas Eve, with Dad in the hospital and Mom so sad and his brother bossing him around, even though Michael was only three years older.

Brian stuck his hands in the pockets of his jacket. They felt cold even though he had on his mittens. He looked impatiently at the giant Christmas tree across the street, on the other side of the skating rink. He knew that in a minute his mother was going to say, “All right. Now let’s get a good look at the tree.”

It was so tall, and the lights on it were so bright, and there was a big star on top of it. But Brian didn’t care about that now, or about the windows they had just seen. He didn’t want to listen to the guy playing the violin, either, and he didn’t feel like standing here.

They were wasting time. He wanted to get to the hospital and watch Mom give Dad the big St. Christopher medal that had saved Grandpa’s life when he was a soldier in World War II. Grandpa had worn it all through the war, and it even had a dent in it where a bullet had hit it.

Gran had asked Mom to give it to Dad, and even though she had almost laughed, Mom had promised but said, “Oh, Mother, Christopher was only a myth. He’s not considered a saint anymore, and the only people he helped were the ones who sold the medals everybody used to stick on dashboards.”

Gran had said, “Catherine, your father believed it helped him get through some terrible battles, and that is all that matters. He believed and so do I. Please give it to Tom and have faith.”

Brian felt impatient with his mother. If Gran believed that Dad was going to get better if he got the medal, then his mom had to give it to him. He was positive Gran was right.

“. . . sleep in heavenly peace.” The violin stopped playing, and a woman who had been leading the singing held out a basket. Brian watched as people began to drop coins and dollar bills into it.

His mother pulled her wallet out of her shoulder bag and took out two one-dollar bills. “Michael, Brian, here. Put these in the basket.”

Michael grabbed his dollar and tried to push his way through the crowd. Brian started to follow him, then noticed that his mother’s wallet hadn’t gone all the way down into her shoulder bag when she had put it back. As he watched, he saw the wallet fall to the ground.

He turned back to retrieve it, but before he could pick it up, a hand reached down and grabbed it. Brian saw that the hand belonged to a thin woman with a dark raincoat and a long ponytail.

“Mom!” he said urgently, but everyone was singing again, and she didn’t turn her head. The woman who had taken the wallet began to slip through the crowd. Instinctively, Brian began to follow her, afraid to lose sight of her. He turned back to call out to his mother again, but she was singing along now, too, “God rest you merry, gentlemen . . .” Everyone was singing so loud he knew she couldn’t hear him.

For an instant, Brian hesitated as he glanced over his shoulder at his mother. Should he run back and get her? But he thought again about the medal that would make his father better; it was in the wallet, and he couldn’t let it get stolen.

The woman was already turning the corner. He raced to catch up with her.

* * *

Why did I pick it up? Cally thought frantically as she rushed east on Forty-eighth Street toward Madison Avenue. She had abandoned her plan of walking down Fifth Avenue to find the peddler with the dolls. Instead, she headed toward the Lexington Avenue subway. She knew it would be quicker to go up to Fifty-first Street for the train, but the wallet felt like a hot brick in her pocket, and it seemed to her that everywhere she turned everyone was looking at her accusingly. Grand Central Station would be mobbed. She would get the train there. It was a safer place to go.

A squad car passed her as she turned right and crossed the street. Despite the cold, she had begun to perspire.

It probably belonged to that woman with the little boys. It was on the ground next to her. In her mind, Cally replayed the moment when she had taken in the slim young woman in the rose-colored all-weather coat that she could see was fur-lined from the turned-back sleeves. The coat obviously was expensive, as were the woman’s shoulder bag and boots; the dark hair that came to the collar of her coat was shiny. She didn’t look like she could have a care in the world.

Cally had thought, I wish I looked like that. She’s about my age and my size and we have almost the same color hair. Well, maybe by next year I can afford pretty clothes for Gigi and me.

Then she’d turned her head to catch a glimpse of the Saks windows. So I didn’t see her drop the wallet, she thought. But as she passed the woman, she’d felt her foot kick something and she’d looked down and seen it lying there.

Why didn’t I just ask if it was hers? Cally agonized. But in that instant, she’d remembered how years ago, Grandma had come home one day, embarrassed and upset. She’d found a wallet on the street and opened it and saw the name and address of the owner. She’d walked three blocks to return it even though by then her arthritis was so bad that every step hurt.

The woman who owned it had looked through it and said that a twenty-dollar bill was missing.

Grandma had been so upset. “She practically accused me of being a thief.”

That memory had flooded Cally the minute she touched the wallet. Suppose it did belong to the lady in the rose coat and she thought Cally had picked her pocket or taken money out of it? Suppose a policeman was called? They’d find out she was on probation. They wouldn’t believe her any more than they’d believed her when she lent Jimmy money and her car because he’d told her if he didn’t get out of town right away, a guy in another street gang was going to kill him.

Oh God, why didn’t I just leave the wallet there? she thought. She considered tossing it in the nearest mailbox. She couldn’t risk that. There were too many undercover cops around midtown during the holidays. Suppose one of them saw her and asked what she was doing? No, she’d get home right away. Aika, who minded Gigi along with her own grandchildren after the day-care center closed, would be bringing her home. It was getting late.

I’ll put the wallet in an envelope addressed to whoever’s name is in it and drop it in the mailbox later, Cally decided. That’s all I can do.

Cally reached Grand Central Station. As she had hoped, it was mobbed with people rushing in all directions to trains and subways, hurrying home for Christmas. She shouldered her way across the main terminal, finally making it down the steps to the entrance to the Lexington Avenue subway.

As she dropped a token in the slot and hurried for the express train to Fourteenth Street, she was unaware of the small boy who had slipped under a turnstile and was dogging her footsteps.

Product Details

- Publisher: Gallery Books (September 5, 2015)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501134067

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Silent Night Trade Paperback 9781501134067

- Author Photo (jpg): Mary Higgins Clark Photograph © Bernard Vidal(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit