Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

A “remarkably candid and sensitive” (The Wall Street Journal) memoir of more than twenty years of death-scene investigations by New York City death investigator Barbara Butcher.

Barbara Butcher was early in her recovery from alcoholism when she found an unexpected lifeline: a job at the Medical Examiner’s Office in New York City. The second woman ever hired for the role of Death Investigator in Manhattan, she was the first to last more than three months. The work was gritty, demanding, morbid, and sometimes dangerous—and she loved it.

Butcher (yes, that’s her real name, and she has heard all the jokes) spent day in and day out investigating double homicides, gruesome suicides, and most heartbreaking of all, underage rape victims who had also been murdered. In What the Dead Know, she writes with the kind of New York attitude and bravado you might expect from decades in the field, investigating more than 5,500 death scenes, 680 of which were homicides. In the opening chapter, she describes how just from sheer luck of having her arm in a cast, she avoided a boobytrapped suicide. Later in her career, she describes working the nation’s largest mass murder, the attack on 9/11, where she and her colleagues initially relied on family members’ descriptions to help distinguish among the 21,900 body parts of the victims.

This is the “breathtakingly honest, compassionate, and raw” (Patricia Cornwell), “completely unputdownable” (Adriana Trigiani, New York Times bestselling author of The Good Left Undone) real-life story of a woman who, in dealing with death every day, learned surprising lessons about life—and how some of those lessons saved her from becoming a statistic herself. Fans of Kathy Reichs, Patricia Cornwell, and true crime won’t be able to put this down.

Excerpt

“Hey, Barbara, you got a hanging man in the Three-Four Precinct. You want me to call you a driver?” Charlene’s voice was low, as if all this death business was a dirty secret. “Sure, Charlie, send me your best. Just give me five minutes to slap on some lipstick.” She laughed, as if I were going out husband-hunting instead of looking at dead people.

Putting down the phone, I felt that familiar little thrill I got when there was a decent case to investigate, something other than the natural death of an old man with heart disease found in a locked apartment. I liked to figure things out, to find clues and solve puzzles, to locate the cause behind the effect. Fortunately, that was my job. As a medicolegal investigator (MLI) with New York City’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME), I scrutinized the scenes of fatal accidents, suicides, and homicides to determine cause and manner of death. And I loved every minute of it.

This time my excitement was tempered by the aggravation of having my arm in a cast, the result of a stupid accident with a saw and a stubborn piece of wood. I would have been home recuperating if I hadn’t run out of sick time. That’s why I was in the office dealing with hospital cases rather than investigating out on the street—“on tour,” as we called it. Now I was alone on the night shift, with no choice but to answer the call, despite being one-handed and in pain. I picked up my tour bag full of equipment and—bitching, complaining, and just generally feeling sorry for myself—went out front to meet my driver.

Most OCME drivers were called by their first names: Rick or Nathan or the occasional Maureen. But Everett Wells was a dignified older gentleman we referred to as “Mr. Wells.” It was a mark of respect, even if it was at odds with his nickname, “Shake and Bake.” He earned that one for his habit of alternately stomping on the brakes and accelerator while blasting the heat. He may not have been the greatest driver among the fifteen or so at OCME, but he was my favorite. Mr. Wells was protective of me, insisting on accompanying me into buildings, while other drivers preferred to nap in the car. I was always glad when we worked a shift together.

He grabbed the tour bag from my hand. “You know I can’t let a lady carry a heavy bag,” he said. “Don’t look right.”

“Thank you, Mr. Wells. Does Mrs. Wells know you’re out with me tonight?”

“Mrs. Wells knows everything. You want Kentucky Fried after we do this?” It was either that or McDonald’s, as we could never sit down for a decent meal without my radio going off for another case.

We got to the address on the call sheet—a run-down tenement in Washington Heights, sandwiched between a bodega/numbers drop and a family-owned funeral parlor. There was no elevator, so we tromped up the stairs through the layers of smells that permeate many old New York buildings. Boiled cabbage on the first floor, Pine Sol over God knows what on the second. Then we reached the third floor.

Once you know the smell of death, you can pick it out in a flower shop. Strangely sweet with a bitter undertone, like a strawberry milkshake made with garlic. After a few weeks on the job, I could walk any block in New York and point out a building where someone was decomposing.

“This is it,” I told Mr. Wells.

“Good, he said, “because my knees are on the fritz.”

A young police officer let me into the pitch-black apartment. The streetlights were barely visible through the dingy windows, but I had a feeling the place would likely be dark even in full daylight.

“No electricity,” said the cop. “Probably didn’t pay the bill. The squad detectives already left. I’m just sitting on the body.”

“Well, that wasn’t very nice of them. I run all the way up here to hang with the boys and they couldn’t wait five minutes. Do you think they were scared?”

“Well, it is spooky as hell there in the dark with him swinging from a rope,” PO Kennedy said with disarming sincerity. He was taking me seriously, so I ran with it.

“Well, maybe you oughta get them back here. If they were afraid, I’d be a fool to go in without backup, don’t you think?” I held his eyes for a minute before smiling.

“Oh right, yeah, ha,” he said, when he realized I was teasing. “You’re not scared of anything, are ya? Is that why they call you Dr. Butcher?”

“Um, no. Butcher is my real name.”

Now it was his turn to laugh. “I know, just busting your chops. My flashlight’s almost dead. You got one?”

Kennedy told me that it looked like a straight-out suicide, that the tenant across the hall had called the police when he checked on the man for two days but got no answer. Concerned neighbors always did welfare checks in the middle of the night, or at least it seemed that way to us from the number of calls we received at 3:00 a.m. That’s the thing about death. You can smell it through tiny cracks in the walls, and it wakes you from a sound sleep.

I looked around for signs of a break-in, robbery, or fight, but the thick dust overlaying everything was undisturbed. The apartment was secured, the doors and windows locked. That in itself didn’t rule out a homicide. Even killers have keys, and most apartment doors just slam-lock without having to use one. A hanging could also be an accident, as in autoerotic asphyxiation. “Bad-boy games,” as I liked to call them.

We went around the cluttered apartment with its sad, characteristic smell that screamed of “I’ve-given-uppedness,” a sour odor of mildewed papers and despair. I took in the oak strip floors, worn past the varnish down to the pale color of sawdust. The easy chair that was anything but, springs shot through the seat. A pile of unread newspapers and an old TV Guide. I knew the place had last been painted in the ’60s because of the wall color, the same avocado green briefly popular on refrigerators back then.

My flashlight beam found a heavy, late-middle-aged white man hanging from a pipe over the bedroom doorway. His bare feet were on the floor, leaving him standing but slumped, his back hunched and knees bent. A small stool lay overturned nearby. The man’s face was swollen and red. His tongue, purple and thick, protruded between his lips, forced out by the ligature that was pulled up tight beneath his chin and hidden beneath the fat neck rolls.

I tried to turn on a lamp, but it, too, was dead. Searching with the flashlight, scanning it over the body, I could see no signs of a struggle. No defense wounds or trauma. A fight would have left scratch marks, broken or bloody fingernails, scrapes on his face. Pulling up his eyelids, I found petechial hemorrhages, the result of blood pressure building up in his head and bursting through the thin membranes of his eyeballs and undersides of the lids. When a hanging person is semi-suspended, the arteries continue pumping blood into the brain, but the softer veins are compressed, so the blood can’t get out. If he didn’t have those hemorrhages or a reddened face or a swollen, protruding tongue, I would have been suspicious. There was always the chance that he could have been killed and then strung up to make it look like a suicide. But that’s hard to do. It would have taken two strong men to hoist him up, and there would have been some disturbance to the room. A broken glass, an overturned coffee table, a rug buckled at the corner. If he had been completely suspended, his feet swinging free, the arteries would also be compressed and his face above the ligature would have been pale from the lack of blood supply. I rarely saw that in New York tenement apartments, as they have low ceilings.

I took photos while the police officer shined his flashlight on the decedent. When I started on the job in 1992, we used Polaroids, and the flash flickering over the dead man made it appear as if he were moving a little. It was eerie. I didn’t like working in the dark and wasn’t going to linger any longer than I had to, but thoroughly documenting the state of the body and the room was mandatory. As the lawyers liked to say, “If you don’t record it, it didn’t happen.”

I took overall shots of the room from all four sides, then closed in for full-body shots front and back. Zeroing in on his head and neck, I took a photo of the position of the ligature and the knot over the pipe. If anyone had questions, I’d have plenty of pictures to back up my report, to the aggravation of Laurie, our supply clerk who claimed that I was single-handedly eating up her film budget.

I checked around the apartment with a flashlight, looking for a suicide note, medical records, next-of-kin information, drugs, alcohol, eviction notice—anything that would help establish the identity of this man and offer a clue as to why he would kill himself. I didn’t find a note. Not surprising, as only about a third of people who die by suicide leave one. Nor did I find evidence of a “life disturbance,” such as a lawsuit notice, medical diagnosis, or Dear John letter. But the reasons for taking your own life run deep. There’s often no obvious precipitating event.

I was satisfied that this was a suicide, nothing unusual. The gloomy apartment spoke volumes about depression and despair. There were no signs that this person had been enjoying his life. In fact, there were few signs of any life at all. I would have liked to find something to explain why he wanted to die, but in the dark mess of his home, that was impossible. Maybe having Con Ed turn off the power was the final straw.

I grabbed the Buck knife from my case and pulled the stool upright next to the hanging man so I could cut him down. Usually, I would hold the ligature with my left hand, cut high above the knot with my right, and guide him to the ground as gently as I could. I did this to preserve the ligature and the knot around his neck for the pathologist, and to avoid postmortem injuries that might confuse things in the autopsy room.

A body is a heavy thing. Quite literally, a deadweight. Even a strong man couldn’t lower a body with one hand, but I could steady and ease him down a bit. Once you’ve done this a few times, you can anticipate the weight, know what’s coming so that the decedent doesn’t land with a thud. Damn… I couldn’t do it. My left arm and hand were in a cast. Mr. Wells, who was waiting in the hallway, certainly couldn’t climb up there, and it wasn’t appropriate to ask the police officer to do my job—union rules and all that. No problem. The morgue wagon would be arriving soon with two strong attendants to pick up the body. They would take care of things for me. I radioed the office and explained the situation, asking the morgue team to cut above the knot and make sure to let him down easy.

I signed the toe tag for the police officer to release the scene to PD, and also to prove that I was there. A colleague had recently been accused of doing “drive-by investigations,” the joke being that he did such a perfunctory job that he never left the car, just yelled up to the police officer: “Looks like a natural? Throw me down the toe tag!”

After finishing the case, there was no time to sit down with fried chicken, so Mr. Wells and I ate drive-thru cheeseburgers in the car on 125th Street. Fast food was fresher uptown, where people stayed out at night.

Mr. Wells sniffed. “Hmph. Randy always takes me to a café for lunch. Knows all the nice places. He’s sophisticated, you know.”

“Well, if I ever get the day shift back, I’ll take you to a damn bistro, all right?” My throbbing arm was making me grumpy.

We headed back to the office, Mr. Wells muttering about the unfairness of my having to work with my injury. “Makes no sense to me,” he said. “Fools will get you hurt worse.”

Back at my desk with the Polaroids and notes spread out, I began writing up the report for the forensic pathologist (the medical examiner, or ME) who would be doing the autopsy the next morning. Contrary to most TV shows, pathologists rarely, if ever, go out to investigate a death scene. Their days are highly structured and awfully busy with autopsies, toxicology, tissue examination, and brain dissection. Not to mention a whole raft of paperwork. It wasn’t like the ME could leave the table in the middle of autopsy to run out to a crime scene. Although I started my day in the office, much of it was spent out on the street, responding to scenes as needed.

In the old days, pathologists depended on the police or elected coroners (who were often funeral directors) to investigate the body at the scene. But without a medical background, they could be fooled by the artifacts of death and decay, or the natural sequelae of disease. It was my mentor Dr. Charles Hirsch who had the idea of training experienced physician assistants in investigation and forensics both in-house and at NYPD. The forensic pathologist’s job is to determine cause and manner of death. Taking the case of a gunshot wound, for example, while the cause of death might be apparent, the manner of death could be either a homicide, suicide, or accident. It’s the MLI’s job to investigate the circumstances at the scene: Were there signs of violence? Was the apartment secured? Was there evidence of natural disease? Most of all, did the story make sense according to the physical evidence? We are the medical examiner’s eyes and ears. Without a good scene investigation, the ME would be flying blind in the autopsy room.

Going over the scene photos, I could see that the body and the room were pretty well lit up by the camera flash. Actually, I could discern more detail in the Polaroids than I could in the apartment itself. That wasn’t surprising. When you’re on scene, you’re absorbing data in the moment. Sometimes, in order to analyze what’s going on, you’ve got to take a step back from the room. You learn to think outside the box when the box contains a dead person. Especially when the box is pitch-black and you can’t see a damned thing. The place was even dingier on film, the furniture the color of mud. Behind the hanging man I could see an unmade bed, the yellowed sheets unfamiliar with a washing machine. Trailing from behind the decedent’s head was a long orange extension cord, the kind you use outdoors. That’s what he used to hang himself, a smart choice as it wouldn’t break during his final act. But the next photo—the cord was plugged into a wall socket. A live wire?

Shit. I thought the electricity was off.

I called the apartment phone, fingers trembling, praying the cop would answer it. C’mon, c’mon… pick up. I prayed extra hard that the morgue techs hadn’t arrived yet.

“Uh, hullo?”

“Listen, don’t let anyone touch the dead guy.”

“Copy that. What’s up?”

“I need you to go check the lamps and see if the light bulbs are screwed in.”

“If the light bulbs are—?”

“Yes… check if the light bulbs are screwed in. I’ll hold on.”

I heard the phone clunk down on a table. A moment later Kennedy came back. “Let there be light!” he said. I let out a deep breath. “What the hell’s going on? How did you know the light bulbs were unscrewed?”

After making sure that the morgue techs hadn’t arrived, I told him what I had figured out, that the guy had rigged things so that anyone cutting him down would be electrocuted. Making the apartment pitch-dark, giving the impression that the electricity was off by leaving the bulbs in but unscrewed, hooking the extension cord up to a socket away from the body—all that took thought. I held on while Kennedy unplugged the dead man and checked for other booby traps.

This was an angry suicide.

This guy was so pissed off at the world that killing himself wasn’t enough; he wanted to take someone with him, to electrocute whoever cut him down. And he had planned it all meticulously. If I hadn’t had my arm in a cast—something I’d been bitching and complaining about for days—I might have gone down with him.

The small misfortune of a sawed-through tendon probably saved my life—I thought about this for a while and filed it away to contemplate later—there must be an important lesson in there somewhere. I was always doing that, saving lessons for a rainy day. But damn. I kept thinking about the hanging man and why he would want to hurt and even kill someone else. Was it a case of misery loves company, that he was so wretched that it somehow helped him to know that others would suffer, too? Did he want to punish the world for ignoring his pain? Or trying to make a mark, hoping people would talk about him? Perhaps he was just a lonely person who wanted to be remembered for something, anything. It made me think of all those cases where a man shoots into a crowd of strangers before putting a bullet in his own head. Why not just kill yourself and be done with it?

That question. Why not just kill yourself and be done with it? It was one I had asked myself not so long before. About four years prior, I had hit rock bottom. A disgraced alcoholic, I was living in a shabby little studio, working off the books in a button store off Madison Avenue. It was all I felt I deserved.

I had been miserable in my early teens, suffering from depression and suicidal impulses from an early age. I had been an anxious, fearful child, and the hormones of puberty didn’t help. When a new friend came along in high school who showed me a life of getting high on drugs, drinking, and sex—a kind of fun I’d never had—I fell for it hard. I wanted to be high all the time. Sure, the good times were transient and troublesome, but I craved the distraction. So what if my habits prevented me from studying or applying to college; I felt good in the moment. No, I felt great.

I did get a scholarship for state college, but I was too busy partying and never filled out the paperwork. After high school, I worked low-level jobs, making just enough to rent a room over a dental lab at $70 a month. It was next to the Massapequa Fire Department and across from the Long Island Rail Road station, so I didn’t get much sleep. I shared one bathroom with six strangers. There was no kitchen, only a hot plate, so I didn’t eat much either. If I had enough money for the cover charge and a few drinks at the disco, I was okay.

Thank God for guides, those people who see in you what you fail to see in yourself. The woman I worked for, Celia Strow, noticed that I was smart and capable, and wondered why I didn’t make something of myself. Ms. Strow was the director of a nursing home on Long Island, and she had hired me to take care of the supply stockroom and to conduct a form of “reality orientation therapy” for patients with dementia. That meant holding up flash cards with the day and date, asking people if they knew who the president was. I would remind these confused old people that they were in a home, that their spouses had died, that their children lived elsewhere—things no one wants to remember.

Ms. Strow told me about a job called physician assistant, kind of like a junior doctor and requiring only four years of study. The money was good, and I would have an actual career. Sounded okay to me. I applied to only one school, Stony Brook University, because it was too much trouble to fill out multiple applications. The night before my interview, I went out to a club and got drunk. I arrived home at 5:00 in the morning; my interview was at 9:00 a.m. Stony Brook was an hour’s drive. I figured, what the hell, I could work in a short nap. I woke with a start, not sure where I was and already late. With no time to shower or change, I sped out of there stinking of cigarettes and no-label gin, barely able to keep my bloodshot eyes open.

Stony Brook didn’t take me—no surprise there. I was embarrassed by the rejection and disappointed in myself for getting drunk, but somehow I got it together the next year and was admitted to Long Island University in Brooklyn. It was an urban campus, with lectures held in the old Brooklyn Paramount Theater where the glorious rococo ceiling distracted me from hearing about the function of the spleen. Though there were no ivy-covered walls or sororities, I was finally in college and proud of myself. My drinking slowed down as I reawakened to the pleasure of learning, of knowing things. The course work was a blend of science and practical training: anatomy and physiology, chemistry and pathology, how to suture a wound, pass a nasogastric tube, interpret an EKG, and set a broken arm. It was the lectures on diagnosis that really woke me up—this was important stuff. I could investigate symptoms, build a knowledge base of diseases, figure things out, solve a puzzle, and help people. It rekindled my childhood love of science and gave me a sense that I could do something important. I could be useful. I could be somebody.

This was probably my first experience of a “God shot,” that providential moment when a higher power does something unexpected and fortunate. Maybe a stranger bumps you hard as you’re about to step into the path of a car. Or you meet someone in a coffee shop who gives you meaningful advice over coffee and a toasted corn muffin. If Celia Strow hadn’t encouraged me, I would likely still be working in that nursing home, telling people things they wanted to forget.

As a newly minted physician assistant, I got a great job in surgery at a hospital in the South Bronx with plenty of action to keep me busy. Back then, it was a scrappy place without a residency program, so they let PAs do everything. I was also volunteering at a women’s free clinic on St. Mark’s Place, doing primary care and Pap smears with four inspiring women physicians. It was there that I made a friend who let me take over the lease on her apartment when she moved. A rent-stabilized one-bedroom in a West Village brownstone, it had all the original details: fireplace, crown moldings, and a transom over the bedroom door. I didn’t care that everything was covered with decades of paint. This was my first Olde New York–style apartment, and it thrilled me.

After a couple of jobs and promotions, including a stint working at a Kaiser clinic in California, I earned a master’s in public health at Columbia University. This was when AIDS first emerged, a public health mystery and a nightmare. I studied epidemiology, the investigatory arm of medicine—where did this strange disease come from, what was causing it, who was getting it and why?

I started a promising career as a hospital administrator and renovated my apartment, revealing the historical details that made it so special. Things like the fireplace—why was it so shallow? Aha—it was for burning coal back before central heating was the norm. The side panels of the deep windows seemed hollow—what was in there? Fancy wooden shutters to close against the cold winters. Beautiful. I was noticing things in my surroundings and in myself. Feeling good about my home and my job, I was actually starting to believe that I had something to offer. As corny as it sounds, I felt as if I were becoming a good citizen. I was happy and fulfilled and in love with a wonderful woman. But addiction doesn’t just go away by itself, and after a few years the devil got back into me. I fell for the wrong person, started drinking heavily again, and broke up with my lovely, intelligent, and honorable partner of seven years. I was in search of excitement, and I got it in spades. Drugs, drinking, a lot of sex. I lied to people I cared for, was manipulative and uncaring. I cheated on everyone. I liked being good at things, and I was good at being an addict. I ruined everything.

One tumultuous affair led to another, and I went into a tailspin of erratic behavior. I got fired from my excellent job. My landlady was so impressed with the work I had done on the apartment, she wanted it for herself. She refused to renew my lease, effectively kicking me out. That forced me to move into a crummy studio on the Upper West Side. My latest love affair ended badly. Then my twenty-four-year-old brother John Luke died of a drug overdose. The losses were unbearable, and I couldn’t take it anymore. I descended into a deep and hideous depression. I had nothing. I was nothing. Why not kill myself and be done with it?

So I got drunk and rehearsed my suicide. Using a gun I had bought in California a few years before, I held the unloaded .32 revolver to my head, pulling the trigger, practicing so that I wouldn’t jerk my head away when it was time. I dry-fired once or twice before passing out from several glasses of vodka. One of the few times I could say drinking saved my life.

My life looked like an EKG: up and down spikes of things going well, things falling apart. For more than a year, I sank slowly to the bottom. One night, I drank to the point of blacking out and woke up on the floor, tangled in damp sheets, smelling of foul sweat. My forehead was cut and bruised, the result of falling up the stairs, hard to do unless blind drunk. The heaving sickness—it was much more than nausea—was overwhelming. The pounding in my head scared me. This was like no hangover I had ever experienced. Even the pigeons fussing on my window ledge drilled through my skull. I wanted to be dead. Something had to give.

Why We Love It

“There are zillions of fans of murder mysteries, but this is the real thing. Even better, this is the real thing with attitude. Barbara Butcher (you have to love that name) is no-nonsense, which is the only way you can be when you are dealing with cops and detectives at a crime scene. They controlled the scene, but she was in charge of the body. And she made sure they knew it. The book is written with a tough-guy attitude, but it quickly becomes evident that this is a veneer that is necessary for the job. Underneath it is the real Barbara, someone recovering from addiction, someone who understands human frailty and can show compassion when necessary—but can also be as hard and cold as the situation requires. You will love the voice in this book. I know I do.”

—Bob B., VP, Executive Editor, on What the Dead Know

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (June 20, 2023)

- Length: 288 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982179380

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Reading this memoir is like watching an episode of CSI with your dry, brassy best friend.”

– NPR "Books We Love"

“Butcher’s remarkably candid and sensitive memoir reveals how she learned to navigate a heart-wrenching line of work and to overcome her own demons.”

– Tom Nolan, The Wall Street Journal

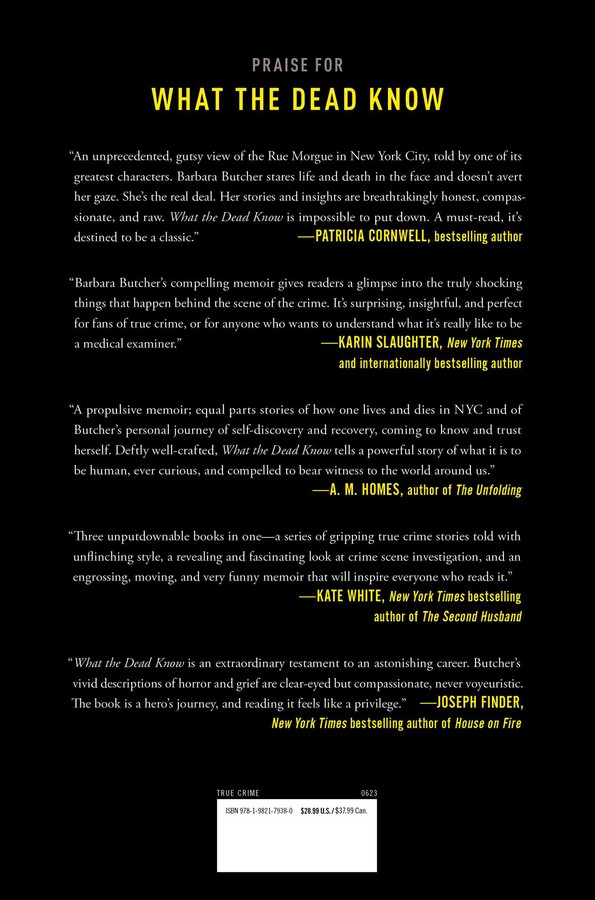

"An unprecedented gutsy view of the Rue Morgue in New York City, told by one of its greatest characters. Barbara Butcher stares life and death in the face and doesn’t avert her gaze. She’s the real deal. Her stories and insights are breathtakingly honest, compassionate, and raw. What the Dead Know is impossible to put down. A must read, it's destined to be a classic."

– Patricia Cornwell

“What the Dead Know is wise and deep and completely unputdownable. Barbara Butcher's memoir is about finding home within yourself. It’s fantastic."

– Adriana Trigiani, New York Times bestselling author of The Good Left Undone

“Butcher chronicles her career path and her journey to sobriety in unflinching detail, while her voice remains deliberate and measured, occasionally slipping into what sounds like a half-smirk when cracking a joke….She has a way with words, telling stories that are at turns hilarious, thought-provoking and, as might be expected, disturbing. This is a story of trauma, yes, but it’s also a glimpse into the dark side of a city that most never see up close.”

– New York Times Book Review

"Barbara Butcher’s compelling memoir gives readers a glimpse into the truly shocking things that happen behind the scene of the crime. It’s surprising, insightful, and perfect for fans of true crime, or for anyone who wants to understand what it’s really like to be a medical examiner."

– Karin Slaughter, New York Times and Internationally Bestselling Author

“A propulsive memoir; equal parts stories of how one lives and dies in NYC and Butcher’s personal journey of self-discovery and recovery, coming to know, trust herself. Deftly well crafted, What The Dead Know tells a powerful story of what it is to be human, ever curious, and compelled to bear witness to the world around us.”

– A.M. Homes, author of The Unfolding

“In this riveting memoir, Barbara Butcher writes unflinchingly about death and loss with stories gleaned from decades of experience in the New York City Medical Examiner’s Offices, but she also writes honestly and with surprising humor about her own life’s challenges and recoveries. Reading this book felt like getting to know a new, fascinating friend.”

– Alafair Burke, New York Times bestselling author of Find Me

"Barbara Butcher’s What the Dead Know is three unputdownable books in one—a series of gripping true crime stories told with unflinching style, a revealing and fascinating look at crime scene investigation, and an engrossing, moving, and very funny memoir that will inspire everyone who reads it."

– Kate White, New York Times bestselling author of The Second Husband

“What the Dead Know offers an unflinching look at the lives and deaths investigated by medicolegal death investigator Barbara Butcher in New York City. Her stories capture the integrity and empathy necessary for a professional career dedicated to understanding death, with a greater purpose: to support the living.”

– Judy Melinek, M.D., author of Working Stiff

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): What the Dead Know Hardcover 9781982179380

- Author Photo (jpg): Barbara Butcher Photograph by Anthony Robert Grasso(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit