Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

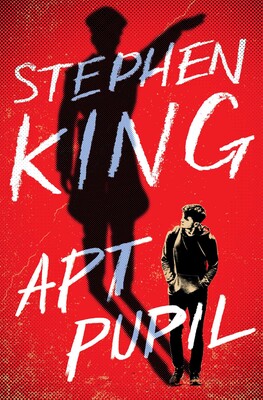

#1 New York Times bestselling author Stephen King’s timeless coming-of-age novella, Apt Pupil—published in his 1982 story collection Different Seasons and made into a 1998 Tristar movie starring Ian McKellan and Brad Renfro—now available for the first time as a standalone publication.

If you don’t believe in the existence of evil, you have a lot to learn.

Todd Bowden is an apt pupil. Good grades, good family, a paper route. But he is about to meet a different kind of teacher, Mr. Dussander, and to learn all about Dussander’s dark and deadly past…a decades-old manhunt Dussander has escaped to this day. Yet Todd doesn’t want to turn his teacher in. Todd wants to know more. Much more. He is about to face his fears and learn the real meaning of power—and the seductive lure of evil.

A classic story from Stephen King, Apt Pupil reveals layers upon layers of deception—and horror—as finally there is only one left standing.

If you don’t believe in the existence of evil, you have a lot to learn.

Todd Bowden is an apt pupil. Good grades, good family, a paper route. But he is about to meet a different kind of teacher, Mr. Dussander, and to learn all about Dussander’s dark and deadly past…a decades-old manhunt Dussander has escaped to this day. Yet Todd doesn’t want to turn his teacher in. Todd wants to know more. Much more. He is about to face his fears and learn the real meaning of power—and the seductive lure of evil.

A classic story from Stephen King, Apt Pupil reveals layers upon layers of deception—and horror—as finally there is only one left standing.

Excerpt

Apt Pupil 1

He looked like the total all-American kid as he pedaled his twenty-six-inch Schwinn with the apehanger handlebars up the residential suburban street, and that’s just what he was: Todd Bowden, thirteen years old, five-feet-eight and a healthy one hundred and forty pounds, hair the color of ripe corn, blue eyes, white even teeth, lightly tanned skin marred by not even the first shadow of adolescent acne.

He was smiling a summer vacation smile as he pedaled through the sun and shade not too far from his own house. He looked like the kind of kid who might have a paper route, and as a matter of fact, he did—he delivered the Santo Donato Clarion. He also looked like the kind of kid who might sell greeting cards for premiums, and he had done that, too. They were the kind that come with your name printed inside—JACK AND MARY BURKE, OR DON AND SALLY, OR THE MURCHISONS. He looked like the sort of boy who might whistle while he worked, and he often did so. He whistled quite prettily, in fact. His dad was an architectural engineer who made forty thousand dollars a year. His mom had majored in French in college and had met Todd’s father when he desperately needed a tutor. She typed manuscripts in her spare time. She had kept all of Todd’s old school report cards in a folder. Her favorite was his final fourth-grade card, on which Mrs. Upshaw had scratched: “Todd is an extremely apt pupil.” He was, too. Straight A’s and B’s all the way up the line. If he’d done any better—straight A’s, for example—his friends might have begun to think he was weird.

Now he brought his bike to a halt in front of 963 Claremont Street and stepped off it. The house was a small bungalow set discreetly back on its lot. It was white with green shutters and green trim. A hedge ran around the front. The hedge was well-watered and well-clipped.

Todd brushed his blonde hair out of his eyes and walked the Schwinn up the cement path to the steps. He was still smiling, and his smile was open and expectant and beautiful. He pushed down the bike’s kickstand with the toe of one Nike running-shoe and then picked the folded newspaper off the bottom step. It wasn’t the Clarion; it was the LA. Times. He put it under his arm and mounted the steps. At the top was a heavy wooden door with no window inside of a latched screen door. There was a doorbell on the right-hand doorframe, and below the bell were two small signs, each neatly screwed into the wood and covered with protective plastic so they wouldn’t yellow or waterspot. German efficiency, Todd thought, and his smile widened a little. It was an adult thought, and he always mentally congratulated himself when he had one of those.

The top sign said ARTHUR DENKER.

The bottom one said NO SOLICITORS, NO PEDDLERS, NO SALESMEN.

Smiling still, Todd rang the bell.

He could barely hear its muted burring, somewhere far off inside the small house. He took his finger off the bell and cocked his head a little, listening for footsteps. There were none. He looked at his Timex watch (one of the premiums he had gotten for selling personalized greeting cards) and saw that it was twelve past ten. The guy should be up by now. Todd himself was always up by seven-thirty at the latest, even during summer vacation. The early bird catches the worm.

He listened for another thirty seconds and when the house remained silent he leaned on the bell, watching the sweep second hand on his Timex as he did so. He had been pressing the doorbell for exactly seventy-one seconds when he finally heard shuffling footsteps. Slippers, he deduced from the soft wish-wish sound. Todd was into deductions. His current ambition was to become a private detective when he grew up.

“All right! All right!” the man who was pretending to be Arthur Denker called querulously. “I’m coming! Let it go! I’m coming!”

Todd stopped pushing the doorbell button.

A chain and bolt rattled on the far side of the windowless inner door. Then it was pulled open.

An old man, hunched inside a bathrobe, stood looking out through the screen. A cigarette smouldered between his fingers. Todd thought the man looked like a cross between Albert Einstein and Boris Karloff. His hair was long and white but beginning to yellow in an unpleasant way that was more nicotine than ivory. His face was wrinkled and pouched and puffy with sleep, and Todd saw with some distaste that he hadn’t bothered shaving for the last couple of days. Todd’s father was fond of saying, “A shave puts a shine on the morning.” Todd’s father shaved every day, whether he had to work or not.

The eyes looking out at Todd were watchful but deeply sunken, laced with snaps of red. Todd felt an instant of deep disappointment. The guy did look a little bit like Albert Einstein, and he did look a little bit like Boris Karloff, but what he looked like more than anything else was one of the seedy old winos that hung around down by the railroad yard.

But of course, Todd reminded himself, the man had just gotten up. Todd had seen Denker many times before today (although he had been very careful to make sure that Denker hadn’t seen him, no way, Jose), and on his public occasions, Denker looked very natty, every inch an officer in retirement, you might say, even though he was seventy-six if the articles Todd had read at the library had his birth-date right. On the days when Todd had shadowed him to the Shoprite where Denker did his shopping or to one of the three movie theaters on the bus line—Denker had no car—he was always dressed in one of three neatly kept suits, no matter how warm the weather. If the weather looked threatening he carried a furled umbrella under one arm like a swagger stick. He sometimes wore a trilby hat. And on the occasions when Denker went out, he was always neatly shaved and his white moustache (worn to conceal an imperfectly corrected harelip) was carefully trimmed.

“A boy,” he said now. His voice was thick and sleepy. Todd saw with new disappointment that his robe was faded and tacky. One rounded collar point stood up at a drunken angle to poke at his wattled neck. There was a splotch of something that might have been chili or possibly A-l Steak Sauce on the left lapel, and he smelled of cigarettes and stale booze.

“A boy,” he repeated. “I don’t need anything, boy. Read the sign. You can read, can’t you? Of course you can. All American boys can read. Don’t be a nuisance, boy. Good day.”

The door began to close.

He might have dropped it right there, Todd thought much later on one of the nights when sleep was hard to find. His disappointment at seeing the man for the first time at close range, seeing him with his street-face put away—hanging in the closet, you might say, along with his umbrella and his trilby—might have done it. It could have ended in that moment, the tiny, unimportant snicking sound of the latch cutting off everything that happened later as neatly as a pair of shears. But, as the man himself had observed, he was an American boy, and he had been taught that persistence is a virtue.

“Don’t forget your paper, Mr. Dussander,” Todd said, holding the Times out politely.

The door stopped dead in its swing, still inches from the jamb. A tight and watchful expression flitted across Kurt Dussander’s face and was gone at once. There might have been fear in that expression. It was good, the way he had made that expression disappear, but Todd was disappointed for the third time. He hadn’t expected Dussander to be good; he had expected Dussander to be great.

Boy, Todd thought with real disgust. Boy oh boy.

He pulled the door open again. One hand, bunched with arthritis, unlatched the screen door. The hand pushed the screen door open just enough to wriggle through like a spider and close over the edge of the paper Todd was holding out. The boy saw with distaste that the old man’s fingernails were long and yellow and horny. It was a hand that had spent most of its waking hours holding one cigarette after another. Todd thought smoking was a filthy dangerous habit, one he himself would never take up. It really was a wonder that Dussander had lived as long as he had.

The old man tugged. “Give me my paper.”

“Sure thing, Mr. Dussander.” Todd released his hold on the paper. The spider-hand yanked it inside. The screen closed.

“My name is Denker,” the old man said. “Not this Doo-Zander. Apparently you cannot read. What a pity. Good day.”

The door started to close again. Todd spoke rapidly into the narrowing gap. “Bergen-Belsen, January 1943 to June 1943. Auschwitz, June 1943 to June of 1944, Unterkommandant. Patin—”

The door stopped again. The old man’s pouched and pallid face hung in the gap like a wrinkled, half-deflated balloon. Todd smiled.

“You left Patin just ahead of the Russians. You got to Buenos Aires. Some people say you got rich there, investing the gold you took out of Germany in the drug trade. Whatever, you were in Mexico City from 1950 to 1952. Then—”

“Boy, you are crazy like a cuckoo bird.” One of the arthritic fingers twirled circles around a misshapen ear. But the toothless mouth was quivering in an infirm, panicky way.

“From 1952 until 1958, I don’t know,” Todd said, smiling more widely still. “No one does, I guess, or at least they’re not telling. But an Israeli agent spotted you in Cuba, working as the concierge in a big hotel just before Castro took over. They lost you when the rebels came into Havana. You popped up in West Berlin in 1965. They almost got you.” He pronounced the last two words as one: gotcha. At the same time he squeezed all of his fingers together into one large, wriggling fist. Dussander’s eyes dropped to those well-made and well-nourished American hands, hands that were made for building soapbox racers and Aurora models. Todd had done both. In fact, the year before, he and his dad had built a model of the Titanic. It had taken almost four months, and Todd’s father kept it in his office.

“I don’t know what you are talking about,” Dussander said. Without his false teeth, his words had a mushy sound Todd didn’t like. It didn’t sound . . . well, authentic. Colonel Klink on Hogan’s Heroes sounded more like a Nazi than Dussander did. But in his time he must have been a real whiz. In an article on the death-camps in Men’s Action, the writer had called him The Blood-Fiend of Patin. “Get out of here, boy. Before I call the police.”

“Gee, I guess you better call them, Mr. Dussander. Or Herr Dussander, if you like that better.” He continued to smile, showing perfect teeth that had been fluoridated since the beginning of his life and bathed thrice a day in Crest toothpaste for almost as long. “After 1965, no one saw you again . . . until I did, two months ago, on the downtown bus.”

“You’re insane.”

“So if you want to call the police,” Todd said, smiling, “you go right ahead. I’ll wait on the stoop. But if you don’t want to call them right away, why don’t I come in? We’ll talk.”

There was a long moment while the old man looked at the smiling boy. Birds twitted in the trees. On the next block a power mower was running, and far off, on busier streets, horns honked out their own rhythm of life and commerce.

In spite of everything, Todd felt the onset of doubt. He couldn’t be wrong, could he? Was there some mistake on his part? He didn’t think so, but this was no schoolroom exercise. It was real life. So he felt a surge of relief (mild relief, he assured himself later) when Dussander said: “You may come in for a moment, if you like. But only because I do not wish to make trouble for you, you understand?”

“Sure, Mr. Dussander,” Todd said. He opened the screen and came into the hall. Dussander closed the door behind them, shutting off the morning.

The house smelled stale and slightly malty. It smelled the way Todd’s own house smelled sometimes the morning after his folks had thrown a party and before his mother had had a chance to air it out. But this smell was worse. It was lived-in and ground-in. It was liquor, fried food, sweat, old clothes, and some stinky medicinal smell like Vick’s or Mentholatum. It was dark in the hallway, and Dussander was standing too close, his head hunched into the collar of his robe like the head of a vulture waiting for some hurt animal to give up the ghost. In that instant, despite the stubble and the loosely hanging flesh, Todd could see the man who had stood inside the black SS uniform more clearly than he had ever seen him on the street. And he felt a sudden lancet of fear slide into his belly. Mild fear, he amended later.

“I should tell you that if anything happens to me—” he began, and then Dussander shuffled past him and into the living room, his slippers wish-wishing on the floor. He flapped a contemptuous hand at Todd, and Todd felt a flush of hot blood mount into his throat and cheeks.

Todd followed him, his smile wavering for the first time. He had not pictured it happening quite like this. But it would work out. Things would come into focus. Of course they would. Things always did. He began to smile again as he stepped into the living room.

It was another disappointment—and how!—but one he supposed he should have been prepared for. There was of course no oil portrait of Hitler with his forelock dangling and eyes that followed you. No medals in cases, no ceremonial sword mounted on the wall, no Luger or PPK Walther on the mantel (there was, in fact, no mantel). Of course, Todd told himself, the guy would have to be crazy to put any of those things out where people could see them. Still, it was hard to put everything you saw in the movies or on TV out of your head. It looked like the living room of any old man living alone on a slightly frayed pension. The fake fireplace was faced with fake bricks. A Westclox hung over it. There was a black and white Motorola TV on a stand; the tips of the rabbit ears had been wrapped in aluminum foil to improve reception. The floor was covered with a gray rug; its nap was balding. The magazine rack by the sofa held copies of National Geographic, Reader’s Digest, and the L.A. Times. Instead of Hitler or a ceremonial sword hung on the wall, there was a framed certificate of citizenship and a picture of a woman in a funny hat. Dussander later told him that sort of hat was called a cloche, and they had been popular in the twenties and thirties.

“My wife,” Dussander said sentimentally. “She died in 1955 of a lung disease. At that time I was working at the Menschler Motor Works in Essen. I was heartbroken.”

Todd continued to smile. He crossed the room as if to get a better look at the woman in the picture. Instead of looking at the picture, he fingered the shade on a small table-lamp.

“Stop that!” Dussander barked harshly. Todd jumped back a little.

“That was good,” he said sincerely. “Really commanding. It was Ilse Koch who had the lampshades made out of human skin, wasn’t it? And she was the one who had the trick with the little glass tubes.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Dussander said. There was a package of Kools, the kind with no filter, on top of the TV. He offered them to Todd. “Cigarette?” he asked, and grinned. His grin was hideous.

“No. They give you lung cancer. My dad used to smoke, but he gave it up. He went to Smokenders.”

“Did he.” Dussander produced a wooden match from the pocket of his robe and scratched it indifferently on the plastic case of the Motorola. Puffing, he said: “Can you give me one reason why I shouldn’t call the police and tell them of the monstrous accusations you’ve just made? One reason? Speak quickly, boy. The telephone is just down the hall. Your father would spank you, I think. You would sit for dinner on a cushion for a week or so, eh?”

“My parents don’t believe in spanking. Corporal punishment causes more problems than it cures.” Todd’s eyes suddenly gleamed. “Did you spank any of them? The women? Did you take off their clothes and—”

With a muffled exclamation, Dussander started for the phone.

Todd said coldly: “You better not do that.”

Dussander turned. In measured tones that were spoiled only slightly by the fact that his false teeth were not in, he said: “I tell you this once, boy, and once only. My name is Arthur Denker. It has never been anything else; it has not even been Americanized. I was in fact named Arthur by my father, who greatly admired the stories of Arthur Conan Doyle. It has never been Doo-Zander, or Himmler, or Father Christmas. I was a reserve lieutenant in the war. I never joined the Nazi party. In the battle of Berlin I fought for three weeks. I will admit that in the late thirties, when I was first married, I supported Hitler. He ended the depression and returned some of the pride we had lost in the aftermath of the sickening and unfair Treaty of Versailles. I suppose I supported him mostly because I got a job and there was tobacco again, and I didn’t need to hunt through the gutters when I needed to smoke. I thought, in the late thirties, that he was a great man. In his own way, perhaps he was. But at the end he was mad, directing phantom armies at the whim of an astrologer. He even gave Blondi, his dog, a death-capsule. The act of a madman; by the end they were all madmen, singing the ‘Horst Wessel Song’ as they fed poison to their children. On May 2nd, 1945, my regiment gave up to the Americans. I remember that a private soldier named Hackermeyer gave me a chocolate bar. I wept. There was no reason to fight on; the war was over, and really had been since February. I was interned at Essen and was treated very well. We listened to the Nuremberg trials on the radio, and when Goering committed suicide, I traded fourteen American cigarettes for half a bottle of Schnaps and got drunk. When I was released, I put wheels on cars at the Essen Motor Works until 1963, when I retired. Later I emigrated to the United States. To come here was a lifelong ambition. In 1967 I became a citizen. I am an American. I vote. No Buenos Aires. No drug dealing. No Berlin. No Cuba.” He pronounced it Koo-ba. “And now, unless you leave, I make my telephone call.”

He watched Todd do nothing. Then he went down the hall and picked up the telephone. Still Todd stood in the living room, beside the table with the small lamp on it.

Dussander began to dial. Todd watched him, his heart speeding up until it was drumming in his chest. After the fourth number, Dussander turned and looked at him. His shoulders sagged. He put the phone down.

“A boy,” he breathed, “A boy.”

Todd smiled widely but rather modestly.

“How did you find out?”

“One piece of luck and a lot of hard work,” Todd said. “There’s this friend of mine, Harold Pegler his name is, only all the kids call him Foxy. He plays second base for our team. His dad’s got all these magazines out in his garage. Great big stacks of them. War magazines. They’re old. I looked for some new ones, but the guy who runs the newsstand across from the school says most of them went out of business. In most of them there’s pictures of krauts—German soldiers, I mean—and Japs torturing these women. And articles about the concentration camps. I really groove on all that concentration camp stuff.”

“You . . . groove on it.” Dussander was staring at him, one hand rubbing up and down on his cheek, producing a very small sandpapery sound.

“Groove. You know. I get off on it. I’m interested.”

He remembered that day in Foxy’s garage as clearly as anything in his life—more clearly, he suspected. He remembered in the fifth grade, before Careers Day, how Mrs. Anderson (all the kids called her Bugs because of her big front teeth) had talked to them about what she called finding YOUR GREAT INTEREST.

“It comes all at once,” Bugs Anderson had rhapsodized. “You see something for the first time, and right away you know you have found YOUR GREAT INTEREST. It’s like a key turning in a lock. Or falling in love for the first time. That’s why Careers Day is so important, children—it may be the day on which you find YOUR GREAT INTEREST.” And she had gone on to tell them about her own GREAT INTEREST, which turned out not to be teaching the fifth grade but collecting nineteenth-century postcards.

Todd had thought Mrs. Anderson was full of bullspit at the time, but that day in Foxy’s garage, he remembered what she had said and wondered if maybe she hadn’t been right after all.

The Santa Anas had been blowing that day, and to the east there were brush-fires. He remembered the smell of burning, hot and greasy. He remembered Foxy’s crewcut, and the flakes of Butch Wax clinging to the front of it. He remembered everything.

“I know there’s comics here someplace,” Foxy had said. His mother had a hangover and had kicked them out of the house for making too much noise. “Neat ones. They’re Westerns, mostly, but there’s some Turok, Son of Stone and—”

“What are those?” Todd asked, pointing at the bulging cardboard cartons under the stairs.

“Ah, they’re no good,” Foxy said. “True war stories, mostly. Boring.”

“Can I look at some?”

“Sure. I’ll find the comics.”

But by the time fat Foxy Pegler found them, Todd no longer wanted to read comics. He was lost. Utterly lost.

It’s like a key turning in a lock. Or falling in love for the first time.

It had been like that. He had known about the war, of course—not the stupid one going on now, where the Americans had gotten the shit kicked out of them by a bunch of gooks in black pajamas—but World War II. He knew that the Americans wore round helmets with net on them and the krauts wore sort of square ones. He knew that the Americans won most of the battles and that the Germans had invented rockets near the end and shot them from Germany onto London. He had even known something about the concentration camps.

The difference between all of that and what he found in the magazines under the stairs in Foxy’s garage was like the difference between being told about germs and then actually seeing them in a microscope, squirming around and alive.

Here was Ilse Koch. Here were crematoriums with their doors standing open on their soot-clotted hinges. Here were officers in SS uniforms and prisoners in striped uniforms. The smell of the old pulp magazines was like the smell of the brush-fires burning out of control on the east of Santo Donato, and he could feel the old paper crumbling against the pads of his fingers, and he turned the pages, no longer in Foxy’s garage but caught somewhere crosswise in time, trying to cope with the idea that they had really done those things, that somebody had really done those things, and that somebody had let them do those things, and his head began to ache with a mixture of revulsion and excitement, and his eyes were hot and strained, but he read on, and from a column of print beneath a picture of tangled bodies at a place called Dachau, this figure jumped out at him:

6,000,000.

And he thought: Somebody goofed there, somebody added a zero or two, that’s twice as many people as there are in L.A.! But then, in another magazine (the cover of this one showed a woman chained to a wall while a guy in a Nazi uniform approached her with a poker in his hand and a grin on his face), he saw it again:

6,000,000.

His headache got worse. His mouth went dry. Dimly, from some distance, he heard Foxy saying he had to go in for supper. Todd asked Foxy if he could stay here in the garage and read while Foxy ate. Foxy gave him a look of mild puzzlement, shrugged, and said sure. And Todd read, hunched over the boxes of the old true war magazines, until his mother called and asked if he was ever going to go home.

Like a key turning in a lock.

All the magazines said it was bad, what had happened. But all the stories were continued at the back of the book, and when you turned to those pages, the words saying it was bad were surrounded by ads, and these ads sold German knives and belts and helmets as well as Magic Trusses and Guaranteed Hair Restorer. These ads sold German flags emblazoned with swastikas and Nazi Lugers and a game called Panzer Attack as well as correspondence lessons and offers to make you rich selling elevator shoes to short men. They said it was bad, but it seemed like a lot of people must not mind.

Like falling in love.

Oh yes, he remembered that day very well. He remembered everything about it—a yellowing pin-up calendar for a defunct year on the back wall, the oil-stain on the cement floor, the way the magazines had been tied together with orange twine. He remembered how his headache had gotten a little worse each time he thought of that incredible number,

6,000,000.

He remembered thinking: I want to know about everything that happened in those places. Everything. And I want to know which is more true—the words, or the ads they put beside the words.

He remembered Bugs Anderson as he at last pushed the boxes back under the stairs and thought: She was right. I’ve found my GREAT INTEREST.

• • •

Dussander looked at Todd for a long time. Then he crossed the living room and sat down heavily in a rocking chair. He looked at Todd again, unable to analyze the slightly dreamy, slightly nostalgic expression on the boy’s face.

“Yeah. It was the magazines that got me interested, but I figured a lot of what they said was just, you know, bullspit. So I went to the library and found out a lot more stuff. Some of it was even neater. At first the crummy librarian didn’t want me to look at any of it because it was in the adult section of the library, but I told her it was for school. If it’s for school they have to let you have it. She called my dad, though.” Todd’s eyes turned up scornfully. “Like she thought Dad didn’t know what I was doing, if you can dig that.”

“He did know?”

“Sure. My dad thinks kids should find out about life as soon as they can—the bad as well as the good. Then they’ll be ready for it. He says life is a tiger you have to grab by the tail, and if you don’t know the nature of the beast it will eat you up.”

“Mmmm,” Dussander said.

“My mom thinks the same way.”

“Mmmmm.” Dussander looked dazed, not quite sure where he was.

“Anyhow,” Todd said, “the library stuff was real good. They must have had a hundred books with stuff in them about the Nazi concentration camps, just here in the Santo Donato library. A lot of people must like to read about that stuff. There weren’t as many pictures as in Foxy’s dad’s magazines, but the other stuff was real gooshy. Chairs with spikes sticking up through the seats. Pulling out gold teeth with pliers. Poison gas that came out of the showers.” Todd shook his head. “You guys just went overboard, you know that? You really did.”

“Gooshy,” Dussander said heavily.

“I really did do a research paper, and you know what I got on it? An A-plus. Of course I had to be careful. You have to write that stuff in a certain way. You got to be careful.”

“Do you?” Dussander asked. He took another cigarette with a hand that trembled.

“Oh yeah. All those library books, they read a certain way. Like the guys who wrote them got puking sick over what they were writing about.” Todd was frowning, wrestling with the thought, trying to bring it out. The fact that tone, as that word is applied to writing, wasn’t yet in his vocabulary, made it more difficult. “They all write like they lost a lot of sleep over it. How we’ve got to be careful so nothing like that ever happens again. I made my paper like that, and I guess the teacher gave me an A just cause I read the source material without losing my lunch.” Once more, Todd smiled winningly.

Dussander dragged heavily on his unfiltered Kool. The tip trembled slightly. As he feathered smoke out of his nostrils, he coughed an old man’s dank, hollow cough. “I can hardly believe this conversation is taking place,” he said. He leaned forward and peered closely at Todd. “Boy, do you know the word ‘existentialism’?”

Todd ignored the question. “Did you ever meet Ilse Koch?”

“Ilse Koch?” Almost inaudibly, Dussander said: “Yes, I met her.”

“Was she beautiful?” Todd asked eagerly. “I mean . . .” His hands described an hourglass in the air.

“Surely you have seen her photograph?” Dussander asked. “An aficionado such as yourself?”

“What’s an af . . . aff . . .”

“An aficionado,” Dussander said, “is one who grooves. One who . . . gets off on something.”

“Yeah? Cool.” Todd’s grin, puzzled and weak for a moment, shone out triumphantly again. “Sure, I’ve seen her picture. But you know how they are in those books.” He spoke as if Dussander had them all. “Black and white, fuzzy . . . just snapshots. None of those guys knew they were taking pictures for, you know, history. Was she really stacked?”

“She was fat and dumpy and she had bad skin,” Dussander said shortly. He crushed his cigarette out half-smoked in a Table Talk pie-dish filled with dead butts.

“Oh. Golly.” Todd’s face fell.

“Just luck,” Dussander mused, looking at Todd. “You saw my picture in a war-adventures magazine and happened to ride next to me on the bus. Tcha!” He brought a fist down on the arm of his chair, but without much force.

“No sir, Mr. Dussander. There was more to it than that. A lot,” Todd added earnestly, leaning forward.

“Oh? Really?” The bushy eyebrows rose, signalling polite disbelief.

“Sure. I mean, the pictures of you in my scrapbook were all thirty years old, at least. I mean, it is 1974.”

“You keep a . . . a scrapbook?”

“Oh, yes, sir! It’s a good one. Hundreds of pictures. I’ll show it to you sometime. You’ll go ape.”

Dussander’s face pulled into a revolted grimace, but he said nothing.

“The first couple of times I saw you, I wasn’t sure at all. And then you got on the bus one day when it was raining, and you had this shiny black slicker on—”

“That,” Dussander breathed.

“Sure. There was a picture of you in a coat like that in one of the magazines out in Foxy’s garage. Also, a photo of you in your SS greatcoat in one of the library books. And when I saw you that day, I just said to myself, ‘It’s for sure. That’s Kurt Dussander.’ So I started to shadow you—”

“You did what?”

“Shadow you. Follow you. My ambition is to be a private detective like Sam Spade in the books, or Mannix on TV. Anyway, I was super careful. I didn’t want you to get wise. Want to look at some pictures?”

Todd took a folded-over manila envelope from his back pocket. Sweat had stuck the flap down. He peeled it back carefully. His eyes were sparkling like a boy thinking about his birthday, or Christmas, or the firecrackers he will shoot off on the Fourth of July.

“You took pictures of me?”

“Oh, you bet. I got this little camera. A Kodak. It’s thin and flat and fits right into your hand. Once you get the hang of it, you can take pictures of the subject just by holding the camera in your hand and spreading your fingers enough to let the lens peek through. Then you hit the button with your thumb.” Todd laughed modestly. “I got the hang of it, but I took a lot of pictures of my fingers while I did. I hung right in there, though. I think a person can do anything if they try hard enough, you know it? It’s corny but true.”

Kurt Dussander had begun to look white and ill, shrunken inside his robe. “Did you have these pictures finished by a commercial developer, boy?”

“Huh?” Todd looked shocked and startled, then contemptuous. “No! What do you think I am, stupid? My dad’s got a darkroom. I’ve been developing my own pictures since I was nine.”

Dussander said nothing, but he relaxed a little and some color came back into his face.

Todd handed him several glossy prints, the rough edges confirming that they had been home-developed. Dussander went through them, silently grim. Here he was sitting erect in a window seat of the downtown bus, with a copy of the latest James Michener, Centennial, in his hands. Here he was at the Devon Avenue bus stop, his umbrella under his arm and his head cocked back at an angle which suggested De Gaulle at his most imperial. Here he was standing on line just under the marquee of the Majestic Theater, erect and silent, conspicuous among the leaning teenagers and blank-faced housewives in curlers by his height and his bearing. Finally, here he was peering into his own mailbox.

“I was scared you might see me on that one,” Todd said. “It was a calculated risk. I was right across the street. Boy oh boy, I wish I could afford a Minolta with a telephoto lens. Someday . . .” Todd looked wistful.

“No doubt you had a story ready, just in case.”

“I was going to ask you if you’d seen my dog. Anyway, after I developed the pix, I compared them to these.”

He handed Dussander three Xeroxed photographs. He had seen them all before, many times. The first showed him in his office at the Patin resettlement camp; it had been cropped so nothing showed but him and the Nazi flag on its stand by his desk. The second was a picture that had been taken on the day of his enlistment. The last showed him shaking hands with Heinrich Gluecks, who had been subordinate only to Himmler himself.

“I was pretty sure then, but I couldn’t see if you had the harelip because of your goshdamn moustache. But I had to be sure, so I got this.”

He handed over the last sheet from his envelope. It had been folded over many times. Dirt was grimed into the creases. The corners were lopped and milled—the way papers get when they spend a long time in the pockets of young boys who have no shortage of things to do and places to go. It was a copy of the Israeli want-sheet on Kurt Dussander. Holding it in his hands, Dussander reflected on corpses that were unquiet and refused to stay buried.

“I took your fingerprints,” Todd said, smiling. “And then I did the compares to the one on the sheet.”

Dussander gaped at him and then uttered the German word for shit. “You did not!”

“Sure I did. My mom and dad gave me a fingerprint set for Christmas last year. A real one, not just a toy. It had the powder and three brushes for three different surfaces and special paper for lifting them. My folks know I want to be a PI when I grow up. Of course, they think I’ll grow out of it.” He dismissed this idea with a disinterested lift and drop of his shoulders. “The book explained all about whorls and lands and points of similarity. They’re called compares. You need eight compares for a fingerprint to get accepted in court.

“So anyway, one day when you were at the movies, I came here and dusted your mailbox and doorknob and lifted all the prints I could. Pretty smart, huh?”

Dussander said nothing. He was clutching the arms of his chair, and his toothless, deflated mouth was trembling. Todd didn’t like that. It made him look like he was on the verge of tears. That, of course, was ridiculous. The Blood-Fiend of Patin in tears? You might as well expect Chevrolet to go bankrupt or McDonald’s to give up burgers and start selling caviar and truffles.

“I got two sets of prints,” Todd said. “One of them didn’t look anything like the ones on the wanted poster. I figured those were the postman’s. The rest were yours. I found more than eight compares. I found fourteen good ones.” He grinned. “And that’s how I did it.”

“You are a little bastard,” Dussander said, and for a moment his eyes shone dangerously. Todd felt a tingling little thrill, as he had in the hall. Then Dussander slumped back again.

“Whom have you told?”

“No one.”

“Not even this friend? This Cony Pegler?”

“Foxy. Foxy Pegler. Nah, he’s a blabbermouth. I haven’t told anybody. There’s nobody I trust that much.”

“What do you want? Money? There is none, I’m afraid. In South America there was, although it was nothing as romantic or dangerous as the drug trade. There is—there was—a kind of ‘old boy network’ in Brazil and Paraguay and Santo Domingo. Fugitives from the war. I became part of their circle and did modestly well in minerals and ores—tin, copper, bauxite. Then the changes came. Nationalism, anti-Americanism. I might have ridden out the changes, but then Wiesenthal’s men caught my scent. Bad luck follows bad luck, boy, like dogs after a bitch in heat. Twice they almost had me; once I heard the Jew-bastards in the next room.

“They hanged Eichmann,” he whispered. One hand went to his neck, and his eyes had become as round as the eyes of a child listening to the darkest passage of a scary tale—“Hansel and Gretel,” perhaps, or “Bluebeard.” “He was an old man, of no danger to anyone. He was apolitical. Still, they hanged him.”

Todd nodded.

“At last, I went to the only people who could help me. They had helped others, and I could run no more.”

“You went to the Odessa?” Todd asked eagerly.

‘To the Sicilians,” Dussander said dryly, and Todd’s face fell again. “It was arranged. False papers, false past. Would you care for a drink, boy?”

“Sure. You got a Coke?”

“No Coke.” He pronounced it Kök.

“Milk?”

“Milk.” Dussander went through the archway and into the kitchen. A fluorescent bar buzzed into life. “I live now on stock dividends,” his voice came back. “Stocks I picked up after the war under yet another name. Through a bank in the State of Maine, if you please. The banker who bought them for me went to jail for murdering his wife a year after I bought them . . . life is sometimes strange, boy, hein?”

A refrigerator door opened and closed.

“The Sicilian jackals didn’t know about those stocks,” he said. “Today the Sicilians are everywhere, but in those days, Boston was as far north as they could be found. If they had known, they would have had those as well. They would have picked me clean and sent me to America to starve on welfare and food stamps.”

Todd heard a cupboard door opened; he heard liquid poured into a glass.

“A little General Motors, a little American Telephone and Telegraph, a hundred and fifty shares of Revlon. All this banker’s choices. Dufresne, his name was—I remember, because it sounds a little like mine. It seems he was not so smart at wife-killing as he was at picking growth stocks. The crime passionel, boy. It only proves that all men are donkeys who can read.”

He came back into the room, slippers whispering. He held two green plastic glasses that looked like the premiums they sometimes gave out at gas station openings. When you filled your tank, you got a free glass. Dussander thrust a glass at Todd.

“I lived adequately on the stock portfolio this Dufresne had set up for me for the first five years I was here. But then I sold my Diamond Match stock in order to buy this house and a small cottage not far from Big Sur. Then, inflation. Recession. I sold the cottage and one by one I sold the stocks, many of them at fantastic profits. I wish to God I had bought more. But I thought I was well-protected in other directions; the stocks were, as you Americans say, a ‘flier . . .’?” He made a toothless hissing sound and snapped his fingers.

Todd was bored. He had not come here to listen to Dussander whine about his money or mutter about his stocks. The thought of blackmailing Dussander had never even crossed Todd’s mind. Money? What would he do with it? He had his allowance; he had his paper route. If his monetary needs went higher than what these could provide during any given week, there was always someone who needed his lawn mowed.

Todd lifted his milk to his lips and then hesitated. His smile shone out again . . . an admiring smile. He extended the gas station premium glass to Dussander.

“You have some of it,” he said slyly.

Dussander stared at him for a moment, uncomprehending, and then rolled his bloodshot eyes. “Grüss Gott!” He took the glass, swallowed twice, and handed it back. “No gasping for breath. No clawing at the t’roat. No smell of bitter almonds. It is milk, boy. Milk. From the Dairylea Farms. On the carton is a picture of a smiling cow.”

Todd watched him warily for a moment, then took a small sip. Yes, it tasted like milk, sure did, but somehow he didn’t feel very thirsty anymore. He put the glass down. Dussander shrugged, raised his own glass, and took a swallow. He smacked his lips over it.

“Schnaps?” Todd asked.

“Bourbon. Ancient Age. Very nice. And cheap.”

Todd fiddled his fingers along the seams of his jeans.

“So,” Dussander said, “if you have decided to have a ‘flier’ of your own, you should be aware that you have picked a worthless stock.”

“Huh?”

“Blackmail,” Dussander said. “Isn’t that what they call it on Mannix and Hawaii Five-0 and Barnaby Jones? Extortion. If that was what—”

But Todd was laughing—hearty, boyish laughter. He shook his head, tried to speak, could not, and went on laughing.

“No,” Dussander said, and suddenly he looked gray and more frightened than he had since he and Todd had begun to speak. He took another large swallow of his drink, grimaced, and shuddered. “I see that is not it . . . at least, not the extortion of money. But, though you laugh, I smell extortion in it somewhere. What is it? Why do you come here and disturb an old man? Perhaps, as you say, I was once a Nazi. SS, even. Now I am only old, and to have a bowel movement I have to use a suppository. So what do you want?”

Todd had sobered again. He stared at Dussander with an open and appealing frankness. “Why . . . I want to hear about it. That’s all. That’s all I want. Really.”

“Hear about it?” Dussander echoed. He looked utterly perplexed.

Todd leaned forward, tanned elbows on bluejeaned knees. “Sure. The firing squads. The gas chambers. The ovens. The guys who had to dig their own graves and then stand on the ends so they’d fall into them. The . . .” His tongue came out and wetted his lips. “The examinations. The experiments. Everything. All the gooshy stuff.”

Dussander stared at him with a certain amazed detachment, the way a veterinarian might stare at a cat who was giving birth to a succession of two-headed kittens. “You are a monster,” he said softly.

Todd sniffed. “According to the books I read for my report, you’re the monster, Mr. Dussander. Not me. You sent them to the ovens, not me. Two thousand a day at Patin before you came, three thousand after, thirty-five hundred before the Russians came and made you stop. Himmler called you an efficiency expert and gave you a medal. So you call me a monster. Oh boy.”

“All of that is a filthy American lie,” Dussander said, stung. He set his glass down with a bang, slopping bourbon onto his hand and the table. “The problem was not of my making, nor was the solution. I was given orders and directives, which I followed.”

Todd’s smile widened; it was now almost a smirk.

“Oh, I know how the Americans have distorted that,” Dussander muttered. “But your own politicians make our Dr. Goebbels look like a child playing with picture books in a kindergarten. They speak of morality while they douse screaming children and old women in burning napalm. Your draft-resisters are called cowards and ‘peaceniks.’ For refusing to follow orders they are either put in jails or scourged from the country. Those who demonstrate against this country’s unfortunate Asian adventure are clubbed down in the streets. The GI soldiers who kill the innocent are decorated by Presidents, welcomed home from the bayoneting of children and the burning of hospitals with parades and bunting. They are given dinners, Keys to the City, free tickets to pro football games.” He toasted his glass in Todd’s direction. “Only those who lose are tried as war criminals for following orders and directives.” He drank and then had a coughing fit that brought thin color to his cheeks.

Through most of this Todd fidgeted the way he did when his parents discussed whatever had been on the news that night—good old Walter Klondike, his dad called him. He didn’t care about Dussander’s politics any more than he cared about Dussander’s stocks. His idea was that people made up politics so they could do things. Like when he wanted to feel around under Sharon Ackerman’s dress last year. Sharon said it was bad for him to want to do that, even though he could tell from her tone of voice that the idea sort of excited her. So he told her he wanted to be a doctor when he grew up and then she let him. That was politics. He wanted to hear about German doctors trying to mate women with dogs, putting identical twins into refrigerators to see whether they would die at the same time or if one of them would last longer, and electroshock therapy, and operations without anesthetic, and German soldiers raping all the women they wanted. The rest was just so much tired bullspit to cover up the gooshy stuff after someone came along and put a stop to it.

“If I hadn’t followed orders, I would have been dead.” Dussander was breathing hard, his upper body rocking back and forth in the chair, making the springs squeak. A little cloud of liquor-smell hung around him. “There was always the Russian front, nicht wahr? Our leaders were madmen, granted, but does one argue with madmen . . . especially when the maddest of them all has the luck of Satan. He escaped a brilliant assassination attempt by inches. Those who conspired were strangled with piano-wire, strangled slowly. Their death-agonies were filmed for the edification of the elite—”

“Yeah! Neat!” Todd cried impulsively. “Did you see that movie?”

“Yes. I saw. We all saw what happened to those unwilling or unable to run before the wind and wait for the storm to end. What we did then was the right thing. For that time and that place, it was the right thing. I would do it again. But . . .”

His eyes dropped to his glass. It was empty.

“. . . but I don’t wish to speak of it, or even think of it. What we did was motivated only by survival, and nothing about survival is pretty. I had dreams . . .” He slowly took a cigarette from the box on the TV. “Yes. For years I had them. Blackness, and sounds in the blackness. Tractor engines. Bulldozer engines. Gunbutts thudding against what might have been frozen earth, or human skulls. Whistles, sirens, pistol-shots, screams. The doors of cattle-cars rumbling open on cold winter afternoons.

“Then, in my dreams, all sounds would stop—and eyes would open in the dark, gleaming like the eyes of animals in a rainforest. For many years I lived on the edge of the jungle, and I suppose that is why it is always the jungle I smelled and felt in those dreams. When I woke from them I would be drenched with sweat, my heart thundering in my chest, my hand stuffed into my mouth to stifle the screams. And I would think: The dream is the truth. Brazil, Paraguay, Cuba . . . those places are the dream. In the reality I am still at Patin. The Russians are closer today than yesterday. Some of them are remembering that in 1943 they had to eat frozen German corpses to stay alive. Now they long to drink hot German blood. There were rumors, boy, that some of them did just that when they crossed into Germany: cut the t’roats of some prisoners and drank their blood out of a boot. I would wake up and think: The work must go on, if only so there is no evidence of what we did here, or so little that the world, which doesn’t want to believe it, won’t have to. I would think: The work must go on if we are to survive.”

Todd listened to this with close attention and great interest. This was pretty good, but he was sure there would be better stuff in the days ahead. All Dussander needed was a little prodding. Heck, he was lucky. Lots of men his age were senile.

Dussander dragged deeply on his cigarette. “Later, after the dreams went away, there were days when I would think I had seen someone from Patin. Never guards or fellow officers, always inmates. I remember one afternoon in West Germany, ten years ago. There was an accident on the Autobahn. Traffic was frozen in every lane. I sat in my Morris, listening to the radio, waiting for the traffic to move. I looked to my right. There was a very old Simca in the next lane, and the man behind the wheel was looking at me. He was perhaps fifty, and he looked ill. There was a scar on his cheek. His hair was white, short, cut badly. I looked away. The minutes passed and still the traffic didn’t move. I began snatching glances at the man in the Simca. Every time I did, he was looking at me, his face as still as death, his eyes sunken in their sockets. I became convinced he had been at Patin. He had been there and he had recognized me.”

Dussander wiped a hand across his eyes.

“It was winter. The man was wearing an overcoat. But I was convinced that if I got out of my car and went to him, made him take off his coat and push up his shirtsleeves, I would see the number on his arm.

“At last the traffic began to move again. I pulled away from the Simca. If the jam had lasted another ten minutes, I believe I would have gotten out of my car and pulled the old man out of his. I would have beaten him, number or no number. I would have beaten him for looking at me that way.

“Shortly after that, I left Germany forever.”

“Lucky for you,” Todd said.

Dussander shrugged. “It was the same everywhere. Havana, Mexico City, Rome. I was in Rome for three years, you know. I would see a man looking at me over his cappucino in a café . . . a woman in a hotel lobby who seemed more interested in me than in her magazine . . . a waiter in a restaurant who would keep glancing at me no matter whom he was serving. I would become convinced that these people were studying me, and that night the dream would come—the sounds, the jungle, the eyes.

“But when I came to America I put it out of my mind. I go to movies. I eat out once a week, always at one of those fast-food places that are so clean and so well-lighted by fluorescent bars. Here at my house I do jigsaw puzzles and I read novels—most of them bad ones—and watch TV. At night I drink until I’m sleepy. The dreams don’t come anymore. When I see someone looking at me in the supermarket or the library or the tobacconist’s, I think it must be because I look like their grandfather . . . or an old teacher . . . or a neighbor in a town they left some years ago.” He shook his head at Todd. “Whatever happened at Patin, it happened to another man. Not to me.”

“Great!” Todd said. “I want to hear all about it.”

Dussander’s eyes squeezed closed, and then opened slowly. “You don’t understand. I do not wish to speak of it.”

“You will, though. If you don’t, I’ll tell everyone who you are.”

Dussander stared at him, gray-faced. “I knew,” he said, “that I would find the extortion sooner or later.”

“Today I want to hear about the gas ovens,” Todd said. “How you baked them after they were dead.” His smile beamed out, rich and radiant. “But put your teeth in before you start. You look better with your teeth in.”

Dussander did as he was told. He talked to Todd about the gas ovens until Todd had to go home for lunch. Every time he tried to slip over into generalities, Todd would frown severely and ask him specific questions to get him back on the track. Dussander drank a great deal as he talked. He didn’t smile. Todd smiled. Todd smiled enough for both of them.

He looked like the total all-American kid as he pedaled his twenty-six-inch Schwinn with the apehanger handlebars up the residential suburban street, and that’s just what he was: Todd Bowden, thirteen years old, five-feet-eight and a healthy one hundred and forty pounds, hair the color of ripe corn, blue eyes, white even teeth, lightly tanned skin marred by not even the first shadow of adolescent acne.

He was smiling a summer vacation smile as he pedaled through the sun and shade not too far from his own house. He looked like the kind of kid who might have a paper route, and as a matter of fact, he did—he delivered the Santo Donato Clarion. He also looked like the kind of kid who might sell greeting cards for premiums, and he had done that, too. They were the kind that come with your name printed inside—JACK AND MARY BURKE, OR DON AND SALLY, OR THE MURCHISONS. He looked like the sort of boy who might whistle while he worked, and he often did so. He whistled quite prettily, in fact. His dad was an architectural engineer who made forty thousand dollars a year. His mom had majored in French in college and had met Todd’s father when he desperately needed a tutor. She typed manuscripts in her spare time. She had kept all of Todd’s old school report cards in a folder. Her favorite was his final fourth-grade card, on which Mrs. Upshaw had scratched: “Todd is an extremely apt pupil.” He was, too. Straight A’s and B’s all the way up the line. If he’d done any better—straight A’s, for example—his friends might have begun to think he was weird.

Now he brought his bike to a halt in front of 963 Claremont Street and stepped off it. The house was a small bungalow set discreetly back on its lot. It was white with green shutters and green trim. A hedge ran around the front. The hedge was well-watered and well-clipped.

Todd brushed his blonde hair out of his eyes and walked the Schwinn up the cement path to the steps. He was still smiling, and his smile was open and expectant and beautiful. He pushed down the bike’s kickstand with the toe of one Nike running-shoe and then picked the folded newspaper off the bottom step. It wasn’t the Clarion; it was the LA. Times. He put it under his arm and mounted the steps. At the top was a heavy wooden door with no window inside of a latched screen door. There was a doorbell on the right-hand doorframe, and below the bell were two small signs, each neatly screwed into the wood and covered with protective plastic so they wouldn’t yellow or waterspot. German efficiency, Todd thought, and his smile widened a little. It was an adult thought, and he always mentally congratulated himself when he had one of those.

The top sign said ARTHUR DENKER.

The bottom one said NO SOLICITORS, NO PEDDLERS, NO SALESMEN.

Smiling still, Todd rang the bell.

He could barely hear its muted burring, somewhere far off inside the small house. He took his finger off the bell and cocked his head a little, listening for footsteps. There were none. He looked at his Timex watch (one of the premiums he had gotten for selling personalized greeting cards) and saw that it was twelve past ten. The guy should be up by now. Todd himself was always up by seven-thirty at the latest, even during summer vacation. The early bird catches the worm.

He listened for another thirty seconds and when the house remained silent he leaned on the bell, watching the sweep second hand on his Timex as he did so. He had been pressing the doorbell for exactly seventy-one seconds when he finally heard shuffling footsteps. Slippers, he deduced from the soft wish-wish sound. Todd was into deductions. His current ambition was to become a private detective when he grew up.

“All right! All right!” the man who was pretending to be Arthur Denker called querulously. “I’m coming! Let it go! I’m coming!”

Todd stopped pushing the doorbell button.

A chain and bolt rattled on the far side of the windowless inner door. Then it was pulled open.

An old man, hunched inside a bathrobe, stood looking out through the screen. A cigarette smouldered between his fingers. Todd thought the man looked like a cross between Albert Einstein and Boris Karloff. His hair was long and white but beginning to yellow in an unpleasant way that was more nicotine than ivory. His face was wrinkled and pouched and puffy with sleep, and Todd saw with some distaste that he hadn’t bothered shaving for the last couple of days. Todd’s father was fond of saying, “A shave puts a shine on the morning.” Todd’s father shaved every day, whether he had to work or not.

The eyes looking out at Todd were watchful but deeply sunken, laced with snaps of red. Todd felt an instant of deep disappointment. The guy did look a little bit like Albert Einstein, and he did look a little bit like Boris Karloff, but what he looked like more than anything else was one of the seedy old winos that hung around down by the railroad yard.

But of course, Todd reminded himself, the man had just gotten up. Todd had seen Denker many times before today (although he had been very careful to make sure that Denker hadn’t seen him, no way, Jose), and on his public occasions, Denker looked very natty, every inch an officer in retirement, you might say, even though he was seventy-six if the articles Todd had read at the library had his birth-date right. On the days when Todd had shadowed him to the Shoprite where Denker did his shopping or to one of the three movie theaters on the bus line—Denker had no car—he was always dressed in one of three neatly kept suits, no matter how warm the weather. If the weather looked threatening he carried a furled umbrella under one arm like a swagger stick. He sometimes wore a trilby hat. And on the occasions when Denker went out, he was always neatly shaved and his white moustache (worn to conceal an imperfectly corrected harelip) was carefully trimmed.

“A boy,” he said now. His voice was thick and sleepy. Todd saw with new disappointment that his robe was faded and tacky. One rounded collar point stood up at a drunken angle to poke at his wattled neck. There was a splotch of something that might have been chili or possibly A-l Steak Sauce on the left lapel, and he smelled of cigarettes and stale booze.

“A boy,” he repeated. “I don’t need anything, boy. Read the sign. You can read, can’t you? Of course you can. All American boys can read. Don’t be a nuisance, boy. Good day.”

The door began to close.

He might have dropped it right there, Todd thought much later on one of the nights when sleep was hard to find. His disappointment at seeing the man for the first time at close range, seeing him with his street-face put away—hanging in the closet, you might say, along with his umbrella and his trilby—might have done it. It could have ended in that moment, the tiny, unimportant snicking sound of the latch cutting off everything that happened later as neatly as a pair of shears. But, as the man himself had observed, he was an American boy, and he had been taught that persistence is a virtue.

“Don’t forget your paper, Mr. Dussander,” Todd said, holding the Times out politely.

The door stopped dead in its swing, still inches from the jamb. A tight and watchful expression flitted across Kurt Dussander’s face and was gone at once. There might have been fear in that expression. It was good, the way he had made that expression disappear, but Todd was disappointed for the third time. He hadn’t expected Dussander to be good; he had expected Dussander to be great.

Boy, Todd thought with real disgust. Boy oh boy.

He pulled the door open again. One hand, bunched with arthritis, unlatched the screen door. The hand pushed the screen door open just enough to wriggle through like a spider and close over the edge of the paper Todd was holding out. The boy saw with distaste that the old man’s fingernails were long and yellow and horny. It was a hand that had spent most of its waking hours holding one cigarette after another. Todd thought smoking was a filthy dangerous habit, one he himself would never take up. It really was a wonder that Dussander had lived as long as he had.

The old man tugged. “Give me my paper.”

“Sure thing, Mr. Dussander.” Todd released his hold on the paper. The spider-hand yanked it inside. The screen closed.

“My name is Denker,” the old man said. “Not this Doo-Zander. Apparently you cannot read. What a pity. Good day.”

The door started to close again. Todd spoke rapidly into the narrowing gap. “Bergen-Belsen, January 1943 to June 1943. Auschwitz, June 1943 to June of 1944, Unterkommandant. Patin—”

The door stopped again. The old man’s pouched and pallid face hung in the gap like a wrinkled, half-deflated balloon. Todd smiled.

“You left Patin just ahead of the Russians. You got to Buenos Aires. Some people say you got rich there, investing the gold you took out of Germany in the drug trade. Whatever, you were in Mexico City from 1950 to 1952. Then—”

“Boy, you are crazy like a cuckoo bird.” One of the arthritic fingers twirled circles around a misshapen ear. But the toothless mouth was quivering in an infirm, panicky way.

“From 1952 until 1958, I don’t know,” Todd said, smiling more widely still. “No one does, I guess, or at least they’re not telling. But an Israeli agent spotted you in Cuba, working as the concierge in a big hotel just before Castro took over. They lost you when the rebels came into Havana. You popped up in West Berlin in 1965. They almost got you.” He pronounced the last two words as one: gotcha. At the same time he squeezed all of his fingers together into one large, wriggling fist. Dussander’s eyes dropped to those well-made and well-nourished American hands, hands that were made for building soapbox racers and Aurora models. Todd had done both. In fact, the year before, he and his dad had built a model of the Titanic. It had taken almost four months, and Todd’s father kept it in his office.

“I don’t know what you are talking about,” Dussander said. Without his false teeth, his words had a mushy sound Todd didn’t like. It didn’t sound . . . well, authentic. Colonel Klink on Hogan’s Heroes sounded more like a Nazi than Dussander did. But in his time he must have been a real whiz. In an article on the death-camps in Men’s Action, the writer had called him The Blood-Fiend of Patin. “Get out of here, boy. Before I call the police.”

“Gee, I guess you better call them, Mr. Dussander. Or Herr Dussander, if you like that better.” He continued to smile, showing perfect teeth that had been fluoridated since the beginning of his life and bathed thrice a day in Crest toothpaste for almost as long. “After 1965, no one saw you again . . . until I did, two months ago, on the downtown bus.”

“You’re insane.”

“So if you want to call the police,” Todd said, smiling, “you go right ahead. I’ll wait on the stoop. But if you don’t want to call them right away, why don’t I come in? We’ll talk.”

There was a long moment while the old man looked at the smiling boy. Birds twitted in the trees. On the next block a power mower was running, and far off, on busier streets, horns honked out their own rhythm of life and commerce.

In spite of everything, Todd felt the onset of doubt. He couldn’t be wrong, could he? Was there some mistake on his part? He didn’t think so, but this was no schoolroom exercise. It was real life. So he felt a surge of relief (mild relief, he assured himself later) when Dussander said: “You may come in for a moment, if you like. But only because I do not wish to make trouble for you, you understand?”

“Sure, Mr. Dussander,” Todd said. He opened the screen and came into the hall. Dussander closed the door behind them, shutting off the morning.

The house smelled stale and slightly malty. It smelled the way Todd’s own house smelled sometimes the morning after his folks had thrown a party and before his mother had had a chance to air it out. But this smell was worse. It was lived-in and ground-in. It was liquor, fried food, sweat, old clothes, and some stinky medicinal smell like Vick’s or Mentholatum. It was dark in the hallway, and Dussander was standing too close, his head hunched into the collar of his robe like the head of a vulture waiting for some hurt animal to give up the ghost. In that instant, despite the stubble and the loosely hanging flesh, Todd could see the man who had stood inside the black SS uniform more clearly than he had ever seen him on the street. And he felt a sudden lancet of fear slide into his belly. Mild fear, he amended later.

“I should tell you that if anything happens to me—” he began, and then Dussander shuffled past him and into the living room, his slippers wish-wishing on the floor. He flapped a contemptuous hand at Todd, and Todd felt a flush of hot blood mount into his throat and cheeks.

Todd followed him, his smile wavering for the first time. He had not pictured it happening quite like this. But it would work out. Things would come into focus. Of course they would. Things always did. He began to smile again as he stepped into the living room.

It was another disappointment—and how!—but one he supposed he should have been prepared for. There was of course no oil portrait of Hitler with his forelock dangling and eyes that followed you. No medals in cases, no ceremonial sword mounted on the wall, no Luger or PPK Walther on the mantel (there was, in fact, no mantel). Of course, Todd told himself, the guy would have to be crazy to put any of those things out where people could see them. Still, it was hard to put everything you saw in the movies or on TV out of your head. It looked like the living room of any old man living alone on a slightly frayed pension. The fake fireplace was faced with fake bricks. A Westclox hung over it. There was a black and white Motorola TV on a stand; the tips of the rabbit ears had been wrapped in aluminum foil to improve reception. The floor was covered with a gray rug; its nap was balding. The magazine rack by the sofa held copies of National Geographic, Reader’s Digest, and the L.A. Times. Instead of Hitler or a ceremonial sword hung on the wall, there was a framed certificate of citizenship and a picture of a woman in a funny hat. Dussander later told him that sort of hat was called a cloche, and they had been popular in the twenties and thirties.

“My wife,” Dussander said sentimentally. “She died in 1955 of a lung disease. At that time I was working at the Menschler Motor Works in Essen. I was heartbroken.”

Todd continued to smile. He crossed the room as if to get a better look at the woman in the picture. Instead of looking at the picture, he fingered the shade on a small table-lamp.

“Stop that!” Dussander barked harshly. Todd jumped back a little.

“That was good,” he said sincerely. “Really commanding. It was Ilse Koch who had the lampshades made out of human skin, wasn’t it? And she was the one who had the trick with the little glass tubes.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Dussander said. There was a package of Kools, the kind with no filter, on top of the TV. He offered them to Todd. “Cigarette?” he asked, and grinned. His grin was hideous.

“No. They give you lung cancer. My dad used to smoke, but he gave it up. He went to Smokenders.”

“Did he.” Dussander produced a wooden match from the pocket of his robe and scratched it indifferently on the plastic case of the Motorola. Puffing, he said: “Can you give me one reason why I shouldn’t call the police and tell them of the monstrous accusations you’ve just made? One reason? Speak quickly, boy. The telephone is just down the hall. Your father would spank you, I think. You would sit for dinner on a cushion for a week or so, eh?”

“My parents don’t believe in spanking. Corporal punishment causes more problems than it cures.” Todd’s eyes suddenly gleamed. “Did you spank any of them? The women? Did you take off their clothes and—”

With a muffled exclamation, Dussander started for the phone.

Todd said coldly: “You better not do that.”

Dussander turned. In measured tones that were spoiled only slightly by the fact that his false teeth were not in, he said: “I tell you this once, boy, and once only. My name is Arthur Denker. It has never been anything else; it has not even been Americanized. I was in fact named Arthur by my father, who greatly admired the stories of Arthur Conan Doyle. It has never been Doo-Zander, or Himmler, or Father Christmas. I was a reserve lieutenant in the war. I never joined the Nazi party. In the battle of Berlin I fought for three weeks. I will admit that in the late thirties, when I was first married, I supported Hitler. He ended the depression and returned some of the pride we had lost in the aftermath of the sickening and unfair Treaty of Versailles. I suppose I supported him mostly because I got a job and there was tobacco again, and I didn’t need to hunt through the gutters when I needed to smoke. I thought, in the late thirties, that he was a great man. In his own way, perhaps he was. But at the end he was mad, directing phantom armies at the whim of an astrologer. He even gave Blondi, his dog, a death-capsule. The act of a madman; by the end they were all madmen, singing the ‘Horst Wessel Song’ as they fed poison to their children. On May 2nd, 1945, my regiment gave up to the Americans. I remember that a private soldier named Hackermeyer gave me a chocolate bar. I wept. There was no reason to fight on; the war was over, and really had been since February. I was interned at Essen and was treated very well. We listened to the Nuremberg trials on the radio, and when Goering committed suicide, I traded fourteen American cigarettes for half a bottle of Schnaps and got drunk. When I was released, I put wheels on cars at the Essen Motor Works until 1963, when I retired. Later I emigrated to the United States. To come here was a lifelong ambition. In 1967 I became a citizen. I am an American. I vote. No Buenos Aires. No drug dealing. No Berlin. No Cuba.” He pronounced it Koo-ba. “And now, unless you leave, I make my telephone call.”

He watched Todd do nothing. Then he went down the hall and picked up the telephone. Still Todd stood in the living room, beside the table with the small lamp on it.

Dussander began to dial. Todd watched him, his heart speeding up until it was drumming in his chest. After the fourth number, Dussander turned and looked at him. His shoulders sagged. He put the phone down.

“A boy,” he breathed, “A boy.”

Todd smiled widely but rather modestly.

“How did you find out?”

“One piece of luck and a lot of hard work,” Todd said. “There’s this friend of mine, Harold Pegler his name is, only all the kids call him Foxy. He plays second base for our team. His dad’s got all these magazines out in his garage. Great big stacks of them. War magazines. They’re old. I looked for some new ones, but the guy who runs the newsstand across from the school says most of them went out of business. In most of them there’s pictures of krauts—German soldiers, I mean—and Japs torturing these women. And articles about the concentration camps. I really groove on all that concentration camp stuff.”

“You . . . groove on it.” Dussander was staring at him, one hand rubbing up and down on his cheek, producing a very small sandpapery sound.

“Groove. You know. I get off on it. I’m interested.”

He remembered that day in Foxy’s garage as clearly as anything in his life—more clearly, he suspected. He remembered in the fifth grade, before Careers Day, how Mrs. Anderson (all the kids called her Bugs because of her big front teeth) had talked to them about what she called finding YOUR GREAT INTEREST.

“It comes all at once,” Bugs Anderson had rhapsodized. “You see something for the first time, and right away you know you have found YOUR GREAT INTEREST. It’s like a key turning in a lock. Or falling in love for the first time. That’s why Careers Day is so important, children—it may be the day on which you find YOUR GREAT INTEREST.” And she had gone on to tell them about her own GREAT INTEREST, which turned out not to be teaching the fifth grade but collecting nineteenth-century postcards.

Todd had thought Mrs. Anderson was full of bullspit at the time, but that day in Foxy’s garage, he remembered what she had said and wondered if maybe she hadn’t been right after all.

The Santa Anas had been blowing that day, and to the east there were brush-fires. He remembered the smell of burning, hot and greasy. He remembered Foxy’s crewcut, and the flakes of Butch Wax clinging to the front of it. He remembered everything.

“I know there’s comics here someplace,” Foxy had said. His mother had a hangover and had kicked them out of the house for making too much noise. “Neat ones. They’re Westerns, mostly, but there’s some Turok, Son of Stone and—”

“What are those?” Todd asked, pointing at the bulging cardboard cartons under the stairs.

“Ah, they’re no good,” Foxy said. “True war stories, mostly. Boring.”

“Can I look at some?”

“Sure. I’ll find the comics.”

But by the time fat Foxy Pegler found them, Todd no longer wanted to read comics. He was lost. Utterly lost.

It’s like a key turning in a lock. Or falling in love for the first time.

It had been like that. He had known about the war, of course—not the stupid one going on now, where the Americans had gotten the shit kicked out of them by a bunch of gooks in black pajamas—but World War II. He knew that the Americans wore round helmets with net on them and the krauts wore sort of square ones. He knew that the Americans won most of the battles and that the Germans had invented rockets near the end and shot them from Germany onto London. He had even known something about the concentration camps.

The difference between all of that and what he found in the magazines under the stairs in Foxy’s garage was like the difference between being told about germs and then actually seeing them in a microscope, squirming around and alive.

Here was Ilse Koch. Here were crematoriums with their doors standing open on their soot-clotted hinges. Here were officers in SS uniforms and prisoners in striped uniforms. The smell of the old pulp magazines was like the smell of the brush-fires burning out of control on the east of Santo Donato, and he could feel the old paper crumbling against the pads of his fingers, and he turned the pages, no longer in Foxy’s garage but caught somewhere crosswise in time, trying to cope with the idea that they had really done those things, that somebody had really done those things, and that somebody had let them do those things, and his head began to ache with a mixture of revulsion and excitement, and his eyes were hot and strained, but he read on, and from a column of print beneath a picture of tangled bodies at a place called Dachau, this figure jumped out at him:

6,000,000.

And he thought: Somebody goofed there, somebody added a zero or two, that’s twice as many people as there are in L.A.! But then, in another magazine (the cover of this one showed a woman chained to a wall while a guy in a Nazi uniform approached her with a poker in his hand and a grin on his face), he saw it again:

6,000,000.

His headache got worse. His mouth went dry. Dimly, from some distance, he heard Foxy saying he had to go in for supper. Todd asked Foxy if he could stay here in the garage and read while Foxy ate. Foxy gave him a look of mild puzzlement, shrugged, and said sure. And Todd read, hunched over the boxes of the old true war magazines, until his mother called and asked if he was ever going to go home.

Like a key turning in a lock.

All the magazines said it was bad, what had happened. But all the stories were continued at the back of the book, and when you turned to those pages, the words saying it was bad were surrounded by ads, and these ads sold German knives and belts and helmets as well as Magic Trusses and Guaranteed Hair Restorer. These ads sold German flags emblazoned with swastikas and Nazi Lugers and a game called Panzer Attack as well as correspondence lessons and offers to make you rich selling elevator shoes to short men. They said it was bad, but it seemed like a lot of people must not mind.

Like falling in love.

Oh yes, he remembered that day very well. He remembered everything about it—a yellowing pin-up calendar for a defunct year on the back wall, the oil-stain on the cement floor, the way the magazines had been tied together with orange twine. He remembered how his headache had gotten a little worse each time he thought of that incredible number,

6,000,000.

He remembered thinking: I want to know about everything that happened in those places. Everything. And I want to know which is more true—the words, or the ads they put beside the words.

He remembered Bugs Anderson as he at last pushed the boxes back under the stairs and thought: She was right. I’ve found my GREAT INTEREST.

• • •

Dussander looked at Todd for a long time. Then he crossed the living room and sat down heavily in a rocking chair. He looked at Todd again, unable to analyze the slightly dreamy, slightly nostalgic expression on the boy’s face.

“Yeah. It was the magazines that got me interested, but I figured a lot of what they said was just, you know, bullspit. So I went to the library and found out a lot more stuff. Some of it was even neater. At first the crummy librarian didn’t want me to look at any of it because it was in the adult section of the library, but I told her it was for school. If it’s for school they have to let you have it. She called my dad, though.” Todd’s eyes turned up scornfully. “Like she thought Dad didn’t know what I was doing, if you can dig that.”

“He did know?”