Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

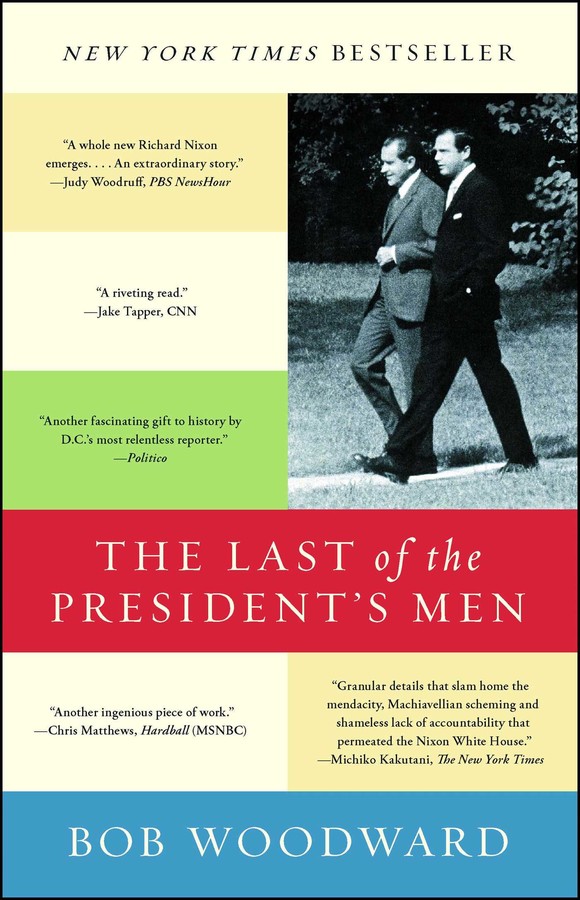

Bob Woodward exposes one of the final pieces of the Richard Nixon puzzle in this “intimate but disturbing portrayal of Nixon in the Oval Office” (The Washington Post).

“Four decades after Watergate shook America, journalist Bob Woodward returns to the scandal to profile Alexander Butterfield, the Richard Nixon aide who revealed the existence of the Oval Office tapes and effectively toppled the presidency…Woodward re-creates detailed scenes, which reveal the petty power plays of America’s most powerful men…a close-up view of the Oval Office in its darkest hour” (Kirkus Reviews). In The Last of the President’s Men, Woodward reveals the untold story based on forty-six hours of interviews with Butterfield, supported by thousands of documents—many of them original and not in the presidential archives and libraries—and uncovered new dimensions of Nixon’s secrets, obsessions, and deceptions.

“This volume…amplifies (rather than revises) the familiar, almost Miltonian portrait of the thirty-seventh president…as a brooding, duplicitous despot, obsessed with enemies and score-settling and not the least bit hesitant about lying to the public and breaking the law” (The New York Times). Today, The Last of the President’s Men could not be more timely and relevant as voters question how much do we know about those who are now seeking the presidency in 2016—what really drives them, how do they really make decisions, who do they surround themselves with, and what are their true political and personal values? This is “yet another fascinating gift to history by DC’s most relentless reporter” (Politico).

“Four decades after Watergate shook America, journalist Bob Woodward returns to the scandal to profile Alexander Butterfield, the Richard Nixon aide who revealed the existence of the Oval Office tapes and effectively toppled the presidency…Woodward re-creates detailed scenes, which reveal the petty power plays of America’s most powerful men…a close-up view of the Oval Office in its darkest hour” (Kirkus Reviews). In The Last of the President’s Men, Woodward reveals the untold story based on forty-six hours of interviews with Butterfield, supported by thousands of documents—many of them original and not in the presidential archives and libraries—and uncovered new dimensions of Nixon’s secrets, obsessions, and deceptions.

“This volume…amplifies (rather than revises) the familiar, almost Miltonian portrait of the thirty-seventh president…as a brooding, duplicitous despot, obsessed with enemies and score-settling and not the least bit hesitant about lying to the public and breaking the law” (The New York Times). Today, The Last of the President’s Men could not be more timely and relevant as voters question how much do we know about those who are now seeking the presidency in 2016—what really drives them, how do they really make decisions, who do they surround themselves with, and what are their true political and personal values? This is “yet another fascinating gift to history by DC’s most relentless reporter” (Politico).

Excerpt

The Last of the President’s Men 1

Colonel Butterfield was in a foul mood. The 42-year-old Air Force officer was on the path to four stars, and maybe the top uniformed job in the Air Force. “I was an ambitious son of a bitch,” he said later, “and I’d been lucky. I had a very good record. I was in this thing to go all the way . . . to be the chief of staff.”

He was, however, stuck in Australia as the senior U.S. military officer and representative of CINCPAC, the Commander in Chief Pacific—a reward for years in Vietnam and in the Office of the Secretary of Defense as liaison to the Lyndon Johnson White House. He had been promised he would only be in Australia for two years, but now they, the mysterious they, wanted to extend him another two years.

He saw it as a career disaster, keeping him out of the action, the “smoke” as he called it—the center of things. The “smoke” was Washington or Vietnam, where he had flown 98 combat reconnaissance missions.

On this particular day, November 20, 1968, he was in Port Moresby, New Guinea, the giant island in the Pacific, just north of Australia, traveling with the U.S. ambassador to Australia.

Butterfield picked up a copy of the Tok-Tok, the local newspaper. Here would be some intel on what was going on in the smoke. He took the paper back to his motel room and settled in with a sandwich. The main story was Richard Nixon, who had just won election as president 15 days earlier. Butterfield had voted for him.

He stopped cold. Nixon’s top aide was identified as H.R. “Bob” Haldeman. Was it possible? Haldeman was an old college acquaintance. It was astonishing that Haldeman was running the transition team preparing to take over the White House and the U.S. government.

Butterfield and Haldeman had known each other as students at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) in the mid-1940s. Their girlfriends, whom they each later married, were Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority sisters and close friends. The couples had double-dated. Haldeman was quiet, a somewhat colorless man, austere, not very political. He often came across as a bit of an asshole who was brusque with his girlfriend, Jo. Butterfield had lost touch with Haldeman but Jo and Butterfield’s wife, Charlotte, exchanged Christmas cards and snapshots of their children.

It wasn’t much to hang on to. But a fighter pilot knew about coincidence and chance, the quick maneuver in the air. It was the difference between ace or dead.

Haldeman! He tried to recall everything about him. How much could you learn from a double date and hanging around Fraternity Row? They had been in different fraternities. Haldeman was a Beta, which was considered the best. Old Harry Robbins, H.R. “Bob.” Butterfield needed an exit strategy and now he thought, “Here’s my out.” It was worth a try.

Butterfield had almost perfect Efficiency Reports, the formal evaluations that drive promotions. He had served as aide to two generals. With a gentle, relaxed charm he knew how to please the boss without fawning. He had earned early promotions, and his personnel file was stuffed with letters of commendation from top civilians at the Pentagon and from Vice President Hubert Humphrey. He looked the part of the classic Air Force officer. “He was drop-dead handsome,” said Charlotte in 2014, nearly 30 years after their divorce.

“If you’re going to get promoted to general officer,” Butterfield told me later, “you’ve got to be where the smoke is . . . in a really important, highly visible job in either Washington, D.C., or back in Vietnam. And command of a tactical fighter wing in Vietnam is what I wanted in the worst way.

“I was desperate to get back to Vietnam. If I have to be delayed [in Australia] for another two years, I’m dead in the water. I’m frantic, I’m actually frantic. I hate to admit that.” The urgency, he said, was simply because no one knew how long the war would last, and he did not want to miss out.

Butterfield awoke the next morning to heavy rain in New Guinea, and lay in bed thinking. If only he could talk with Haldeman, an unhurried session to tout his record: Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had employed him as a contact point in the White House. He had prepared McNamara’s regular military reports to the cabinet and accompanied him whenever he visited the White House. He knew a lot about power levers in Washington. He wanted to tell his UCLA pal about how crucial it was for him to be in an important, high-visibility assignment when he would became eligible for promotion to brigadier general, the one-star generalship, and the road to the smoke.

Would Haldeman understand? Could he possibly pull some strings? There were lots of strings to be pulled, especially from the vantage of the White House.

The weather stayed bad. Good. He wanted time. He grabbed the shuttle bus to the tiny airport terminal. Scanning the day-old paper from Sydney, he saw nothing about Nixon or his transition. Damn it! He thumbed through the other newspapers and several magazines. Nothing. At the counter, he sipped orange juice and coffee. The rain continued. Butterfield’s mind was churning hard. He bought an inexpensive bag of cookies and returned to the motel and hung the pidgin sign on the door: NO WAKIM MANISLIP (Do Not Disturb). Shedding his damp clothes, he put on a robe and sat to write. “Dear Bob . . .”

At first Butterfield wanted to describe his plight and see if Haldeman would intervene and assist with a new Air Force assignment. He wanted to get back to Vietnam with a wing command, a large unit of 75 or more planes. That seemed incredibly audacious. But Butterfield’s strong suit was personality. At UCLA he had been named the Most Collegiate Looking Male, and in high school the Most Popular. He had been class president twice in two different high schools, and student body president at the end of his junior year. He had earned letters and gold awards in football, basketball and track. Soon the letter to Haldeman was a direct appeal for a face-to-face meeting at the Pierre Hotel in New York, where the president-elect had set up his transition shop. Just 20 to 30 minutes. That was a bold request but Butterfield was a solid and respectable voice from the past.

He was running out of motel stationery, down to the last sheet. Going over to the bed, he lay down. What did he really want? Was it just an assist with a new assignment? Or was it more?

Butterfield imagined himself in an office talking to Haldeman. Would Bob still have that businesslike aura? The cold efficiency had doubtless appealed to Nixon. Butterfield knew the type from the Air Force. If he could get an audience, he would be able to establish a rapport. That was what he did, that was one of his talents. He knew that it was also dicey. If he went outside the chain of command to Haldeman, it could be seen as an impropriety. So he had to ask himself, What is my true objective? Why is it suddenly so important to put myself in front of Haldeman and try to impress him?

But in one of those rationalizations common to all and for which Butterfield forgave himself, he decided he could offer his professional services for a post on Nixon’s National Security Council staff. That would position him to return to Vietnam. That could be easy, he figured. He had to present himself as a clear-eyed colonel of excellent character and deportment. He was a graduate of the National War College, had a master’s degree in foreign affairs, had lived in six foreign countries. He pretty well knew the world and the issues. Not a bad package, he concluded. He was also combat ready and trained in every facet of tactical aviation—air-to-air, air-to-ground, air defense and reconnaissance. He was one of the few Air Force colonels with that range of experience. For two years, he also had been a member of the Air Force Skyblazers, America’s only formation aerobatic team in Europe.

Out of motel stationery, he went to the front desk and got more. Soon back in Australia, he revised his letter, making it into a biographical résumé, and sent it off. Later he tried to call Haldeman in New York. No luck.

Finally, Butterfield reached Larry Higby, Haldeman’s executive assistant, on the phone. Higby was Mr. Step-and-Fetch-It. (Later in the Nixon White House the staff assistants were called “Higbys.” Even Higby eventually had a Higby who was known as “Higby’s Higby.”)

“Colonel Butterfield, this is Larry Higby. Bob is busy now. Can I be helpful? Bob knows you’re calling and he told me you two knew each other at UCLA.”

Butterfield explained that he was coming to Washington on business. Of course the only business was to see Haldeman but he didn’t say that. He said he wanted no more than 30 minutes on an important personal matter. He knew he wasn’t fooling Higby, who replied they should talk the next day, and that he would probably have more to go on.

In Australia Butterfield was his own boss in charge of his schedule so he arranged to take leave and set up his travel. Within days he was in a room at the Washington Statler Hilton watching Nixon on television announce his cabinet.

Butterfield would later write in his memoir draft, “I took note of the Cabinet selectees’ names and as I did so a strange feeling came over me. It was one I’ve never forgotten—a good feeling, one of confidence, a premonition of sorts that I was closing in on my destiny, that I would definitely be a part of this upcoming Administration.”

The next morning, in freshly pressed uniform, Butterfield took a cab across the Potomac River to the Pentagon, which was familiar territory. He had worked there in several assignments. During the morning he tracked down colleagues who pulled the strings on the many military programs in Australia.

At noon he walked to the vast Pentagon Concourse, a mini-mall of retail stores, found a pay phone and called Higby.

“Mr. Higby is not available. Would you care to leave a message?”

Goddamnit! Butterfield muttered. He stared at the coin box of the pay phone, his long legs extended out of the booth. Now he was in the delicate minuet of making sure Haldeman knew he was available but not appearing overanxious. He calculated that if he called back in 30 minutes, and then again and again, his call slips could pile up and he would look like a pest. Not persistent, but annoying. Difficult and unwelcome. He decided to play a version of Hard to Get. He would wait until mid-afternoon to call again.

He went into D.C. and lunched alone at Duke Zeibert’s, then one of the most famous and busiest restaurants with the power set. He could think of many restaurants to have a belt—the Jockey Club, Rive Gauche, or Sans Souci. He’d dined and drunk in all of them. No city brought back more stirring memories because over the years he had been in and out of Washington, especially as the senior aide to General Rosy O’Donnell, who had been commander-in-chief of the Pacific Air Forces in the early 1960s.

At 3 p.m. he picked up the phone.

Bob will be able to see you tomorrow afternoon here in New York, Higby said. They agreed on 2 p.m.

The next day, Butterfield flew to New York City and checked his bags at the Plaza Hotel. As soon as the meeting with Haldeman was over, he was heading back to Australia. He then went down to the Oyster Bar for a light lunch and a little meditation—a comforting stream of hope punctuated with flashes of deep worry. He needed to present himself as a competent potential addition to Nixon’s team. There was much to think about. What exactly was the course he wanted to take? And was he going about it in the right way? How many acquaintances from decades back did Haldeman have knocking on his door? There was a bit of effrontery in it, but Haldeman also might find it comforting. The top aide to the president might be suspicious of new friends.

Butterfield stopped at the men’s room to gargle and brush his teeth, a ritual he practiced before important meetings. Soon he was out the door with briefcase in hand. It was cold but sunny, just right for the walk of several blocks to the Pierre, which had an elegance of its own. He visited the men’s room again to comb his hair. Whenever he went hatless, even in the slightest breeze, his wispy hair would go standing up on end. He was conscious of not wanting to look unkempt or goofy as though he had just stuck a finger in an electrical socket.

“I’m walking in for the final exam,” he recalled.

At the front desk, he asked for the main floor of the Nixon Transition Office and headed for the elevators.

Suddenly there was a commotion behind him, men moving fast. As he turned, he saw this wave sweeping in from the chilly air outside. He knew at once it was Secret Service moving with that special urgency and self-importance. “There’s this rush of humanity,” Butterfield recalled. “It looked like 40 or 50 people. Some of them had cameras. So this was the press. And lo and behold, Richard Nixon. I’d never laid eyes on Richard Nixon, but he comes rushing in. I’d thought at the time he looked a little more handsome than I thought he was, and a bit taller.”

Nixon smiled and nodded to the hotel staff and bystanders and did not turn Butterfield’s way. In 30 seconds Nixon and his Secret Service agents, and perhaps a handler or two, had crowded into an elevator and were gone.

Butterfield marveled at the way the old Haldeman connection was going, the timing, the prospect . . . the sense of destiny. In the back of his mind was the question: how far to push this? Well, he was pushing it to the limit, and the main event was to come. Maybe his hope was excessive, and he would get a polite brush-off, “Good to see you, Alex, and may the rest of your life turn out well.”

Colonel Butterfield was in a foul mood. The 42-year-old Air Force officer was on the path to four stars, and maybe the top uniformed job in the Air Force. “I was an ambitious son of a bitch,” he said later, “and I’d been lucky. I had a very good record. I was in this thing to go all the way . . . to be the chief of staff.”

He was, however, stuck in Australia as the senior U.S. military officer and representative of CINCPAC, the Commander in Chief Pacific—a reward for years in Vietnam and in the Office of the Secretary of Defense as liaison to the Lyndon Johnson White House. He had been promised he would only be in Australia for two years, but now they, the mysterious they, wanted to extend him another two years.

He saw it as a career disaster, keeping him out of the action, the “smoke” as he called it—the center of things. The “smoke” was Washington or Vietnam, where he had flown 98 combat reconnaissance missions.

On this particular day, November 20, 1968, he was in Port Moresby, New Guinea, the giant island in the Pacific, just north of Australia, traveling with the U.S. ambassador to Australia.

Butterfield picked up a copy of the Tok-Tok, the local newspaper. Here would be some intel on what was going on in the smoke. He took the paper back to his motel room and settled in with a sandwich. The main story was Richard Nixon, who had just won election as president 15 days earlier. Butterfield had voted for him.

He stopped cold. Nixon’s top aide was identified as H.R. “Bob” Haldeman. Was it possible? Haldeman was an old college acquaintance. It was astonishing that Haldeman was running the transition team preparing to take over the White House and the U.S. government.

Butterfield and Haldeman had known each other as students at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) in the mid-1940s. Their girlfriends, whom they each later married, were Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority sisters and close friends. The couples had double-dated. Haldeman was quiet, a somewhat colorless man, austere, not very political. He often came across as a bit of an asshole who was brusque with his girlfriend, Jo. Butterfield had lost touch with Haldeman but Jo and Butterfield’s wife, Charlotte, exchanged Christmas cards and snapshots of their children.

It wasn’t much to hang on to. But a fighter pilot knew about coincidence and chance, the quick maneuver in the air. It was the difference between ace or dead.

Haldeman! He tried to recall everything about him. How much could you learn from a double date and hanging around Fraternity Row? They had been in different fraternities. Haldeman was a Beta, which was considered the best. Old Harry Robbins, H.R. “Bob.” Butterfield needed an exit strategy and now he thought, “Here’s my out.” It was worth a try.

Butterfield had almost perfect Efficiency Reports, the formal evaluations that drive promotions. He had served as aide to two generals. With a gentle, relaxed charm he knew how to please the boss without fawning. He had earned early promotions, and his personnel file was stuffed with letters of commendation from top civilians at the Pentagon and from Vice President Hubert Humphrey. He looked the part of the classic Air Force officer. “He was drop-dead handsome,” said Charlotte in 2014, nearly 30 years after their divorce.

“If you’re going to get promoted to general officer,” Butterfield told me later, “you’ve got to be where the smoke is . . . in a really important, highly visible job in either Washington, D.C., or back in Vietnam. And command of a tactical fighter wing in Vietnam is what I wanted in the worst way.

“I was desperate to get back to Vietnam. If I have to be delayed [in Australia] for another two years, I’m dead in the water. I’m frantic, I’m actually frantic. I hate to admit that.” The urgency, he said, was simply because no one knew how long the war would last, and he did not want to miss out.

Butterfield awoke the next morning to heavy rain in New Guinea, and lay in bed thinking. If only he could talk with Haldeman, an unhurried session to tout his record: Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had employed him as a contact point in the White House. He had prepared McNamara’s regular military reports to the cabinet and accompanied him whenever he visited the White House. He knew a lot about power levers in Washington. He wanted to tell his UCLA pal about how crucial it was for him to be in an important, high-visibility assignment when he would became eligible for promotion to brigadier general, the one-star generalship, and the road to the smoke.

Would Haldeman understand? Could he possibly pull some strings? There were lots of strings to be pulled, especially from the vantage of the White House.

The weather stayed bad. Good. He wanted time. He grabbed the shuttle bus to the tiny airport terminal. Scanning the day-old paper from Sydney, he saw nothing about Nixon or his transition. Damn it! He thumbed through the other newspapers and several magazines. Nothing. At the counter, he sipped orange juice and coffee. The rain continued. Butterfield’s mind was churning hard. He bought an inexpensive bag of cookies and returned to the motel and hung the pidgin sign on the door: NO WAKIM MANISLIP (Do Not Disturb). Shedding his damp clothes, he put on a robe and sat to write. “Dear Bob . . .”

At first Butterfield wanted to describe his plight and see if Haldeman would intervene and assist with a new Air Force assignment. He wanted to get back to Vietnam with a wing command, a large unit of 75 or more planes. That seemed incredibly audacious. But Butterfield’s strong suit was personality. At UCLA he had been named the Most Collegiate Looking Male, and in high school the Most Popular. He had been class president twice in two different high schools, and student body president at the end of his junior year. He had earned letters and gold awards in football, basketball and track. Soon the letter to Haldeman was a direct appeal for a face-to-face meeting at the Pierre Hotel in New York, where the president-elect had set up his transition shop. Just 20 to 30 minutes. That was a bold request but Butterfield was a solid and respectable voice from the past.

He was running out of motel stationery, down to the last sheet. Going over to the bed, he lay down. What did he really want? Was it just an assist with a new assignment? Or was it more?

Butterfield imagined himself in an office talking to Haldeman. Would Bob still have that businesslike aura? The cold efficiency had doubtless appealed to Nixon. Butterfield knew the type from the Air Force. If he could get an audience, he would be able to establish a rapport. That was what he did, that was one of his talents. He knew that it was also dicey. If he went outside the chain of command to Haldeman, it could be seen as an impropriety. So he had to ask himself, What is my true objective? Why is it suddenly so important to put myself in front of Haldeman and try to impress him?

But in one of those rationalizations common to all and for which Butterfield forgave himself, he decided he could offer his professional services for a post on Nixon’s National Security Council staff. That would position him to return to Vietnam. That could be easy, he figured. He had to present himself as a clear-eyed colonel of excellent character and deportment. He was a graduate of the National War College, had a master’s degree in foreign affairs, had lived in six foreign countries. He pretty well knew the world and the issues. Not a bad package, he concluded. He was also combat ready and trained in every facet of tactical aviation—air-to-air, air-to-ground, air defense and reconnaissance. He was one of the few Air Force colonels with that range of experience. For two years, he also had been a member of the Air Force Skyblazers, America’s only formation aerobatic team in Europe.

Out of motel stationery, he went to the front desk and got more. Soon back in Australia, he revised his letter, making it into a biographical résumé, and sent it off. Later he tried to call Haldeman in New York. No luck.

Finally, Butterfield reached Larry Higby, Haldeman’s executive assistant, on the phone. Higby was Mr. Step-and-Fetch-It. (Later in the Nixon White House the staff assistants were called “Higbys.” Even Higby eventually had a Higby who was known as “Higby’s Higby.”)

“Colonel Butterfield, this is Larry Higby. Bob is busy now. Can I be helpful? Bob knows you’re calling and he told me you two knew each other at UCLA.”

Butterfield explained that he was coming to Washington on business. Of course the only business was to see Haldeman but he didn’t say that. He said he wanted no more than 30 minutes on an important personal matter. He knew he wasn’t fooling Higby, who replied they should talk the next day, and that he would probably have more to go on.

In Australia Butterfield was his own boss in charge of his schedule so he arranged to take leave and set up his travel. Within days he was in a room at the Washington Statler Hilton watching Nixon on television announce his cabinet.

Butterfield would later write in his memoir draft, “I took note of the Cabinet selectees’ names and as I did so a strange feeling came over me. It was one I’ve never forgotten—a good feeling, one of confidence, a premonition of sorts that I was closing in on my destiny, that I would definitely be a part of this upcoming Administration.”

The next morning, in freshly pressed uniform, Butterfield took a cab across the Potomac River to the Pentagon, which was familiar territory. He had worked there in several assignments. During the morning he tracked down colleagues who pulled the strings on the many military programs in Australia.

At noon he walked to the vast Pentagon Concourse, a mini-mall of retail stores, found a pay phone and called Higby.

“Mr. Higby is not available. Would you care to leave a message?”

Goddamnit! Butterfield muttered. He stared at the coin box of the pay phone, his long legs extended out of the booth. Now he was in the delicate minuet of making sure Haldeman knew he was available but not appearing overanxious. He calculated that if he called back in 30 minutes, and then again and again, his call slips could pile up and he would look like a pest. Not persistent, but annoying. Difficult and unwelcome. He decided to play a version of Hard to Get. He would wait until mid-afternoon to call again.

He went into D.C. and lunched alone at Duke Zeibert’s, then one of the most famous and busiest restaurants with the power set. He could think of many restaurants to have a belt—the Jockey Club, Rive Gauche, or Sans Souci. He’d dined and drunk in all of them. No city brought back more stirring memories because over the years he had been in and out of Washington, especially as the senior aide to General Rosy O’Donnell, who had been commander-in-chief of the Pacific Air Forces in the early 1960s.

At 3 p.m. he picked up the phone.

Bob will be able to see you tomorrow afternoon here in New York, Higby said. They agreed on 2 p.m.

The next day, Butterfield flew to New York City and checked his bags at the Plaza Hotel. As soon as the meeting with Haldeman was over, he was heading back to Australia. He then went down to the Oyster Bar for a light lunch and a little meditation—a comforting stream of hope punctuated with flashes of deep worry. He needed to present himself as a competent potential addition to Nixon’s team. There was much to think about. What exactly was the course he wanted to take? And was he going about it in the right way? How many acquaintances from decades back did Haldeman have knocking on his door? There was a bit of effrontery in it, but Haldeman also might find it comforting. The top aide to the president might be suspicious of new friends.

Butterfield stopped at the men’s room to gargle and brush his teeth, a ritual he practiced before important meetings. Soon he was out the door with briefcase in hand. It was cold but sunny, just right for the walk of several blocks to the Pierre, which had an elegance of its own. He visited the men’s room again to comb his hair. Whenever he went hatless, even in the slightest breeze, his wispy hair would go standing up on end. He was conscious of not wanting to look unkempt or goofy as though he had just stuck a finger in an electrical socket.

“I’m walking in for the final exam,” he recalled.

At the front desk, he asked for the main floor of the Nixon Transition Office and headed for the elevators.

Suddenly there was a commotion behind him, men moving fast. As he turned, he saw this wave sweeping in from the chilly air outside. He knew at once it was Secret Service moving with that special urgency and self-importance. “There’s this rush of humanity,” Butterfield recalled. “It looked like 40 or 50 people. Some of them had cameras. So this was the press. And lo and behold, Richard Nixon. I’d never laid eyes on Richard Nixon, but he comes rushing in. I’d thought at the time he looked a little more handsome than I thought he was, and a bit taller.”

Nixon smiled and nodded to the hotel staff and bystanders and did not turn Butterfield’s way. In 30 seconds Nixon and his Secret Service agents, and perhaps a handler or two, had crowded into an elevator and were gone.

Butterfield marveled at the way the old Haldeman connection was going, the timing, the prospect . . . the sense of destiny. In the back of his mind was the question: how far to push this? Well, he was pushing it to the limit, and the main event was to come. Maybe his hope was excessive, and he would get a polite brush-off, “Good to see you, Alex, and may the rest of your life turn out well.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (October 11, 2016)

- Length: 304 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501116452

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Last of the President's Men Trade Paperback 9781501116452

- Author Photo (jpg): Bob Woodward Lisa Berg(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit